Our dispatch on the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival comes courtesy of Mark Asch, Elissa Suh, and Maxwell Paparella, who offer their impressions of this year’s program, the state of cinema and criticism, and Hogtown itself.

Mark Asch

Eduardo Williams’s The Human Surge 3 jumps across the world with practically each cut, taking in locations from Sri Lanka to Peru, in which young subjects wander restlessly across towns, through forests, into swimming holes. Shooting with a wide-angle lens, Williams follows the people in his film as they move through the world—or sometimes his attention jumps to another group within the same location, or to a conversation within the same group, like a guest making the rounds at a party, rendering the film’s already incidental dialogue almost exquisite corpse–like. Where Williams's previous The Human Surge used globetrotting Global South locations and a distractible, distorting camera to place itself within the buggy backend of the global economy, The Human Surge 3 (there is no Human Surge 2) is more tender, often simply spending time with appealing young people immersed in water. At once disorienting and amiable, marked by jumpy sudden cuts and long-take loungers, the film evokes digitally diasporic social life, with heterogeneous friendships as wormholes, traveling from phone to phone amid a jumble of different contexts. The film ends with a sequence shot with a 360-degree camera that looks like what happens when you accidentally switch from photo to panorama mode, bringing a geographically mixed selection of the cast together in the same location and the same impossible frame. They walk up a hill, grouping and regrouping at different points along the way, all together on a lovely pilgrimage to nowhere, in a sequence that I took as an allegory for what it's like to come to the Toronto International Film Festival every year and see all my foreign friends from the group chat.

Anticipation for Toronto this time around came tinged with a blush of the apocalyptic. It was announced last month that TIFF’s title sponsor, the Canadian telecom giant Bell, would end its partnership with the festival later this year, leaving an impending seven-figure shortfall and the prospect of next year’s pre-roll featuring an advertisement for an even less palatable company (maybe even less than Therme, the Austrian developer of a water park and spa planned for the island park Ontario Place, who had announced a decade-long partnership with TIFF “promoting the role of art and film in creating more human cities” before the festival pulled out, following a pressure campaign).The ongoing SAG strike left many actors unable to attend the festival to support the kind of “one for them, one for me” wistful script-led adult dramas which reliably draw the middle-class, middle-aged, middlebrow audiences more or less keeping arthouse moviegoing alive—always a necessary programming strand at TIFF, the most public-facing of the world’s major film festivals.

No one lives in Park City or Telluride or Cannes or Venice now that Airbnb has priced out even the hospitality workers, but Toronto is a real city and we visiting fest-circuit critics attend screenings alongside its very real denizens. While it’s possible to chart a course through the program seeing mostly more experimental fare like The Human Surge 3, TIFF is all things to all people, including Toronto’s significant Chinese community. (Chinatown is close enough to the festival zone to walk to for a group dinner, perhaps with Eduardo Williams tailing behind with a fisheye camera.)

One actor who is certainly not on strike is the Hong Kong megastar Andy Lau, a guest of honor at the festival whose career-spanning talk was expectedly bland, though I enjoyed observing his show of concentration when turning to the screen for clips from Boat People (1982) and Running Out of Time (1999), his easeful smiling stillness when half-listening to his words translated into English, his cheery thumbs-up one-liners—in a word, his stardom.

Lau is an actor whose work has meant an awful lot to me over the years, but though I’ve been aware of his stardom any non-Western performer is necessarily going to seem like a niche interest. Days of Being Wild (1990) rides the charisma of several generation-defining performers who could nevertheless walk down most streets north of Canal without being recognized. But seeing Lau accept the love of a crowd and hold it lightly in the palm of his hand, feeling them laugh and sigh as he spoke, hearing what I assume is Cantonese for “This is more a comment than a question” during the Q&A, seeing the homemade signs and banners held up by audience members, seeing them rush the stage at the end, pushing past each other to hold up magazines to sign or gifts to give (including, bizarrely, a white cowboy hat), I finally got a real taste of who he is to people who aren’t nerds and specialists.

