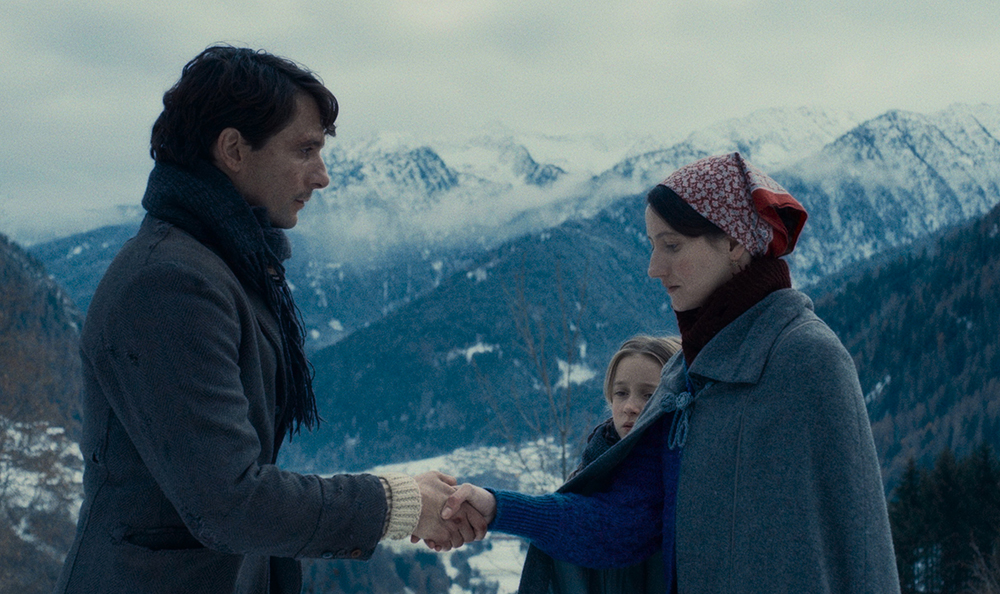

Set in 1944, Vermiglio (2024) presents an unpretentiously novelistic portrait of the sprawling Graziadei family in the small, titular alpine village. With drama unraveling incrementally and slowly accreting meaning, the film brings into focus the three eldest daughters. The youngest concentrates on her studies; the middle grapples with her burgeoning sexuality; and the eldest falls in life with and marries a Sicilian deserter, leading to significant and unexpected repercussions. The passing of time in Vermiglio, and Vermiglio, is contemplative, marked by the milking of cows and minimal dramatic flourishes.

The chilly agrarian setting is lushly photographed and undeniably breathtaking—but Delpero refrains from only fixating on the scenic splendor, fashioning an understated feminist drama. Putting her own spin on a tradition of Italian filmmaking forebears—like Luchino Visconti and Ermanno Olmi, who zeroed in on the political undercurrents of the countryside in films like La Terra Trema (1949) and The Scavengers (1970)—Delpero captures not merely a way of life in decline but explicates upon that particular moment when the shift occurs from one mode of existence to another.

On the occasion of her film’s release, Delpero and I discussed these societal transitions, the paintings that served as cinematic inspiration, and what smell reminds her of her childhood.

Elissa Suh: In your director's notes, you describe the making of Vermiglio as creating a family lexicon. Can you just talk a little bit about what that means for you?

Maura Delpero: I'm fascinated by big families and individuals who are inside a community. Individual destinies are strongly influenced by the destinies of others, like siblings, fathers, and mothers. Of course, this also has to do with the period I'm talking about. The film takes place at a time in which this type of community was still very strong. It ends just a year later, but we feel that much closer toward modernity, where we lose a little bit of this sense of community.

ES: The movie unfolds with a lot of restraint. There are subtle, incremental disruptions that make up the film. Did you have this sensibility in mind while writing the script, or does it emerge during the editing or another point?

MD: It’s really the inner soul of the film and my language. I don't like the “fist in the face” feeling that some films give you, where the emotions hit you hard and knock you down. I prefer to work in a more subliminal way. The film is like an oil stain that grows slowly and touches deeper layers. My method is adding details gradually, like a snowball accumulating over time. I think this approach resonates longer and more deeply, if you can be open to it. It requires a lot from you, but it’s designed to transport you to another time and space. If you enter that tunnel of time and space, it’s as if you stay with them in this ordinary world.

I also find it interesting to remain in the status quo of an ordinary world, only to introduce a twist in the middle of the film that shakes you as the characters are shaken. These surprising events can hit you hard, much like the unexpected moments that occur in our everyday lives.

ES: I read that your father grew up in Vermiglio, which serves as the setting. What was that town like when he grew up and how much of your family’s past made their way to the film?

MD: A lot. He was the youngest of a family of 10 kids. I was born in the city, but we used to go to the mountains all the time to my grandparents’ house. It's still there and I spent a lot of time there for research. It’s a whole world, one that I felt deeply during my childhood. While writing the script, I discovered that I had a lot of sensory material to grab from. The worlds you get to know when you're a child are very strong because of how you absorb them. You don't have any defense; they arrive directly into your belly. When I began to write, I felt that I had all that world in its sensoriality inside me. It was just a matter of structuring it—an entire world of smells, taste, language, sounds.

ES: There are so many little touches that I found really helped complete the tactility of the movie—when they have the linen and cabbages on the baby's head, or even just small details like the children stretching before class on a cold morning. I assume those are all rooted in a personal past or communal past of the village?

