Stepping out from an "insane show" unfolding above him in the "multimedia, multilevel, gallery, consortium, collective" he's called home for decades, Bay-area filmmaker/archivist/programmer/educator Craig Baldwin recently spoke with Screen Slate via telephone while packing his kit for a weeklong tour of New York, which will include a retrospective at Metrograph, an evening at Light Industry, and a series of tributes, a curated program and a live performance, all at UnionDocs. For 90 glorious minutes he breathlessly discussed celluloid, performance, regional film cultures, and the purpose of archives, while answering questions I hadn't even thought of and unspooling connections that didn't make sense until the following morning. He made sure to pack his splicer. Be ready, a freak wind is blowing eastward.

Baldwin's conversation and films are both rejuvenating fields of colliding atoms. Within his maelstrom, words and images slough their grammatical confines and synthesize new possibilities and directions. If contemporary screen culture is plagued by cannibalistic sequels and remakes, the work of Baldwin and other archival filmmakers represents an ecological counterweight to Hollywood's resource-draining profligacy. The atomic particles of his films are liberated shards of "orphan" films discarded by various institutions. For years he has saved these reels, amassing a frenzied archive. By "salvaging and redeeming these orphans… the idea is that marginalized people could collect these films… [and] they would actually make a difference because people actually use them." To that end, he shares with fellow archivist Rick Prelinger the idea that "the archive is for use. It's not just for preservation." This access grants filmmakers and audiences the opportunity to "claim something that we own, which is film history." This "genre, lifestyle, sensibility" he calls "Orphan Morphin'."

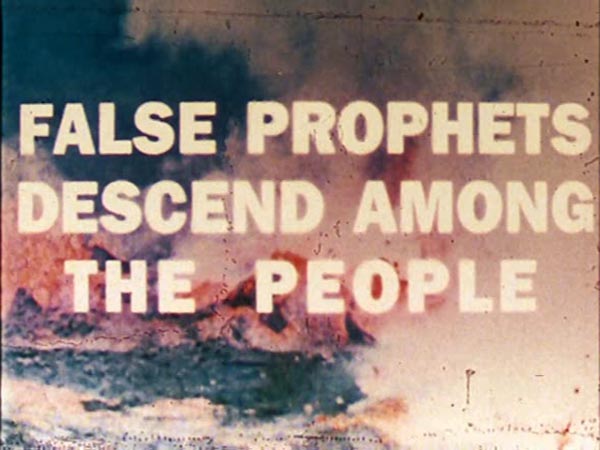

The orphans have yielded treasure ranging from Hollywood melodramas to MST3K-worthy sex-ed shorts, which Baldwin amalgamates (often with footage he shot himself) to tell both true and would-be American histories involving natural bedfellows the C.I.A., Scientology, aliens, copyright litigators and the corporate media. Calls to mind Burroughs and Debord? Baldwin has been working on a feature concerning the very same. During his New York stay, Metrograph will host Baldwin for a two-day retrospective featuring a selection of recent 16mm remixes as well as Baldwin's shorts ¡O No Coronado! (1992) and Wild Gunman (1978) and the four features for which he's best known: Spectres of the Spectrum (1999), Mock Up on Mu (2008), Sonic Outlaws (1995) and Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1992). (All showing on 16mm except for Mu.)

Preserving a "radical subjectivity" and and maintaining a foothold in San Francisco have compelled Baldwin to shift his focus from found-footage narrative features to an "expanded cinema," which he'll bring to UnionDocs on Saturday, March 2 in the form of a performance featuring two projectors mounted on lazy susans spinning before an audience wearing 3D glasses.

"I think that's what's more appropriate for me at this point in my life," he says. I'm totally impoverished, and I can't get people to shoot a film, and what I'm doing is using the material I have" to create "very analog, very tactile beautiful machine art." The results are sweaty, intimate happenings: "Because of the scale, which is so humble and first-person and embodied by some guy between two projectors...there's an honesty that you see in performance art."

Baldwin continues, "We can enjoy the physicality of [the performance] and the rudimentary elementary feel of it that's primitive and analog and tactile. That's what my thing has become. I can still tell stories, but I'm a little shy of that right now. The narrative is overflowing in the found footage. It's invented there. My thing is more puncturing of a scenario or vignette and letting the meaning overwhelm you."

The performances reflect an "in situ, lived-in experience" and "sculptural quality" that Baldwin sees coalescing among San Francisco's 16mm set. The medium presents a low-budget, low-fi outlet for Baldwin-filmmaker while Baldwin-programmer and Baldwin-educator struggle to keep a roof over him, the archive, the studio and the gallery. "While I hope to remain a working artist… I'm totally compromised by the insane situation I'm under here, maintaining a tiny little wedge in an area that's rapidly gentrifying." If there's hope for San Francisco, it's somewhere on 16mm film in Craig Baldwin's archive.

Despite the financial hardships, Baldwin is steadfast in his self-imposed marginalization as a "punk-carnival type of guy." He has fashioned a resourceful cinema with commensurate righteousness between production and product. His pivot toward performance establishes community and extends the reach of his archive, while preserving his dialectical vision. "I see my level, which is underground. It offers more personal experiences.... [audiences and artists] experience an embodied idea where everybody looks at each other and recognizes each other at the pre-show or intermission."