Last March Screen Slate published Cosmo Bjorkenheim’s “True/False 2020: The Last Film Festival,” a dispatch from the Columbia, Missouri nonfiction film festival that took place as the severity of COVID-19 belatedly captured the public's attention in the U.S. (The festival concluded March 8, three days before the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, and about two weeks before many states shut down nonessential businesses.) As Bjorkenheim wrote then, “So much seems to have changed in the past week, socially, economically, and philosophically, that the world of ten days ago feels like a distant memory. ... Now, more than ever before in our lifetimes, it's absolutely imperative to think collectively rather than individualistically.”

Over the past fifteen months, the concept of a film festival as an in-person community gathering has shifted to accommodate new online formats, and now, as public health guidelines begin to relax, True/False is one of several festivals pursuing a hybrid online and in-person format. To address this change, Screen Slate asked True/False veteran Nicolas Rapold to remotely team up with Bjorkenheim to contribute an IRL vs. URL column. Cosmo kicks things off by reporting from the ground May 5-9, followed by Rapold filing from New York City.

IRL

Cosmo Bjorkenheim

In primordial lagoons, scaly creatures pined for land. Soon they jumped ashore and struggled to process air through their gills until they developed lungs. Over the epochs, struggling to locomote turned their fins into legs. Hundreds of thousands of years of adapting organs for a new environment eventually yielded early land mammals, but it took hundreds of thousands of years of failure to get there.

Such are the painful first moments of all complex systems, from animals to nations. This year — what some consider to be a year imbued with millenarian promise as well as menace — I have the privilege of witnessing the birth of one such system: the film festival. It feels like being present at Adam Smith’s mythical inception of mercantile capitalism, like hanging out in the prehistoric village where hunter-gatherers first had the idea to divide labor among themselves, acquire professions, and start trading goods.

When, in mid-March of 2020, everything everywhere, from concerts to conferences, was being cancelled, the last film festival on earth was taking place in the Midwestern college town of Columbia, Missouri. Toward the end of the weekend, the mood was weird, uncertain. Was this a good idea? Will this ever happen again?

In 2021, the leadership of the Ragtag Film Society, which runs True/False, decided to answer these questions by not allowing the pandemic to compel them to skip a single year of the festival’s still-unbroken 18-year run. Departing from the trend set by heavy hitters like Sundance and SXSW — or even titans within the doc fest world, like DOC NYC and Cinéma du réel — True/False didn’t opt for an online-only edition this year, instead launching an experimental, mostly-outdoor hybrid event that would require its staff to more or less reinvent the event’s entire operational structure.

I didn’t realize what a challenging proposition this was until I arrived in Columbia (or, as some locals call it, especially in the context of asking tourists to support local business, CoMo) and made my way to the Riechmann Pavilion in the city’s 116-acre Stephens Lake Park to pick up my festival pass. Roads leading to the park, in which the festival’s four outdoor screens are all located, were closed, sending confused attendees back to Ragtag Cinema a mile away to park and search for a shuttle that was rumored to transport them to the screening areas. When I asked a box office attendant about the protocol, she sighed and said, “Nobody knows.”

Eventually two yellow school buses pulled up in front of Ragtag. Someone said, “I think these are the shuttles,” so I boarded one. The lady driving the bus was using one hand to steer and the other to hold a printed map of downtown Columbia, with drop-off locations marked in pen. A group of boomers — their hair frizzy with excitement and their gauzy blouses all in different shades of purple — sat in the first three rows and complained to each other about the ambiguity of their official maps of the festival grounds.

We were dropped off at the Riechmann Pavilion and I collected my pass, only to realize that my first screening, starting in 20 minutes, was back at the Ragtag. I walked with Ted Rogers, Ragtag Cinema’s programmer, down the winding path back toward the shuttle drop-off point. “There's going to be some improvisation,” he told me. “The specific protocols for the Q&As” — which Ted is moderating several of — “are not fully nailed down yet.” He spotted Angela Catalano, one of T/F’s two programmers, who was walking up the hill toward us. “The drivers couldn’t find Columbia; that’s why they were so late,” she told us. Ted was incredulous: “They couldn’t find the city of Columbia?” Angela nodded. “We’ll pull this off though,” she said.