Some fears about sustainability grew more acute as TIFF rolled along. In his editor’s letter in the current issue of Cinema Scope, Mark Peranson writes that the magazine, plagued by declining grant fundings and the assorted other pressures wearing on film criticism as an ongoing concern, was unlikely to continue past this year as a print quarterly. Yet the magazine’s annual TIFF capsule package—a gig so many writers, young and established, have passed through over the years, yielding hundreds of pieces from eclectic sensibilities and covering every corner of world cinema—was as heroic an undertaking this year as ever, truly taking the pulse of the festival. Required reading, Cinema Scope’s TIFF coverage is also a necessary community (just like my group chat) — so much so that we joked that, though no one was sure that there would be a ‘Scope party this year, we’d all end up on the roof of Queen West's Bovine Sex Club at 10pm on Tuesday anyway, like the zombies returning to the mall in Dawn of the Dead. As it turns out, there really was a party, attended, or so I’m told, by both Nickelback’s Chad Kroger and Bertrand Bonello, whose Extremely Online The Beast likewise entwines multiple discordant worlds (there was a Nickelback documentary at the festival, and the band played a show outside while I was watching The Human Surge 3).

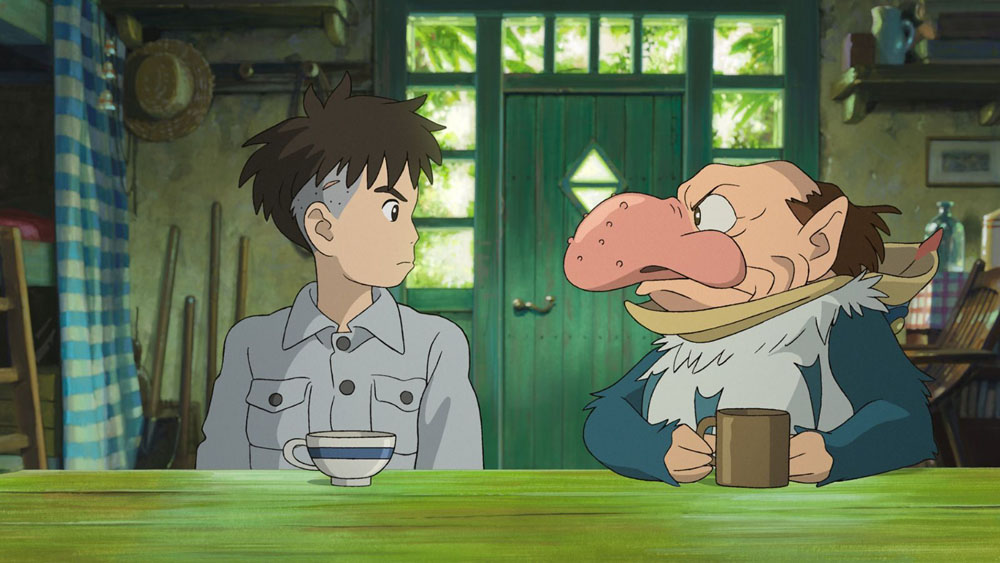

The crossroads at which Cinema Scope has arrived had an echo onscreen in a couple of the festival’s best films, by the octogenarian Hiyao Miyazaki and the nonagenarian Frederick Wiseman, both about the continuity of tradition. In Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron, an adolescent traverses a magical world to meet the grizzled wizard who fabricated it; a metaphor for the artist and an embodiment of the weariness and hope of old age, the wizard implores young Mahito to continue the tradition of world-building, and to “build [his] own tower.” Wiseman’s Menus-Plaisirs les Troisgros looks at a family-run French restaurant; in typical Wiseman fashion, the four-hour film examines every aspect of the restaurant and traces outward its every point of contact with the world, particularly in scenes depicting chefs visiting vendors, chiefly organic farmers, who explain in detail their sustainable practices. I’ve seen many Wiseman films in which person-to-person interactions were more revealing either psychologically or sociologically; these staged-seeming farm visits function almost as info dumps, though this imparting of all the accumulated wisdom that goes into running a three-Michelin-star kitchen takes on more significant weight in the film’s final movement, in which the restaurant’s proprietor speaks of his plans to someday hand off his parents’ and grandparents’ restaurant to his children, of whom he is so proud.

