I would trade all the Hitchcocks, Fords, and Sirks in the world for one scene of Vincente Minnelli dreamers, being, walking as if they were dancing, talking as if they were singing, melting and solidifying between close-up and long-shot as an intricate bustle of extras and tea-cups teem around them. And if there is one film institution which is a staunch proponent for the Minnellian, and which is willing to trot out on four horses for this apocalyptic preference, it is the Stanford Theatre.

The Stanford is dedicating the whole summer of 2024 to showing nothing but Minnelli’s pictures. Take this opportunity to see them all. They die on the small screen, especially his later-period CinemaScope masterpieces Two Weeks in Another Town (1962), The Reluctant Debutante (1958), Lust for Life (1956), Bells Are Ringing (1960), and a host of others. But especially check out the rarest offering of all: Minnelli’s devastating 30-minute fantasy romance “Mademoiselle” in the MGM anthology film The Story of Three Loves (1953).

Minnelli shot it in a breezy 3 weeks and, according to his autobiography, he didn’t think much of it in retrospect. Makes sense, seeing as he marched quickly on to make his perfect Band Wagon (1953) and Long, Long Trailer (1954; playing with Story). But, Minnelli, working on autopilot, accidentally ended up making the manifesto for his cinema of melancholic dreams. The thesis: though soft dreams are a delight, remember: they last for a proverbial night (or a fortnight, or a lifetime); don’t be too teary when dreams end; the art of loving’s not too hard to master, and we build from there.

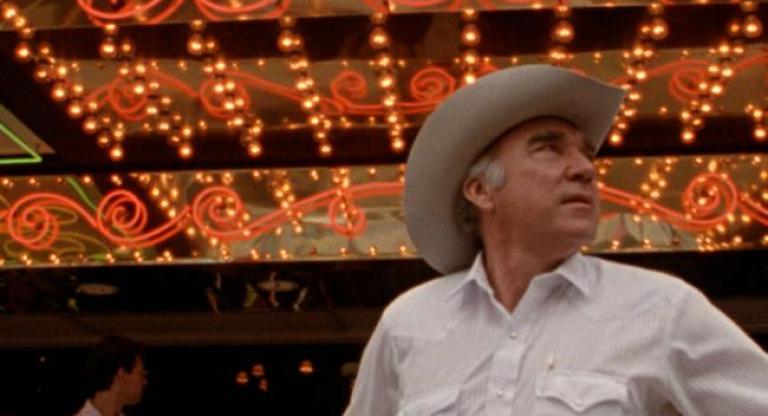

We’re in Rome. A fake Rome, yes, but a Rome of ruins and former glories: busted columns, broken busts, and stale villa bed-chambers in which kids like a 13-year-old Ricky Nelson are imprisoned by their parents. Little Ricky is annoyed by his 22-year-old governess, Leslie Caron (the future Gigi). She, a starry-eyed romantic, wants to read French poetry to him and inculcate him with a love of the word; he, not being the literate book-pilled sort, wants to do Boy Things. Go be a boy, then, Rick! Play in a Roman garden with a stick, you miserable little wretch. Rome’s wasted on you. For now. For in the stick-filled, ruinous garden, Minnelli commandeth that Young Rick shall happen upon, miracle of miracles, a witch: Ethel Barrymore. Minnelli has Ethel tell Young Rick she can grant him what he wants: to be a Man, to be old and done with his Governesses and Rules. Wish granted. For one night, and one night only, Young Rick is suddenly the dashing 28-year-old Farley Granger. And, wouldn’t you know it, Farley falls for Mademoiselle Caron.

I shan’t reveal how Minnelli resolves this Freudian pickle. Just know that the climax revolves around a sad dreamer who decides to speak in the language of their beloved, however alien the language, however little he knows of the beloved yet: Mais je vous aime! Je vous aime bien, mademoiselle! If you’re attuned to Minnelli’s wavelength, the only proper response is to weep at this shocking verbal eruption. Love is making the effort to speak in the other’s tongue, even if you make a bungle of it. Here, we’ve the anguish of feeling anything for anybody: Minnelli knew well the territory of dream, the terror of love, how fragile it all is. Minnelli’s oeuvre is it for me. His is as loopy, sensitive, kaleidoscopic, and, yes, beautiful a body of work as can be mustered from a perverse industry like Hollywood. Socrates was right: the best poets were those who knew how to compose a comedy as well as a tragedy. Through and through, this was Minnelli, the window-dresser from Chicago.

The Story of the Three Loves screens in a double feature with The Long, Long Trailer, on July 4 and July 5, at the Stanford Theatre as part of the series “Directed by Vincente Minelli.”