I was the only passenger on the shuttle back to Ragtag. It was the same lady driving. “I don’t usually do this route,” she said, unfolding her map onto the steering wheel. “I live in Boonville, 25 miles down the road.” I had already sort of memorized the four turns needed to get to the main strip downtown, so I stood in the bus’s stairwell and directed her.

I made it to the Ragtag only 10 minutes late for Jessica Beshir’s Faya Dayi, a lyrical black-and-white portrayal of several generations of khat harvesters in the countryside around the Ethiopian city of Harar. A teenage boy and his younger brother dream of traveling via Egypt to Europe, but the costs are prohibitive. Their father, like virtually everyone else around them, chews khat habitually, but his tendency to acquire a new personality when he’s high is becoming a problem. The landscapes are breathtaking and the relationships disarmingly intimate.

Sitting in the larger of Ragtag’s two theaters, after a year and change since I was here watching shorts by Ja'Tovia Gary and the Total Refusal collective, for a moment I felt like I had gone back to the Before Times. Every other row is kept empty with a long strip of masking tape, but besides that there’s hardly any discernible difference. It seems the Ragtag has boldly kept its day-to-day as normal as it dares, even as I hear rumors that people outside the theater’s management had misgivings about its reopening last June after only three months of closure.

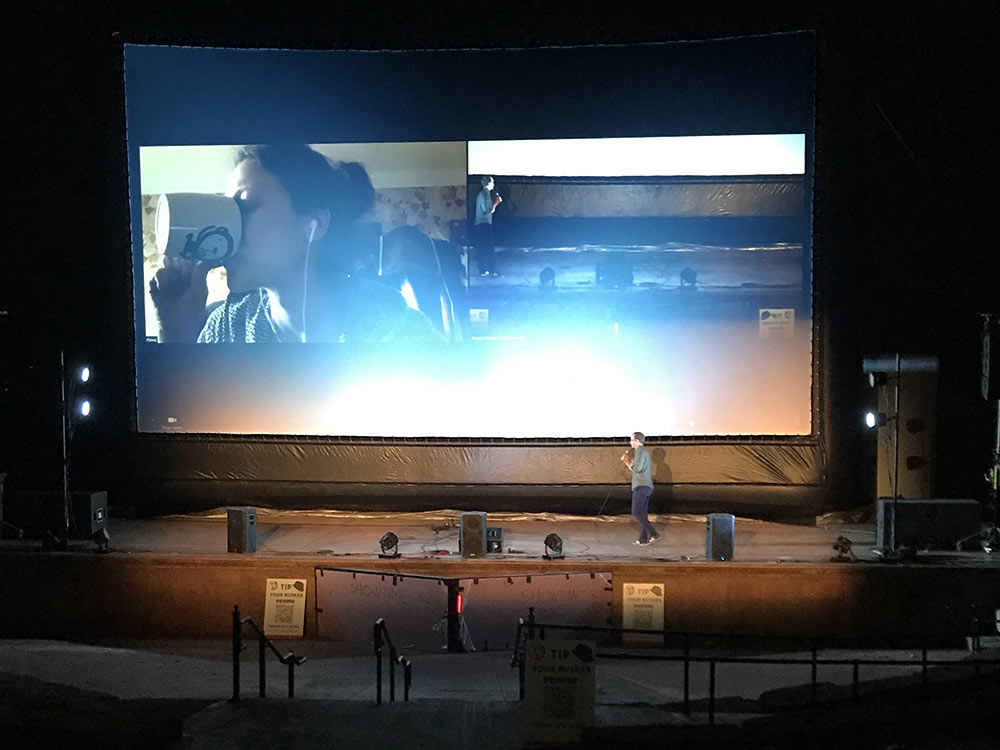

I had to leave early to make it to the next screening back in Stephens Lake Park. I got the bus with the same lady again. “How’s your night so far? Is it starting to get a little repetitive?” I asked. “I’m on duty until midnight, so it’ll get repetitive by then.” I got to an outdoor venue nicknamed the Amphitheater only ten minutes late to This Rain Will Never Stop, another black-and-white doc, this one about a young Kurdish-Ukrainian man from Syria who fled the civil war in 2013 and relocated to Ukraine’s Donbass region where, scarcely a year later, a Russian war of annexation broke out. He volunteers for the Red Cross and devotes himself to doling out supplies to throngs of huddled Ukrainian civilians near the front. After the credits had rolled, Ted got up on stage to conduct the Q&A with director Alina Gorlova, his slim figure dwarfed by Gorlova’s ten-foot-tall projected face as she Zoomed in from Ukraine. There were minor technical difficulties that were mortifying to Ted but charming to everyone else, and as a volunteer wearing an LED-lit tophat pointed out, “You can’t expect to build an outdoor film festival from scratch without expecting some snags.”