I come away from TIFF 2023 thinking about community-building and institutional support, and what the two have to do with each other.

Elissa Suh

For a small moment upon arriving in Toronto everything felt exceedingly foreign to me: the Ontarian friendliness, bustling disarray of festival prep, the tyrannical outgrowths of construction. I don’t think I successfully reached a destination on my itinerary without zigzagging Frogger-style around sidewalks closed for cranes and scaffolding, causing my daily step-count to skyrocket, even as I outpaced Google’s estimated walking times by at least a quarter—which was monumentally helpful when it came to line up for screenings. A festival naif, I chose my lodgings based on their proximity to the theaters, constellating around one Hyatt Regency, in what I later learned from local critics was referred to as “condominium wasteland.” On my walks I encountered daily the functional blandness of skyscrapers and corporate offices but also noted Mies van der Rohe’s noble obsidian structures, now eclipsed by new construction, and Calatrava’s ornate covered walkway discretely couched between two buildings. There are charms and provocations—Frank Gehry’s forthcoming luxury residence, which resembles a rotating greeting card-rack, notwithstanding—if you know just where to look.

Closing the physical gap between myself and the stars has never been among my chief aims in life, but I wouldn't have balked at the occasional happenstance of it, as typically happens at TIFF. But with the SAG-AFTRA and WGA strike ongoing, the sum total of very famous Hollywood types I saw up-close this year, my first outing, was zero. The Tribecafication of the festival, which programmed a not-so-insignificant number of actor-directed films, was belied by the conspicuous lack of celebrities. I narrowly avoided Chris Pine’s rancorously bad fail-pastiche Poolman, though I have been told it was not nearly as bad as Patricia Arquette’s Gonzo Girl, which I will describe as “hot-girl summer learning to write with Hunter S. Thompson.” It is the type of film in which one character’s description of Anna Magnani’s beauty, “earthy, in a rub-some-garlic-on-her-nipples kind of way,” ludicrously manifests itself as a sort of Chekhov’s gun.

