The short documentaries of Tony Ganz and Rhody Streeter, which have been newly restored thanks to Jake Perlin and The Film Desk, offer a wry and biting view of the United States in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Their preternaturally well-chosen subjects are often crystalline clear sites of American conformity and materialism—a retirement community, a hotel for newlyweds, the Muzak corporation, and the Campus Crusaders for Christ, just to name a few. Using interviews and a deceptively straightforward camera language, their films bring the dark underbelly of the American dream into sharp focus in both hilarious and tragic ways, conjuring Sinclair Lewis by way of Devo or Jello Biafra.

The duo's work appeared under the auspices of the journalist and filmmaker Jack Willis’s satirical variety program The Great American Dream Machine (1971) and later The 51st State (1972 - 1976), an experimental news program that aired locally in the New York area. Acting as interstices between news segments, their films provided potent dispatches from around the country, cut with brilliantly sly counterculture sensibilities. In many instances, the subjects speak for themselves, and in this way, Streeter and Ganz’s work prefigures cinematic critiques of American life to come from the likes of Errol Morris, Michael Moore, and beyond.

Ganz and Streeter graciously took the time to speak with me on the occasion of Anthology Film Archives’ series “America—Everything You’ve Ever Dreamed Of.” During our conversation, we discussed everything from how they approach their subjects, to the power of youthful naïveté, and how to find bathing suits in the Poconos in October.

Chris Shields: How did you two start making films together?

Rhody Streeter: We both met at Harvard. I had dropped out for two and a half years, and got into the film editor's union at the lowest level, a sweep the floors kind of thing. I'd been a child actor and I'd done some horror films. I was a body, I was a boom man, I helped build the set. I mean, it was all very cheap films. In fact, one film ended up on that show where the two little puppets make these smart ass comments.

CS: Mystery Science Theater?

RS: Yes. I think it was The Horror of Party Beach [1964].

CS: Oh, Del Tenney. I'm a huge fan. It's a great film.

RS: I went back to Harvard and said I'll do my freshman year over again. Tony and I met in a freshman seminar and it was run by…

Tony Ganz: Robert Gardner and Stanley Cavell, who was the smartest man in America [Laughs]. And Robert Gardner was, you know, probably in third place. It was a small group of people, it was a film seminar. I was in shock at how high the level at which this discourse between them and ourselves was conducted.

I had a roommate from the Tongan Islands. He invited me to come back to Tonga with him one summer. Rhody and I talked about it, and we went to Gardner. And he said, “I'll give you some raw, raw stock and a Bolex,” because it had occurred to us that maybe we could make our own Dead Birds [1963]. Well, we didn't exactly do that, but we did make a 20-minute film. I don't know that we can actually qualify it as an ethnographic film, but it was our sophomore attempt at doing such a thing. That really cemented our friendship.

RS: When we were there they built a little grass hut for us—a little room—and we slept under a tapa cloth. I don't even know how many nights we were there, but we shot with the Bolex.

TG: I think we shot ‘til we ran out of film.

CS: Hoi—Village Life in Tonga [1967 - 1969] is purely observational and has an ethnographic dimension, but all the other work in the Anthology series moves into this very funny, biting, and dark vision of American capitalism and conformity. I'm thinking of the Sun City film, The Best of Your Life [1971]. How did that one come about?

TG: I graduated. Rhody went off to some Marxist commune in Illinois or something. (I'm exaggerating only slightly.) I was teaching school in New York and I read an article about Sun City.

RS: I was heading out to the West coast, sort of to Portland, Seattle, somewhere there to do a collective commune kind of thing. So, Tony calls me and because of Tony's chutzpah and energy and contacts and all that...

TG: Well, I knew Jack Willis.

RS: He was a mensch.

TG: He was a mensch. He had started The Great American Dream Machine, it was just getting off the ground at WNET. I went to him and said, “Listen, all I can offer is that my partner and I will work for nothing. We won't let you down.” One of those, you know, throwing yourself on the mercy of the court kind of 22-year-old speeches.

