Cinephilia is not nearly the incisive, ceaseless, ever-peripatetic lifestyle we like to imagine; more often it is impatient, inattentive, perfidious. Ask the man who’d self-finance films to the exact scale of his desire rather than the tune of whatever’s been expected from him for decades. The months-long debate surrounding Megalopolis (2024) achieved exactly one thing: confirming whatever image (saint, sinner, renegade, fool) you have of Francis Ford Coppola. Perhaps it was too much to ask those reams and reams of spilled ink might find a few words on one of cinema’s greatest self-rejuvenations: three personally funded features that retooled the styles and themes of Coppola’s career with a freedom his New Hollywood contemporaries would never dare as their budgets ballooned and award campaigns churned.

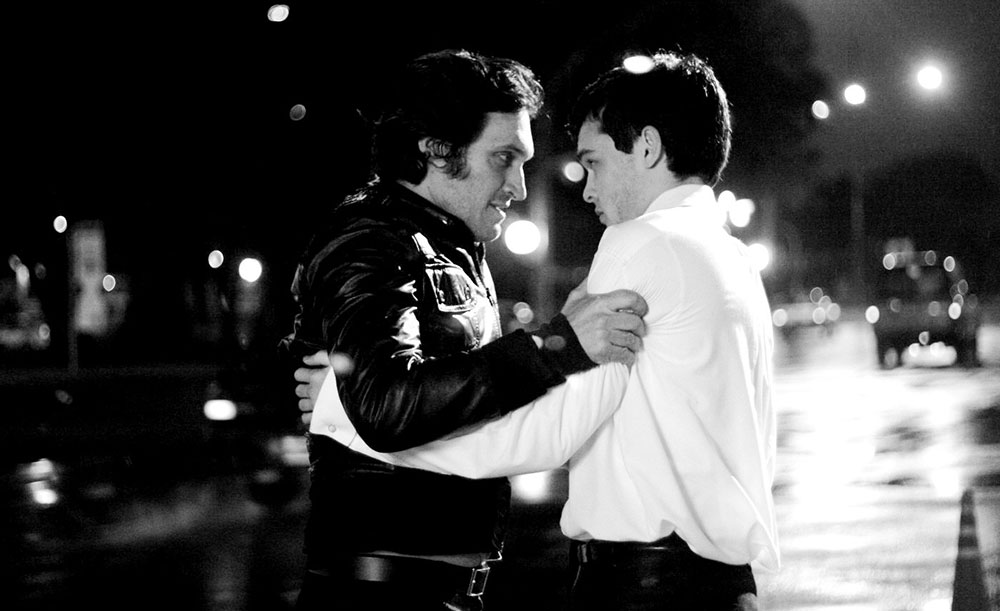

With respect to the positively Ruizian beauty of 2007’s Youth Without Youth or gloriously gonzo self-portrait that was 2011’s Twixt, this era’s crown jewel is clearly Tetro—a film Coppola began writing at age 17, found again nearing 70, and by 2009 finished with decades’ perspective. That’s not to suggest a film venting bitterness and elegy, regret or rue. However wisely it explores those mindsets, Tetro is also among the freest-feeling works in Coppola’s corpus, staging an uncertain reunion between brothers (Alden Ehrenreich, baby-faced; Vincent Gallo, visage anything but) for formal play and personal musing. Though images trend classical—shots are tightly locked, often at admirable length—cuts play loose, bearing a sense of motion between shots, in their ability to establish new set-ups and perspectives across a continuous space, one might call limber-limbed. As flashes of color come packaged with ersatz gestures (compressed aspect ratios, theatrical fantasies) Tetro vacillates between dreamy past and frozen present.

Nearly every Coppola film runs autobiographical—either some expression of his personal trials or, to invoke Jacques Rivette, a documentary of its own making. Tetro, started and finished over the span of 50-plus years, constitutes cine-memoir in extremis. Why was a 17-year-old theater arts major—whose father, himself a composer, disapproved of his vocation—compelled to begin drafting this story of a young man living in the shadow of his composer father? We can guess. But what drew Coppola back to the material when it was personally practical (and financially logical) to stay on his vineyard? While Tetro’s narrative secrets unfold like a noir befitting its black-and-white images, larger significance remains oddly obfuscated. I’ll cease my words and seek wisdom in Coppola’s own: “Nothing in it happened, but it’s all true.”

Tetro screens this evening, October 17, and on October 19, at the Roxy as part the series “Ace Theater Presents.