On May 19, 1992, 17-year-old Amy Fisher confronted her 36-year-old boyfriend Joey Buttafuoco’s wife, Mary Jo, on the front porch of their Middle Island, Long Island, home. Accusing Joey of sleeping with her (fictitious) younger sister, Fisher scuffled with an incredulous Mary Jo, eventually shooting the mother of two in the head. Mary Jo survived the attack and identified Fisher as the shooter, leading to the high schooler’s arrest for attempted murder; Fisher pled to first-degree aggravated assault and was sentenced to 5 to 15 years in prison on December 2. On December 28, the first of three made-for-TV movies about the case, Amy Fisher: My Story, premiered on NBC, followed on January 3 by both The Amy Fisher Story on ABC and Casualties of Love: The "Long Island Lolita" Story on CBS.

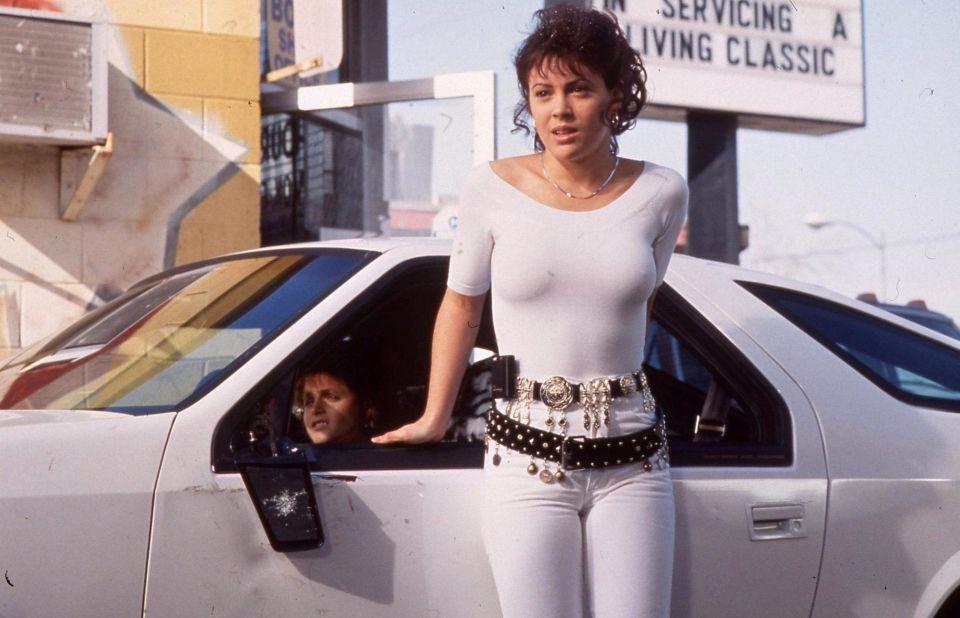

At the time of the initial criminal proceedings, Buttafuoco claimed he’d never slept with the teenager; her unfounded obsession, based on an ordinary flirtation around her frequent trips to the body shop where he worked, had inspired the “fatal attraction” attack, as the news media of the day often described it. This is the angle of Casualties of Love, for which CBS paid the Buttafuocos “several hundred thousand dollars.” Best known at the time for playing Tony Danza’s daughter on Who’s the Boss, Alyssa Milano took on this most unhinged portrayal of Fisher in an attempt to counteract her good-girl persona, inflecting her onscreen interactions with Buttafuoco with a degree of nymphomaniacal manipulation of which the real-life Amy was hardly capable.

Such is the NBC approach to the case; that network reportedly put up half of the $2 million bond on which Fisher was released in exchange for the rights to what became Amy Fisher: My Story. Starring Noelle Parker and the former NFL player Ed Marinaro, this version comes closer to capturing the predatory, tragic nature of the relationship. It depicts Fisher as the victim of physical abuse at the hands of her striving middle-class father and the thoughtless machinations of an older man who, in addition to seducing and assaulting her, made romantic promises he never intended to keep, and pressured her into taking up sex work. Fisher could sense that her family was the least-well to do of their suburban neighborhood; her imagination for what her future might hold failed to extend beyond the somewhat nicer homes on the Island and the more stable families dreamed to be within them. When the headlines first appeared, Fisher apparently asked her mother, “What’s a Lolita?”

The Amy Fisher Story falls somewhere between these two interpretations and was the most successful, likely due to director Andy Tennant (Fools Rush In, 1997; Ever After: A Cinderella Story, 1998) casting Drew Barrymore in the lead. Fresh from her femme fatale performance in Poison Ivy (1992), the star’s presence (and the explicit sex scenes) emphasizes the sordidness of the whole sick affair, resulting in a banal but greasy film. The trio of TV movies, thought to be the first instance of such simultaneous primetime treatments of a recently adjudicated crime, exceeded network executives’ expectations by topping television ratings, despite competing with one another as well as Hard Copy, Dateline, and other coverage of the characters and events.

This unprecedented moment of media frenzy is the subject of Dan Kapelovitz’s Triple Fisher: The Lethal Lolitas of Long Island (2012), which collages the three movies together into an 80-minute riot of sex, questionable acting, hair spray, and muscle shirts. Kapelovitz includes scenes of the actors watching the recreated news coverage of the events the films portray; disparate approaches to video content used by Hard Copy and others to try Fisher in the court of public opinion; recreations of press conferences, personal tape recordings, and by turns sweet and sexy phone calls; and lengthy where-are-they-now-style end credits. The resulting cacophonous, queasy “reduplication of the real” potently situates the affair within the realm of the Baudrillardian hyperreal, where representations proliferate so rapidly and with increasingly obscene detail as to thoroughly leave behind any concern with the grubby “facts” and what they might reveal about a lonely teenager and her world.

Back when Triple Fisher had its East Coast premiere at Videology (now closed) in 2013, Kapelovitz told The L Magazine (also defunct) he’d had the idea to make the film in 1993, but waited two decades for better editing equipment; otherwise, he “would have had to edit the film using VCRs.” Triple Fisher’s VHS fuzz and brittle humor mark it as an artifact of another time, though its potent depiction of the collapsing of “events” and their “representations” remains as relevant—if not more so—today.

Triple Fisher: The Lethal Lolitas of Long Island screens today, November 5, at BAM as part of the series “Let the Record Show: Archived Cinema.”