I said, “If you think, as we do, that Sun City has a kind of sardonic quality that makes sense for The Great American Dream Machine, just get us there and you'll never have to speak to me again if what we come back with is unusable.”

Jack said, “That’s fantastic.” He had that same kind of sensibility. We thought, we’ll go out to Sun City, we'll shoot some B-roll, we'll put something together, and it'll be old people waiting at the anteroom before heaven or whatever.

RS: So, Tony and I went out there and arrived with a Bolex and a tape recorder, and then we started talking to people. I remember Tony and I driving out to the desert, which of course is only right there, 20 feet away and falling out of the car. Hysterical. And it was like, “What are we gonna do?”

TG: I think we thought our careers were ending before they began [Laughs].

RS: Tony called Jack and said, “We gotta shoot sync sound, we gotta do some interviews.”

TG: Gotta hear people talk. So, we went to LA and we rented an Eclair. We didn't exactly know what we were doing, but we figured out how to thread the magazines in the black bag and we shot it.

CS: I think it’s such an essential part of the film that these people speak for themselves. The brochure comes to life but there is, like you said, this sardonic aspect to it that kind of carries through the rest of your work. I'm really interested in you two as collaborators. Your subjects seem so well chosen, they communicate something more about America. How explicit were your conversations?

TG: I honestly think, in a retrospective sense, that it all works together in ways that suggest a kind of programmatic approach, which I don't think we had. We were pretty young. We responded with a sense of immediacy to a given idea. We reacted, especially with The 51st State films, which are five out of the eight or nine [in the program], to ideas sort of as we stumbled across them.

RS: With The 51st State films, they said, “We'll give you a contract for 50 minutes.” They didn't say exactly, but they were expecting each film to be around five minutes. We were the commercials. I mean, we were the leavening, we were the contrast for the news. I don’t know if you know anything about The 51st State, but it was an experimental program for WNET in New York.

TG: It was also Jack Willis. I think he was heartbroken when Dream Machine ended. Then he said, well, let's do this again, and we'll make it a news show unlike any other news show. And, it'll be about New York and nothing else. I think we fit beautifully into that slot.

RS: The way we tried to make the films was with a sort of underlying sense of humor. It wasn't, of course, jokey in any way. It had more to do with the seriousness of these particular subjects, they suggested a narrative approach that was easy enough for us to follow. I think we had to do a lot of editorial work though.

TG: We shot them quickly and then cut them slowly. It’s not as if we had a pre-formed sense of identity as filmmakers. I do think we were both very concerned and we talked a lot in the editing room about the thing you said a minute ago, that people needed to speak for themselves. We didn't want to skewer people. We didn't want to make fun of people. We really had a very sympathetic view of these characters.

RS: I think we were appalled. I mean, this is like, you know, ‘68, the assassinations and all that. We definitely had a New York sensibility and were kind of appalled at this in a way. And so, in some weird way, we're outsiders looking in at this other part of America, and kind of gobsmacked a little bit about what's going on.

TG: This whole conversation started with this sardonic critique of American culture. It was easy enough for us because it just matched our bond with each other, our sense of humor, and all of that. We were exactly the right age for that sort of thing. If we could have made a few more films as corollary films to the Men’s Shelter [1973] film, we would've loved to do that. Which brings us back to Jack Willis in a sense. You know, if we could have been the Maysles, or Jack Willis.

CS: I see that with the more vérité driven films in the program like Men’s Shelter and the Hoi film. It's nice that the program opens with the Best of Your Life [1971], but then it ends with A Trip Through the Brooks Home [1971-1973] because you get two formal versions of the same subject.

TG: There’s only like 20 seconds of narration in all our work. I have to admit, and especially seen here, it has an attitude. And I can't pretend that—“Oh no, we were just flies on the wall.” I mean, we were, we had a couple of times when we really tipped our hand. And Rhody, should we talk about, in the Best of Your Life, the little cut that PBS made?