Ted and I wrapped up the evening by shivering on soggy grass and taking in a shorts program. In The Flooded House, director Lucía Malandro uses experimental animation techniques to render its subject’s memory of her family home being raided in the 1970s by the Uruguayan military as a reprisal for their involvement with the Tupamaros National Liberation Movement. The combination of unearthing decades-old trauma with distinctive animation that calls attention to its craft recalls Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León’s The Wolf House from 2018. This was followed by Red Taxi, a series of anonymous interviews from 2019 with cab drivers in Hong Kong and in mainland Shenzhen about the mass protests in the former British colony. Amazing shots of Chinese pageantry in Shenzhen’s dystopian, hyper-modern squares while a hack spews the baldest apologies for state terror.

The only thing I don’t look forward to about the next three evenings is that they coincide with University of Missouri’s graduation. I expect to see a lot of white boys in mardi gras beads and flip flops gracelessly gyrating to Rich Homie Quan [ed. note: Cosmo, it’s 2021] blasting from sports bars up and down East Broadway.

***

My second day here was less hectic. I discovered that successfully navigating an outdoor festival with far-flung venues hinges on proper planning. In Columbia, if you’re looking for dinner after 11 pm, your choices are either wings or a local version of Subway, and although it’s 70 degrees in the daytime, the nights can be frigid. An awareness of these factors can reduce your risk of ending up on a frosty lawn with low blood glucose, counting down the feature’s 110 minutes until you can bow out gracefully.

Last night I was lucky to be back inside, in the larger Ragtag theater watching Paloma Sermon-Daï’s Petit Samedi. A gaunt 43-year-old man, Damien Samedi, lives with his mother in a small Belgian village and struggles with addiction. (He’s been smoking heroin for the past 25 years.) Either the mother watches Christian game shows while Damien chases the dragon in his bedroom, or they sit together in the living room talking about his siblings, his childhood, and his finances. Damien mows lawns and does handyman work, but his mother wants better prospects for him; their CV-writing workshop at the kitchen table is endearing, as mom asks Damien what he’s good at, what he’s accomplished, what his address is (she doesn’t wait for an answer — it’s obviously the same as hers), while Damien listlessly goes through the motions.