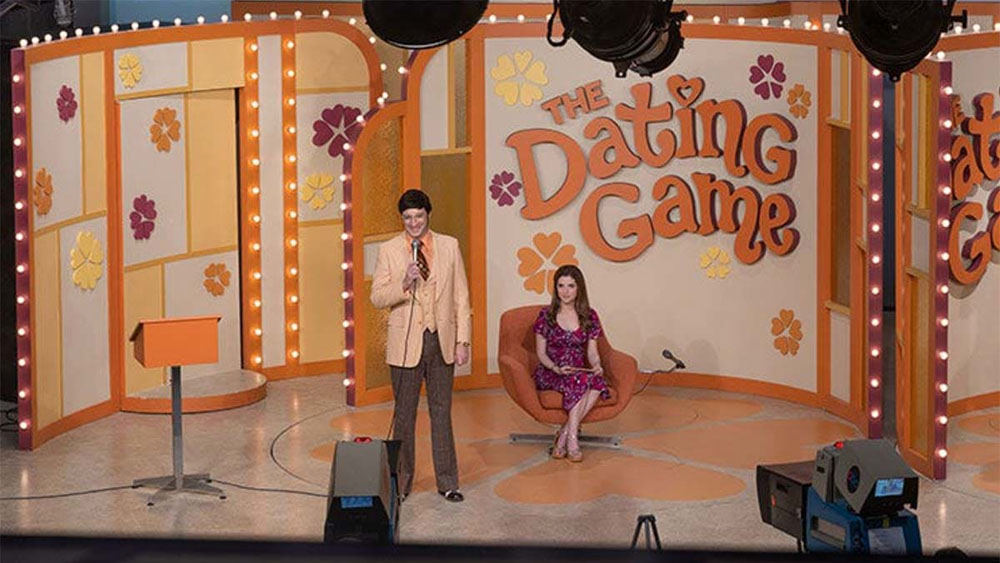

By comparison, Anna Kendrick’s Woman of the Hour (all films 2023), beknighted as property of Netflix for $11 million, felt like a masterpiece (it isn’t) with its two-handed narrative structure. Sophistication! One thread follows serial killer Rodney Alcala (Daniel Zovatto) on a cross-country rape and murder spree, and the other homes in on an aspiring actress named Cheryl (Kendrick) preparing for The Dating Game, in which Alcala also happens to be a contestant. Everything that rises must converge. Fatigued by industry sexism in particular and the male gaze more generally, bachelorette Cheryl swerves drastically off-script, taking control of the production with characteristically Kendrickian quips to the chagrin of producers and the delight of hair-and-makeup. In her filmmaking debut, Kendrick inelegantly unites the stories under the broad guise of how women are compelled to negotiate their encounters with men. Also somewhat ironically, the film’s depictions of violence come off as regressive stylizations, in the manner of true-crime serials that aren’t not part of the problem. Mostly, Woman of the Hour ignites a desire to watch a David Fincher film, which we’ll soon be able to do, thanks to Netflix.

Should the striking writers and actors fail to make headway in bargaining they could always try dipping their toe into Satanism, like the organized workers in Working Class Goes to Hell.

After enduring the loss of friends, family, and colleagues in a devastating factory fire several years prior, a labor union in a small Serbian town finds itself in a futile protest against the construction of a new incinerator. Met with disappointment, they turn to ancient pagan rituals. An unhinged choice for a midnight viewing, this film plays like a wry sociopolitical fairytale rooted in the Yugoslav Black Wave, which critically examined the post-Soviet landscape of the Balkans. A silent faith-healer crops up around town, and the occult does seem to provide some psychic benefits, doing wonders for the workers’ self-esteem. Adopting an ashen-winter palette, Mladen Đorđević takes his sweet, sweet time letting the picture unfold, backloading the action to the final moments, not unlike Bacurau (2019), and sprinkling wry bits of humor throughout. Bungled blood sacrifices and uninhibited nudity help to lighten the somber mood. Not everything coheres as satire, but I found some gratification not just in the film’s climactic violence, but also in how the film grants an intimate glimpse into the town and the workers’ relationships. You feel as if you’ve spent some time with them, and when their faces fill the screen, you are no longer among strangers.

If the eruptive denouement of Working Class Goes to Hell pulls the picture together, the final scenes of Shame on Dry Land transport you to another film altogether, whipping things into a convivial frenzy. Axel Petersén’s riveting, sunglutted noir, set in Malta amongst a wealthy enclave of Swedish expats, is high on style and morally dubious characters. Dimman (Joel Spira) covertly arrives on the island to make amends with his former best friend and business partner Frederik (Christopher Wagelin), whom he fucked over some years back. Frederik’s still sore about it, and Spira plays the offending party like Jeremy Strong might, with fretful intensity, laser-focus, and a penitent disposition that borders on the pathetic. Soon slotted into the role of amateur detective, Dimman follows a convoluted trail of debts and favors in an all-in Dashiell Hammett–style plot that delays its revelation until the final moments and culminates somewhat shockingly in a pop-song cover destined for the annals of cinema history. I once referred to Azor (2021), another stylish thriller that plops you unawares into the unscrupulous dealings of the uber rich, as a Bottega bag: sleek but unflashy. To continue the analogy, I pronounce Shame on Dry Land a Gucci: classic structures fortified with flamboyant left-field flourishes. The aggro-dork antagonist, the cougarish femme fatale, the speedboats—it will all make sense.

Each public screening at TIFF is prefaced with an “thank you” PSA from the festival dedicated to the fans, “the world’s best audience” that enjoys foreign documentaries as much as slashers. This proved true when I found myself seated next to a septuagenarian enamored equally by Dicks: The Musical and a quiet Icelandic film but thoroughly put off by some of the Canadian fare, which she deemed unfinished. “Why do they keep choosing films that need more work?” she asked. (Thankfully she wasn’t referring to Atom Egoyan’s Seven Veils.) I didn’t get to ask her what she thought of His Three Daughters, but I didn’t have to: a wave of sniffles rippled across the audience in Scotiabank 3 during the last act. With thespians like Carrie Coon, Elizabeth Olsen, and Natasha Lyonne in tow, the film invariably showcases some fine performances. As three loosely allied sisters—bossy, spacey, and misunderstood, respectively—they tiptoe around each other's moods and egos while preparing for the death of their father. Azazel Jacobs ensures no one will accuse him of creating a superfluous filmed play by making creative use of the single location of the rent-stabilized apartment and satisfies Lyonne fans with an arbitrary scene at the bodega. Sequestered in tight quarters, the camera cashes in on the claustrophobia while also exposing the distance between the three women. When all is said and done, I don't think I care much for Jacob's brand of persistently nuanced drama, all too neatly contained.