CS: When they’re basically sieg heiling while they're doing yoga? I was profoundly tickled by that.

RS: [Laughs] Yes. I think we were very lucky for a number of reasons. One, we were kind of ingénues. We were kind of like, let's go for it. I think, in some ways, we did not carry ourselves with much pretense. I think that was part of our charm. Who are these dudes here? These kids?

TG: Well, I think we were quite disarming in exactly the way that Rhody said, in an unintended but not strategically thought out way.

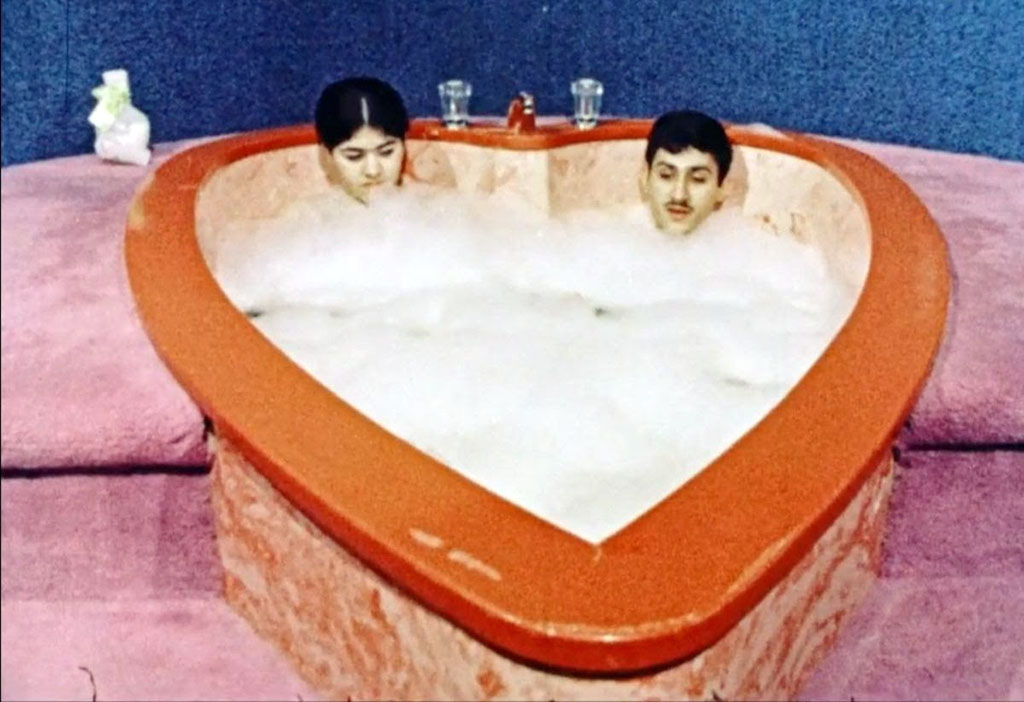

CS: In Honeymoon Hotel [1971], I thought, how did they get these seemingly conservative people to sit in the hot tub and talk to them?

RS: I think it was probably October or something like that. Tony went to the head of Cove Haven, and he said, “You know, if we don't get people in the bathtubs, you got nothing.” So, at some point Bernie says, “Bernie was just the entertainment, the piano guy, we’ll tell the couples we’ll give you a free weekend here on your one year anniversary if you let these dudes here come and film you in a bathtub.” But then we had to supply bathing suits, and we had to go find bathing suits somewhere in the Poconos in October.

CS: And then, of course, there’s that final shot of Bernie playing piano where you hold on his face just a moment too long. Your work, to me, prefigures a lot that's happened since. I was thinking of something like Gates of Heaven [1978] where you hold it just long enough that the veneer of what you see starts to betray itself.