At first I didn’t know what to make of Damien. He was a sad figure, a cautionary portent of what a life can turn into after one poor life choice and decades of regret and apathy. Is this what happens when a life is so sapped of promise that its only fulfillment is to be found in childhood memories? Damien was clearly a tragic figure, but it was hard to shake the feeling that this bardo of impotent nostalgia was something he had brought upon himself and was not trying hard enough to escape. But the longer Sermon-Daï’s camera stays on Damien, the more I was able to feel the universality of his condition. One mistake in his twenties was all it took to condemn him to a life of self-hatred and despair. He does make choices every day, and he is not absolved of responsibility for his future, but he is also a victim of his circumstances. It’s not that he deserves sympathy because of some abstract moral imperative; it’s that we see beyond the specifics of addiction and into the void that addiction starts by filling. One important choice he has made, which gives him agency, is to go into therapy. As the frame stays immobile on Damien’s face, his therapist just a minimally intervening offscreen voice, we see him struggling with the lasting impact of his father’s abusiveness (some clichés are no less true for being clichés) and the small-town stigma of being known as a user. Whatever personal shortcomings he might have, he strikes us as honest and kind, wanting nothing more than a “normal” life without the weight of the past hanging on his neck (addiction being an exceptionally concrete way in which the past continues to haunt you). Who can judge this man without hypocrisy? Not to bring the Bible gratuitously into it, but “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone.”

After Petit Samedi, I got a lift from my new favorite school bus driver to another outdoor venue in the park, Sled Hill, where Ted was watching The Grocer’s Son, the Mayor, the Village and the World and preparing for his Q&A with director Claire Simon. I watched the last 90 minutes of this tale of a motley crew of documentarians and farmers working together to start a filmmaking school and workshop in the tiny French commune of Lussas. Ted had brought ultra-lightweight REI camping chairs, so my ass was spared the icy conduction of the previous evening. During the Q&A, Ted’s mic stopped working for a full minute, but Simon was gracious and the whole thing had a comradely feeling thanks to the affinity between Simon and company’s rural cinema experiment and True/False’s scrappy ethos.

***

Tonight I saw Theo Anthony’s All Light, Everywhere, an essay film about the intertwined histories of surveillance and weapons technologies. Its main framework is provided by Axon Enterprise’s VP of Communications giving a tour of the company’s headquarters, including its assembly line (where, he proudly announces, every TASER and body camera you’ve ever seen was made by hand), its open-layout offices (where the company’s core values of transparency and accountability are demonstrated), and its “black box” (where the company’s top secret R&D happens). This man seems so eager in his conviction that Axon does socially important work that we almost feel sorry for him when Anthony takes indirect digs at him through unflattering editing. But we soon learn that regardless of its boyishly charming executives, Axon is part of an entrenched history of increasingly granular surveillance technologies that pervade our daily lives in the service of state control. Ever since German pharmacist and inventor Julius Neubronner combined the principles of body cameras and aerial surveillance in 1907 by attaching small cameras to pigeons, armies and police departments have invested in research to develop ways to record as much visual data as possible, as constantly as possible. Of course, as Anthony self-reflexively points out, filmmaking is a part of this tradition.

Upon leaving the theater I discovered that I had once again failed to secure dinner before 9 o’clock, so I drove to a mall with an open-late Culver’s, the Midwest’s response to In-N-Out. One ButterBurger and Oreo® Vanilla Concrete Mixer later I was heading back to the park to catch No Kings and Ted’s Q&A with director Emilia Mello, one of only ten directors to physically attend this year. Afterwards I congratulated Ted on his first Q&A to go off without any technical issues, but there had been a minor hiccup during the screening: the DCP of the film had failed halfway through and the festival crew had been forced to take a brief intermission while they prepared the backup ProRes file. The birth pangs of this new festival model were clearly still being felt on night three.

On our drive home, we passed through a quiet residential neighborhood where, on a dark street corner with no one else in sight, a middle-aged woman was doing a solo color guard routine with two flags: the Stars and Stripes and a “Trump 2020 No More Bullshit.” She flashed a broad smile as we rolled by slack-jawed.

The following night’s in-person screenings were cancelled due to high winds and moved online, and since that meant that they now fell under my colleague Nic Rapold's jurisdiction, we stayed in and spent my last evening watching Magic Mike XXL on Ted and Carmen’s big TV. Soderbergh’s crowd-scene dolly shots and slow zooms were commented on, as was the bro repartee that makes XXL feel like a Howard Hawks movie.