MD: It's a mixture of family and town traditions—from my own souvenirs, interviews with my aunts, and interviews with the old townspeople.

ES: Is there a specific smell for you that evokes this movie, or this time and place?

MD: The hot milk in the freezing mornings. It comes directly from the cow.

In terms of costumes and other aesthetics, I wanted something that felt both organic and cohesive, based on a limited palette of primary colors that recurred throughout the walls, costumes, and color correction. We had a color corrector on set. I chose the costume designer because I knew he studies a lot and he's passionate about his work. He's really very philologic. We stayed true to that time period but also incorporated some clothing that felt more antiquated to reflect the isolation.

ES: I found the blues of the sweaters were really striking. They’re a shade of dye that you don’t see very often.

MD: Vermilglio is the name of the town and it's also a color, a type of red. But I always thought the name was wrong. It should be a kind of blue because when you're there, in Vermiglio, the sky feels so, so near. I told the DP that light blue would be our color.

ES: Speaking of the sky, I find that in a lot of movies with mountains, it's their majesty that gets emphasized. In your film, the mountains are definitely enveloping, but they're almost omniscient and more austere.

MD: It's interesting that you mention omniscience, as it contrasts with the idea of a nice backdrop. I didn't want to create this nice postcard image despite its beauty, because in the film nature is larger than life. It’s like romantic paintings, where humanity appears so small against the vastness of nature, which is beautiful but also dangerous. It can be a killer.

This idea of something embodying both beauty and harshness is what the Romantics referred to as the sublime—something beautiful that evokes fear because it is far more powerful than we are. Of course, we worked on this with Mikhail Krichman [the cinematographer]. All the references I passed him at the beginning were paintings.

ES: What were some of those paintings?

MD: One of the main references was Giovanni Segantini, particularly all the winter paintings, like The Bad Mothers. Romantic period paintings by [Caspar David] Friedrich and [Gustave] Courbet. I passed him a lot of Flemish paintings and even some Danish porcelains because of this light blue.

ES: Did you have any siblings or grow up in a big family? I'm just thinking of how you capture the relationship between all the siblings and sisters so well.

MD: My father maintained close ties with his sisters, and they were very unified. But I was actually thinking more about my relationship with my cousins, and my father's family. I only knew them as adults, but they had this bond where they acted like they were young siblings. I envisioned this large family as a community that moves together. Unfortunately, I didn't have a big family myself, but I would have loved to! The dynamics of large families are a fascinating study of different human temperaments. It’s so interesting to see how they are all products of the same tree, yet each one has a distinct personality.

ES: Even though Lucia is kind of the central figure of the movie, I thought of Ada as the guide to the world of the film.

MD: Ada really has the temperament of the middle sister—the one who often goes unnoticed. This gives her a sadness and an urgency, a need to be heard, which she finds in the church. I also think the sisters are intertwined becauseAda would have been different without Flavia and vice versa. Throughout the film, you can observe various dynamics, such as trios and couples. Ada serves as the common link in this chain. As the middle sister, she understands Lucia’s experiences because she is older and has insight into what has transpired.

ES: Her discovery of pleasure and desire made her feel like a more modern and contemporary character, too.

MD: You can see how just two generations ago, female desire was really like a sin. She shares the same nude books with the father. But for him, it's just a time for cigarettes. For her, it's an enormous punishment. You have empathy for her because her sexuality is like ours and you understand how difficult it would be to live in her circumstances.

Flavia represents the sister of the future. As the youngest, she embodies a more modern outlook, shaped by the privilege of being loved and appreciated by her father, who balances both traditional and contemporary views. One of his modern aspects is that he encourages a woman to pursue her studies rather than a man.

ES: The oppressive patriarchy that runs through the movie is sometimes subtle. There's one point when the priest tells Ada, “Your body needs four weeks after the baby to cleanse itself.” Perhaps it was lost in translation, but I found it intriguing that he uses the term "cleansing," implying that having a baby is something negative rather than framing it as a process of healing.

MD: That tradition is Catholic and not just Italian. All Catholic nations have historically viewed childbirth as something unclean. It’s striking because, while it may seem like a small detail, it reveals the patriarchal society we live in. These women not only endured nine months of pregnancy and painful childbirth, but were also considered impure for 40 days afterward. The Church played a significant role, not only in religious terms, but also as the social center of the community. During this time, women were excluded from gatherings because they were deemed dirty. I knew that in depicting this, I had to stick to the codes of the time. It would have been a big error to impose my contemporary woman’s gaze on it.

At the same time, I see this as a historical moment that represents the end of an era and a transitional period. It’s fascinating because, although the characters feel completely out of sync with our modern world, they are already part of a new reality filled with contradictions. See how they’re yearning for self-determination while still being confined by societal codes. They’re boiling inside, and characters like Lucia experience this shift through her tragedy, and not through feminist theory, which will come in the seventies.

They are truly transitional characters, helping us understand our very recent past. Reflecting on their experiences allows us to recognize how much progress women have made in terms of equality. However, they are still close to us in time, and we carry those subconscious attitudes about women's roles. This is why we haven't fully achieved true parity; we still harbor remnants of exclusion within us. It’s a legacy that connects us to our grandmothers—it's just yesterday.

Vermiglio opens today, December 25, at IFC Center.