From the outset of American filmmaking, storytellers have turned to the western as an imperfect reflecting pool of our best – and worst – tendencies. However enduring, these classic portrayals of gallant gunslingers and mustache-twirling stagecoach bandits have eclipsed a nuanced history. The years following the Civil War saw droves of emancipated Black Americans riding west alongside Rebel and Yankee veterans. For the formerly enslaved, settling beyond the Mississippi offered opportunities for land ownership, higher pay, and relative mobility. Yet while the on-screen presence of Black performers is as old as the Horse Opera itself, it took a shocking 80 years before cinema saw fit to crown these stars with the same idolatry of their white counterparts.

Early examples, like the 1939 Herb Jeffries vehicle Harlem Rides the Range, fit squarely within a history of “race films” created for a segregated theater-going public. But the one-two punch of a post-War Civil Rights movement and Hollywood studios’ waning stranglehold ushered in an influential, albeit brief era. Like their progenitors in the American West, the emerging Blaxploitation genre offered heretofore unheard of avenues for Black filmmakers. These films included a wide array of social dramas, revenge fantasies, and wry comedies that centered Black characters as complex protagonists of their own stories.

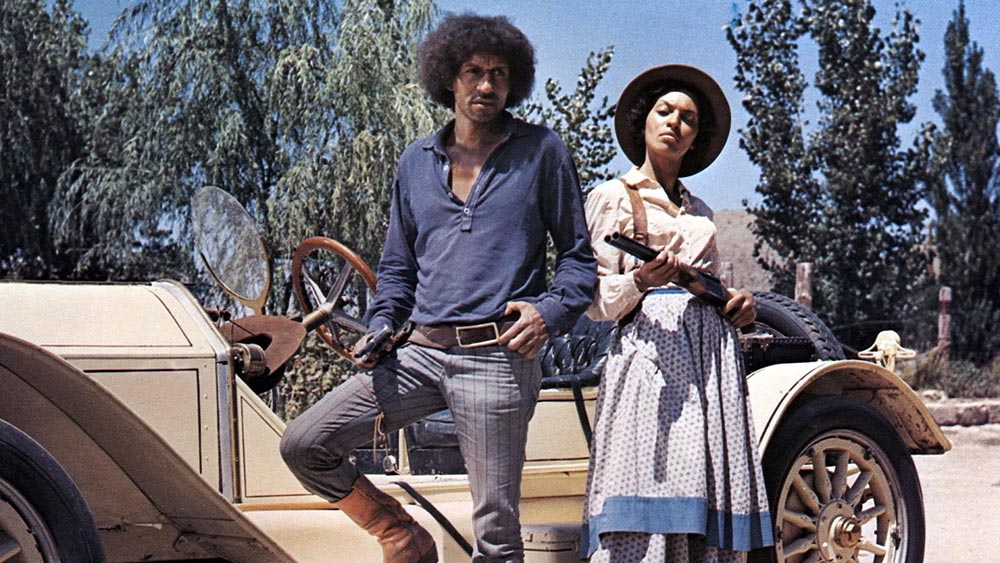

Starring established leading lady Vonetta McGee, and written by her then-partner and co-star Max Julien, Gordon Parks Jr.’s 1974 western Thomasine and Bushrod shifts these heroes from post-Reconstruction to the early 20th century. Shut out from the era’s accelerating prosperity, Thomasine and Bushrod turn from bounty hunting to bank robbing, redistributing their spoils among the dispossessed like latter-day Robin Hoods. To stay step ahead of the law, the lovers have no choice but to navigate a landmine of ever-present white violence. Even the “good ones” regard the pair with naked condescension, referring to them as “children,” “honey,” “boy,” and other unmentionable insults. After their first bold heist, a local photographer gives her testimony with genuine shock: “Negroes don’t rob banks,” she exclaims, “they dance and sing and steal chickens.”

Released, ironically enough, the same year as classic “you-couldn’t-make-this-today” satire Blazing Saddles, the younger Parks’s second film elevated the tropes of a lovers-on-the-run story into new territory. The result is a call for resistance and autonomy that finds a timely story in our overlooked past. The legend of Thomasine and Bushrod contains more than a few familiar plot twists, but the philosophy at its core is a timeless one. For Black heroes who refuse to toe the line, the stakes are higher – both material and deeply personal. Confined to a belligerent social structure, they must answer this degradation with a bold approach: take whatever you want, however you can, with the strength of your own power.

Thomasine & Bushrod is on Criterion, Pluto, Prime, and Tubi