I went to the festival this year thanks to their media inclusion program for early-career journalists, which required attendance at mandatory panels. Amidst logistical tips on pitching and interviewing, my cohort and I were also advised to network laterally; strive to be pull-quoted on a movie poster; and cultivate a TikTok, Reels, or Youtube channel presence in the immediate future, lest we want to settle in the dust. A panelist also instructed us to note the distinctions between critics, movie reviewers, and journalists, but the proverbial bell rang before I could ask anyone where I landed on the spectrum.

I was preoccupied with my film-writing identity when I walked into Hit Man, a Doestoyevskian comedy that poses questions regarding self-perceptions and actions. Philosophy professor Gary (Glen Powell) moonlights as a fake hit man in an undercover sting operation. Suiting up in a variety of costumes—one of the film’s premier joys is watching Powell’s vigorous range manifest in a wild variety of assassin-personae, at times aping Statham, Bale, McConnaughey—Gary undergoes steady transformation from extraordinarily unexceptional man with cats to charismatic and capable alter-ego Ron. The movie loses a little steam once Gary-as-Ron falls in love with a would-be client (Adria Arjona) and must maintain his fake identity. The character’s spark lies in his duality, and the contrast in Powell’s chameleonic range is no longer on display past a certain point. I failed to find purchase in the romantic chemistry between Powell and Arjona, through no fault of their own. As the film went on, it was easy to pinpoint why: the name of Linklater’s game is roleplay, and something so manufactured can only be so moving, or sexy. Though the sanitized cuteness is indicative of Linklater’s overarching vision, making light of more ponderous things like murder and morals, relieving them of their solemn weight.

