Nearly a quarter century since it was submitted as a thesis project for his MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Christopher Harris’s still/here (2001) has emerged as an essential work of contemporary avant-garde and documentary cinema. In a creeping sixty minutes, the film captures the physical deterioration of traditionally working class African American neighborhoods in St. Louis, Missouri, and meditates on the myriad consequences of such long-term material neglect. From rupture and ruin, it unfolds as an audiovisual poem of sublime beauty and profound emotional depth.

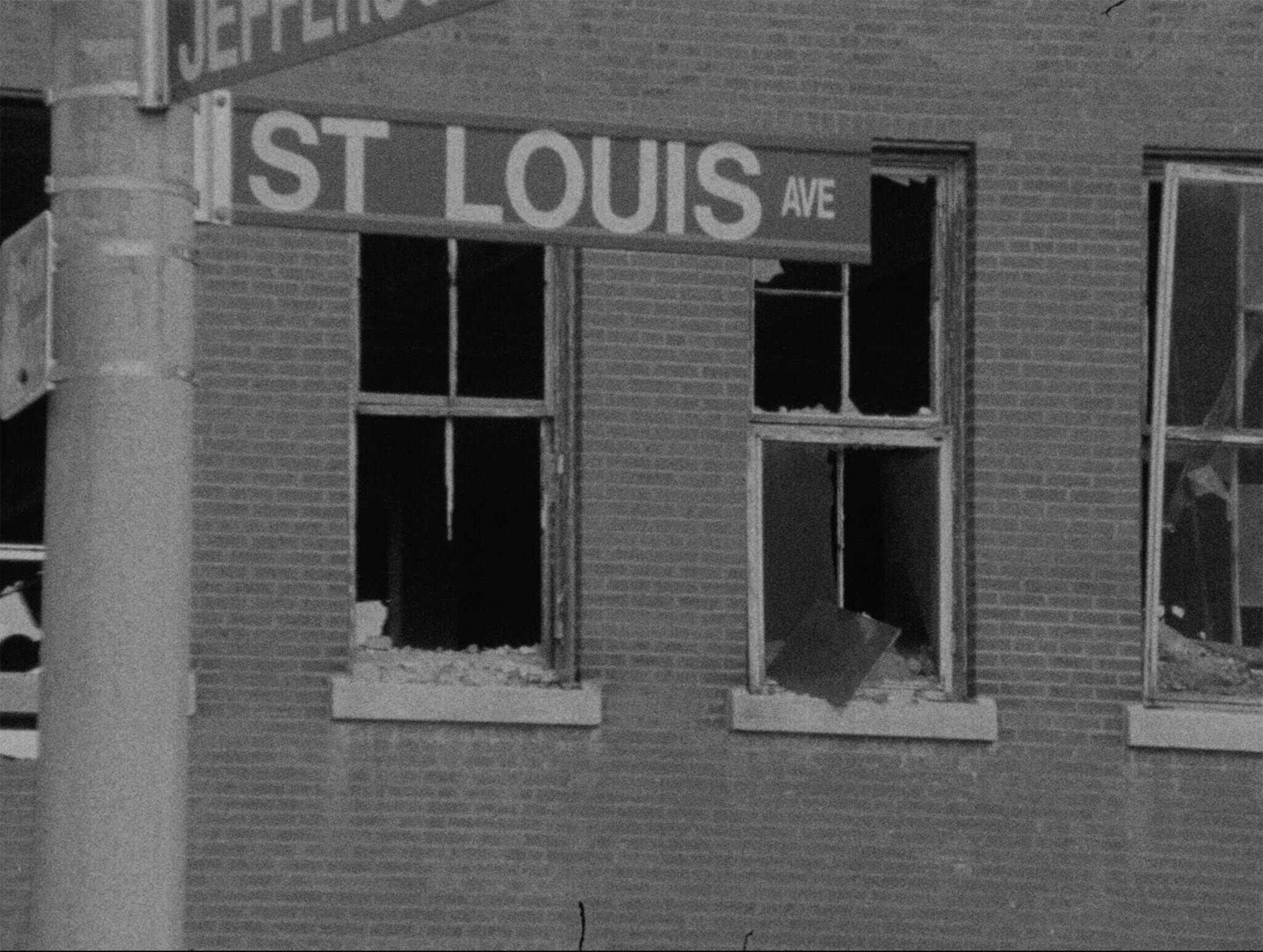

still/here contemplates the interstices of history, memory, blackness, and place through a formal structure that mirrors its content. Shot on black-and-white 16mm film stock, gritty images of dilapidated buildings appear aged and well-worn, yet hold steady in extended takes of deftly composed tableaux vivants. Harris foregrounds the tactile textures of his medium and format as light leaks, countdown leader, emulsion scratches, and analog grain populate the frames, making material the chipped and peeling paint, cracked, leaking ceilings, and rubble-littered lots that makeup the mise-en-scène. Such structural experimentation pulls back the curtain on the process and labor of filmmaking, a concept that also translates to architecture. For every misplaced brick in the film, Harris reminds us that there was once a human hand that laid it. Embracing stasis as a means for reflection, form as proxy for subject, and ruins as objects of reverence, still/here’s emphasis on the weight of past labor becomes heavier, ironically, as its fruits grow rotten.

A melancholic tension develops through the juxtaposition of the wilting visual plane of North St. Louis, where Harris was born and raised. Alongside raw materiality and slow duration, still/here loops and layers intricate sound design against abandoned urban sites for ghostly effects. Amid tattered interiors, the disembodied sounds of dishes clanking, doorbells chiming, footsteps wandering, and a telephone ringing suffuse the vacated spaces with the kinds of quotidian routines that often go unnoticed, but which, in their absence, leave a palpable imprint. Though the systemic erasure behind the states of decay is suggested, at one point, through a repetitious, automated message from the St. Louis Housing Authority, still/here more often sidesteps social prognosis. Leaving the aftermath of redlining and redevelopment implicit, Harris conjures the past in mourning, offering his film as an elegy for a locale that is inseparable from lives lived.

A key piece of cultural geography that haunts still/here is the cinema. Shots of the decrepit New Criterion Theater represent the most specifically defined space in the entire film. Whereas other locations lack an establishing shot to orient viewers, Harris spotlights the Criterion’s old school, fractured marquee in an early wide shot, and returns to the theater frequently thereafter. In an especially memorable composition, he fixes his camera behind a row of empty theater seats and toward a massive opening where an inner wall once stood. As sunlight sears inside to overexpose a significant portion of the frame, the gaping hole unmistakably takes the form of a screen. The scene is filled with the ambient sounds of the outside, urban environment, yet, as it lingers, one can almost hear lively pre-show chatter quieting before a projector starts to hum. The Criterion, a historically segregated Black theater, serves as a reminder of racial inequality, but also evokes a space that may have offered collectivity and respite for its patrons. still/here’s formal rigor and pervasive sense of loss prompt such nuanced considerations, and in the process, preserves these neglected structures as much more than the sum of their crumbling parts.

still/here screens this evening, September 20, at The Whitney Museum of American Art as part of “Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing.”