On Saturday evening, at an event purportedly dedicated to celebrating the film industry’s “independent” spirit, Jeff Bezos’s Amazon was on the tip of many an emotional award-winner’s tongue. Only one awardee expressed some self-conscious discomfort at thanking a mega-corp (in that case, Disney); another moved herself to tears while describing how director and actors alike knelt down and helped pick set dressing up off the floor between takes, apparently a sign of anti-hierarchical humility and generosity. I thank god I am able to spend this Monday with James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s Still Film (2023), a return to the actual world of movies.

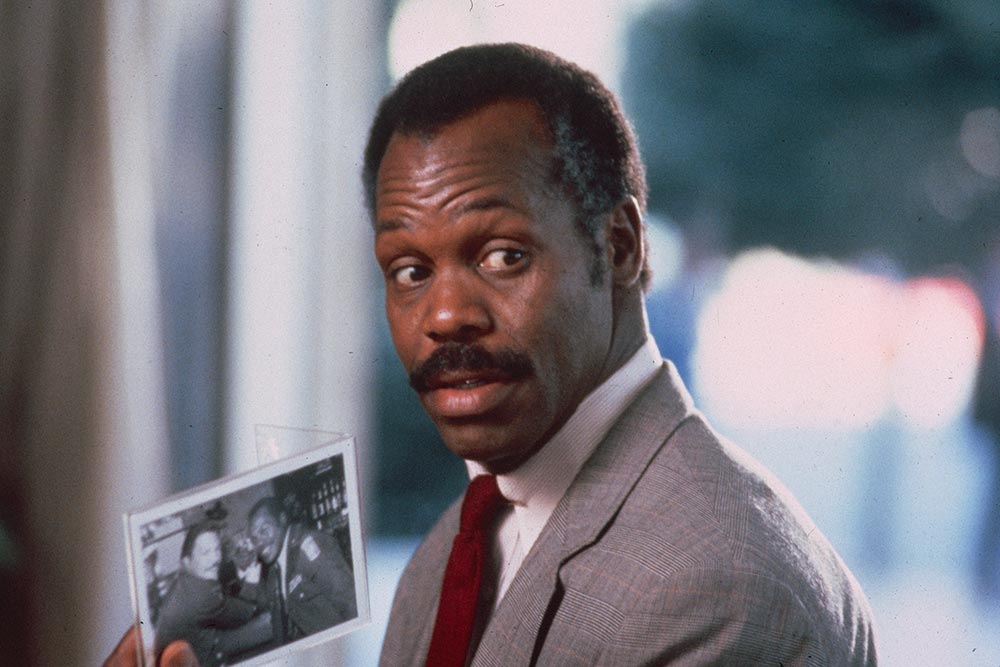

Still Film takes on, among many other things, the existential quest to know and define one’s self, as refracted through the fantasy space of cinema. Its visual track presents a series of 35mm publicity slides from Hollywood films, drawn from Kienitz Wilkins’s personal collection of studio press kits. All of the films represented were released between the year of his birth and 2000, when he turned 18. Some scratched, faded, and showing traces of their long journey to Kienitz Wilkins’s scanner, the staged on-set stills are presented in an associative order, used mostly for their dramatic and emotional rhymes. Concurrently, Still Film’s audio track is a dialogue-cum-interrogation between two lawyers, a recording technician, and a witness on the stand, all played by Kienitz Wilkins himself. The dialogue is delivered at a breakneck pace, unrelenting and overlapping, full of ums and uhs and post-commercial bumpers, as well as meta references to the recording process itself.

The script is deeply idiosyncratic, its tone a syncretic mashup between a trivia-laden HotMovieNews podcast riff, the wisecracking 1-2 patter of a film noir, the pablum of the trades, and a made-for-TV trial, scored by stylistically disparate music tracks from stock-licensing site Pond5.com. We see lots of Danny DeVito and Tom Hanks, and hear about KODAKCoin, Shutterstock, Drew Carey’s side hustle as a stock-footage photographer, former Mighty Ducks star Brock Pierce’s turn to cryptocurrency and American politics, the 2022 stabbing at the MoMA film desk, and the 2013 death of still photographer John Bramley while working on a Disney set. In many ways, Still Film feels like an update to James Benning’s American Dreams (Lost and Found) (1984), which surveys the soul of the U.S.A. through baseball cards, radio broadcasts, and the diaries of Arthur Bremer, the would-be assassin of George Wallace.

As the Witness is forced to sort through questions of authenticity—on the face of it, the case revolves around the intellectual property of a memory—he shuffles through the labor of the film industry, the conditions of movie distribution, and the development of film’s material formats, as well as Hollywood’s relationship to the human soul and its complicated role in shaping the development of the world around it. The Witness calls on his childhood memories and IMDb trivia in equal parts, defining industry terms as he tries to make himself legible in a garbled lingua franca of cinema and the corporate-cultural commentariat, litigating the promise and failure of moving images, specifically those of the end of the last century (“nostalgia is a liquid asset,” one of Kienitz Wilkins’s characters says).

A James N. Kienitz Wilkins film is always a deeply funny and fully humanistic reflection of the world as it unfolds in real time, and what it means to try to process that world through the tools of film- and videomaking. His work tackles bigger questions of selfhood, truth, and identity, but also drills into the material specifics of moving-image circulation, often returning to the predominance of DCP, the proprietary digital cinema package on which cinematic projection today relies (Indefinite Pitch, 2016, and Common Carrier, 2017). We are lucky that he works so consistently and prolifically, breaking down the falsehoods and afterimages of both documentary and fiction film, examining and interrogating each and every cog of the so-called “empathy machine” as it changes from year to year. Or, as much better put by his narrators in Still Film:

—Honestly, this whole racket . . .

—What racket? Life, law, movies?

— . . . feels neither here nor there.

Still Film screens tonight and tomorrow, March 6 and 7, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of Doc Fortnight 2023. Filmmaker James N. Kienitz Wilkins will be in attendance tonight for a Q&A.