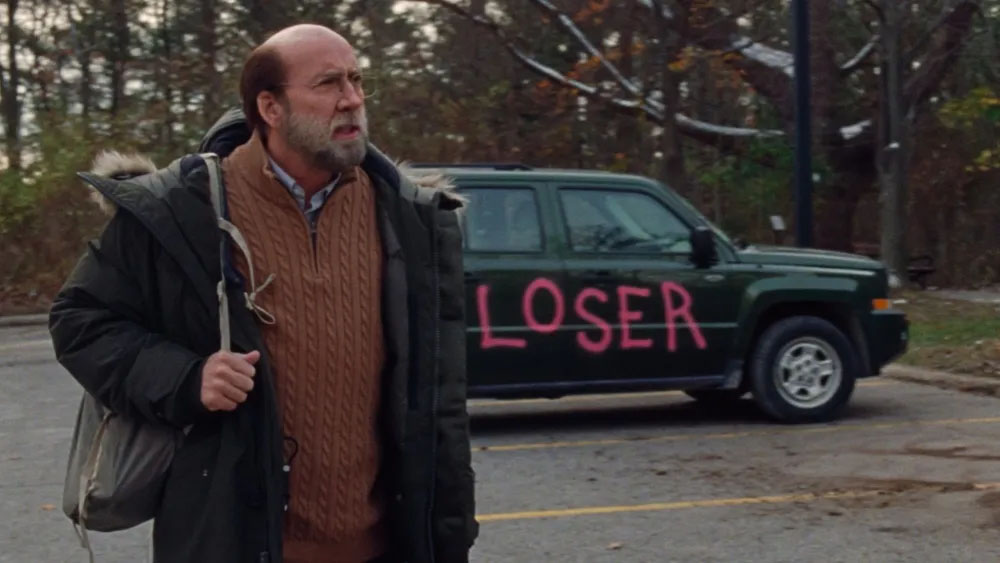

Another film about an unremarkable man who is also a professor: Kristofer Borgli’s crowd-pleasing second feature, Dream Scenario thrusts Nicolas Cage into the spotlight as an agreeable milquetoast in the Massachusetts suburbs who crops up in people’s dreams. At first a helplessly passive bystander, his midnight persona shifts to reflect his psychological state. While the film skillfully harnesses the power of Cage and tempers the more outré tendencies of his showmanship, it crystallizes itself as a disappointingly incomplete yet on-the-nose treatise on memes, influencers, and cancel culture. Michael Cera shows up in a minor role as brand agency co-founder looking to arrange collaborations with Obama and activations with Sprite: a bit of stunt casting that mirrors that of Adam Brody as a powerful but also considerably chilled-out movie exec in American Fiction: awkward rumpled dorks flourishing in their inevitable positions of power.

Maxwell Paparella

Filling one's days with moving images in dark rooms can produce a certain delirium, an effect that may be exacerbated if what lies beyond and between such rooms is also not entirely familiar. Such is the premise of the international film festival, which combines an intoxicating rate of media consumption with the awe, exhaustion, and melancholy attendant to travel. The stimulations of the screen are folded into an already disoriented mind, trying to learn or remember the local customs (strict moratorium on jaywalking, generalized acceptance of non-threatening eye contact) and routes (up Spadina to the $5 banh mi sold out of a building where the anarchist Emma Goldman once lived, through Kensington Market to The Beguiling, the venerable comic-book shop whose bargain basement cannot be beat for selection or price). With my mind thus set adrift, moments from films begin to assume the same aspect as moments from life, which in turn have become indistinguishable from fragments of dreams. It's all a bit muddy by the end of the week, like the stray cheese curds swirling around at the bottom of my umpteenth plate of poutine.

The standard-issue stupefaction was exacerbated by the fact that many of the best films I saw at this year's Toronto Film Festival have other films inside them. Radu Jude's Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, a caustic romp through the injury and indignity of labor in modern-day Bucharest, models itself after an earlier Romanian film, Angela Moves On (1981), which it quotes at length and whose characters it revives, played by the original actors. Kleber Mendoça Filho's Pictures of Ghosts is a paean to the built environment in which a man has come to know cinema and himself, triangulating the landmarks of downtown Recife, Brazil, (including a temple to film that is now an evangelical temple to God) by use of his own films and others. Blake Williams's Laberint Sequences presents in sumptuous 3D the interstices of Barcelona's historic hedge maze before redubbing scenes from William Cameron Menzies's The Maze (1953), with Deragh Campbell providing a capable mid-Atlantic accent. The co-protagonist of Rodrigo Moreno's The Delinquents ducks into a screening of L'Argent (1983), and indeed the tight-again-slack-again bank-heist film left me in much the same mood as do Bresson's, ennobling the solitary passage from the cinema to a bar, articulating and emphasizing each footstep and twitch of perception.

In Do Not Expect, we spend most of the runtime riding shotgun with Angela as she navigates snarls of traffic between appointments with victims of factory accidents, who audition for a workplace-safety video. She snaps gum to keep herself awake and pulls out her phone when inspiration strikes to perform in deepfake drag a chauvinist reactionary pastiche for her online following. "I criticize by way of extreme caricature!" she proclaims when pressed. Jude's Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (2021) might have fit that description, indulging a fantastical eruption of pathos in its final act. In this outing, his critique remains essentially grounded in realism, though our reality is of course absurd.

The hired driver figures prominently in this year’s selections, a dispossessed subject who perceives a ruined world from the windows of an automobile, into which they admit strangers or strange goods. The cabbie, the courier, the production assistant, and even the aid worker variously fill this role. In Ali Kalthami’s Mandoob, a hapless Saudi call-center operator moonlights as a deliveryman, uncovering in the course of his rounds a bootlegging operation that spells opportunity for paying his legal fees. Maciek Hamela, the director of In the Rearview, ferried Ukrainians to the Polish border in the early weeks of the war, employing a cinematographer to capture their raw reactions as he drove, avoiding landmines and Russian-occupied territory. In the final sequence of Pictures of Ghosts, Filho plots an obscure course through Recife for his ride-share driver, who is pleased to meet an artist and proud to show off a newfound superpower.