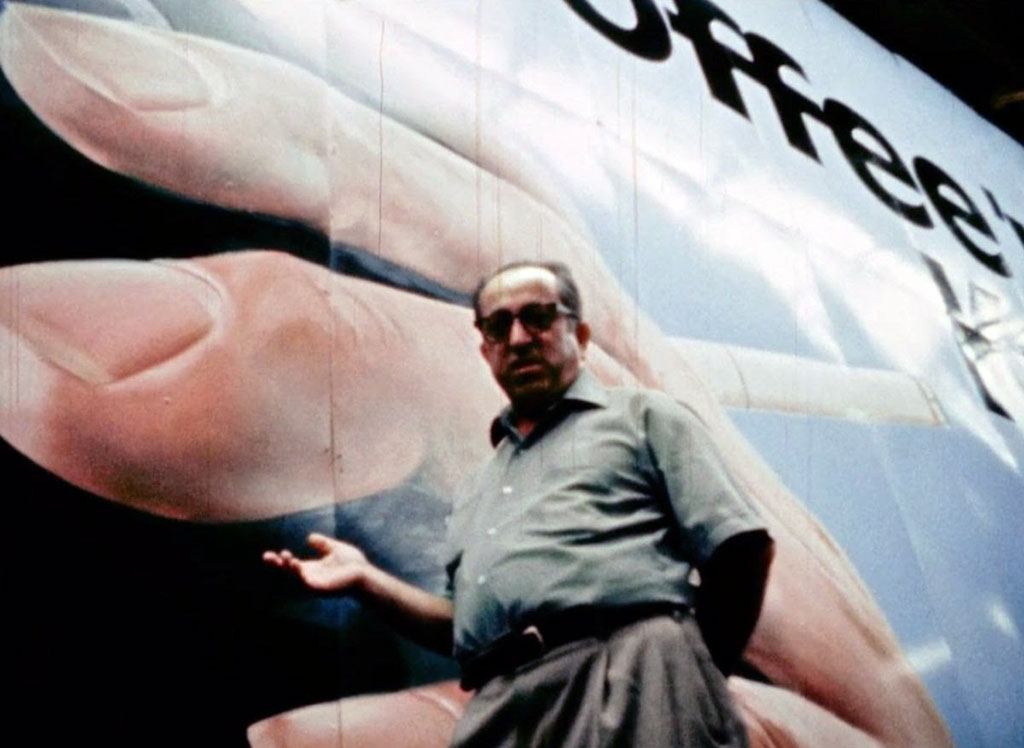

TG: I don't know whether this is in our defense or whatever, but this idea that we've sort of been suggesting to you that we just sort of stumbled across things, in some instances we actually did some work to arrive at these subjects. I don't remember who was shooting when we did that slow push into Bernie and then held on him for 15 seconds. But that consciously suggests a darker point-of-view that had clearly not eluded us in terms of the possibilities Honeymoon Hotel presented. But conversely, we both also love the Sign Painters [1972] film because…

RS: Because they're just real guys!

TG:. And there's no under-the-water-line sense of what's going on.

RS: If it doesn’t look like a turkey it’s not a turkey. [Laughs]

CS: That film is great because it shows this really anti-intellectual and direct relationship to art, to painting. In a way, it feels like an old master’s studio, but also like a mechanic’s shop. It’s mid-century working class guys. It's Ralph Kramden but he's painting.

TG: It's Ralph Kramden meets Lichtenstein.

CS: Again, it’s that sense of humor and sympathy. It’s really honest work.

RS: Gardner pointed out there is an arc to our work and I think it's like in Men’s Shelter. We absolutely love the doctor and the guy that says, “I just wanna be out in the street, get drunk,” And the doctor says “Even though you'll break more bones?” But the guy says, “And you'll fix me up,” and then he winks at the camera. It’s like these two, they're just very much who they are in the most beautiful way. In a weird way.

America—Everything You’ve Ever Dreamed Of: The Films of Tony Ganz & Rhody Streeter runs June 21-27 at Anthology Film Archives. Rhody Streeter and Tony Ganz will be in attendance for a Q&A following Friday and Saturday’s screenings.