Seeing so many films at a stretch, usually three or four in a day, one is primed for the recency illusion, a tendency to notice something again after first having become aware of it. Everywhere in these films, it seems, grown men run off to join children’s ball games. Cars are searched at police checkpoints. Childless women give meaningful looks to clueless men. People draw lots by means of rock-paper-scissors (a Ukrainian child augments those options with a fourth: the gun, which she reasons beats everything but scissors). Bodies are exhumed, or suspected to have been, as when Miko Revereza’s grandmother cannot at first find her Filipino ancestors’ resting places in Nowhere Near. These are coincidences; perhaps they only mean as much as we allow them to, though the shuffling of corpses may have something to do with Jude’s injured auditioners. Maimed but not killed, they are put back to work. Meanwhile, the side of the road is lined with markers for slain motorists.

In the course of displaced ethereal wandering, certain subjects snap one back into one’s body, perhaps only to leave it cold. Hit Man is supposed to be a sexy movie, but it is not. Glenn Powell and Adria Arjona commence a purpose-built physical relationship under Richard Linklater’s direction, premised upon a case of secret identity. It could work, except for the problem of chemistry and the fact that Linklater's idea of kink is a Spirit Halloween airline pilot's costume. There is one hot scene, in which Powell coaches Arjona with a series of Notes-app advisories as their faux argument is recorded by a police wire. Powell, who also co-wrote, plays a Nutty Professor type, transforming outside of the classroom into a dashing dirtbag for his undercover side job with the cops. His Cheshire Cat good looks cannot accommodate the nebbish end of that spectrum, and as scoundrel-seducer he does not exude half the masculine mystique of a Jerry Lewis, I’m sorry to say.

There were several very sexy films at the festival, if your idea of sex has something to do with shame, humiliation, and failure. Wang Bing's Youth (Spring) documents mostly teenaged garment workers in Chinese sweatshops. They live in shared, co-ed dormitories and, hormones being what they are, spend whatever time they are not diligently sewing the linings into children's sweatpants teasing, chasing, roughhousing, and groping each other, retreating finally to their beds alone to smoke, scroll, and soak their feet in the hot water left over from making ramen. Denis Côté's Mademoiselle Kenopsia is set in an abandoned hospital, where a lone woman makes ruminative phone calls and possibly sees a ghost. When a handyman drops by to install a security camera, her stern, impassive features melt into a riot of coquettish blinking and pursing of lips, to no avail. Mladen Đorđević’s Working Class Goes to Hell pairs a greasy Satanist with a grieving widow: their sex is rough, bloated, needful, a form of infernal prayer.

The pre-roll of every TIFF screening includes a tasteful, if anodyne, land acknowledgment of the First Nations peoples whose land the city of Toronto occupies. The text is accompanied by images from the films of Alanis Obomsawin: windswept fields, sun-kissed flowers, young people at play in a stream. It was not until I visited The Children Have to Hear Another Story, the artist’s current exhibition at the University of Toronto Art Museum, that I understood these clips are not excerpted from landscape films or quiet, observational documentaries, but rather from fervent advocacy films on such subjects as the assault of Mohawk women and children with rocks as they crossed a bridge into Montréal (Rocks at Whiskey Trench, 2000), or a Manitoban school where Cree students are taught their people’s history in addition to the colonial curriculum, an attempt to repair the generational trauma and cultural erasure of Canada’s murderous residential-school system (Our People Will Be Healed, 2017). Obomsawin is referred to as “legendary” in TIFF’s caption; when she came to prominence as a folk singer in the 1960s, she received another honorific from an adoring white public: “Princess.”

Such frictions and resonances were enough to drive me out of my addled reveries and more humbly into the place I visited, which can only be caricatured by a newsy dispatch such as this. One cannot forever wool-gather, and so I begin now to wonder what it all means, these shared delusions and urgent missives from the silver screen. As for Toronto: I am glad to be home, and I miss it already.