After witnessing the consistently commendable efforts of True/False’s programmers, coordinators, technicians and volunteers as they built a film festival from scratch against the odds and the elements, the occasional glitches — which Ted perceived as catastrophes — were actually nothing worse than quirks that lent character to the weekend. Someone whose name I didn’t catch but who was involved in running the festival in some capacity compared the experience to raising a child: eventually you have to learn to let it live its own life. •

URL

Nicolas Rapold

It’s easy for me to slip into utopian tones when describing True/False’s sharply curated showcase of nonfiction art in the affable university town of Columbia, Missouri. I’m always buoyed by the enthusiastic and curious audiences, whether screening a Sundance concert doc or a hybrid reverie from halfway around the globe. Yet as nice as all that sounds, and as much as I like the pastries at Ragtag Cinema’s Uprise Bakery, I would not return annually if the programming did not remain strong. For that reason, even having attended last year’s calm-before-the-storm pre-shutdown edition, I was not crestfallen at the prospect of experiencing a virtual edition of True/False. If not physically at the variety of True/False’s venues, I could at least see the movies.

“Teleported” was the official moniker for virtual attendance, a term with magical or science-fiction valence that suggested a you-are-there connection to the festival. Teleporters began with a Zoom unboxing of the mystery packages they had received, hosted by True/False programmers against a set that recalled Dr. Clayton Forrester’s lab from Mystery Science Theater 3000 (partly also because Zoom video can remind me of pre-HD 90s broadcast video). The box contents included scents bottled for specific films, audio field recordings (from Emilia Mello, for her No Kings), and other meticulously assembled title-specific talismans, as well as a map drawn by grade-schoolers, sweats, and (my favorite) a matchbox-sized Ragtag. What might sound twee felt of a piece with the communal, handcrafted ethos of True/False which has managed to remain just this side of artisanal branding while delivering the cinematic goods. I viewed the box’s contents as souvenirs of a trip I could not take.

Thereafter, the substance of my True/False consisted of the films, as an unpredictable internet connection left me in perpetual catch-up mode on the virtual front. I would enter chatrooms seemingly after they had already emptied out (though these can feel like Lincoln in the Bardo to me anyway), but I would also mark Q&A’s and recorded busker performances to watch later so as to make the most of my movie-watching windows. (The exception was the virtual equivalent of the closing-night festivities, which I’ll get to later.) The 2021 slate cherrypicked from Sundance and IDFA and from the constellation of nonfiction-leaning festivals off the mainstream radar, overlapping with work by filmmakers whom the festival has championed. Teleporters could access only a subset of this overall slate, and whether it was a rights matter or otherwise, the festival’s streamlining of options served to channel engagement toward films like No Kings or The Grocer’s Son, the Mayor, the Village and the World rather than, say, Summer of Soul (to be released this summer by Searchlight).

Suitably enough for a remote experience, the festival opened with a film that visits and sits with a woman at her home. Memoir as reckoning, by turns raw and raucous, Delphine’s Prayer comes from director Rosine Mbakam, whose film about a hairstylist, Chez Jolie Coiffure, I’d seen at True/False (which this year also showed The Two Faces of a Bamiléké Woman, about her mother, as a retrospective selection). Mbakam shoots Delphine head-on in her Brussels apartment recounting her upbringing and abuse in Cameroon, experiences as a sex worker, caretaking of her children and sick niece, and fleeing Cameroon through a “sham marriage” to a smitten European man. “I don’t trust the Belgian sun,” she jokes at one point in a series of monologues where she lets loose with sadness, mischievous glee, rage, ruminations, prayer, and illusion-free critique informed by her experience of patriarchy and racism across continents, snarled in the long tail of colonialism. Even as her troubles pool toward the film’s end into the despairing frustration of the present, there is the sense of Delphine editing together her own life into her own chapters: Mbakam keeps showing her friend bringing their long-take sessions to a close when she wants to. A bravura moment of communion that perhaps gives the film its title comes when Delphine appeals to off-screen left while speaking to her deceased mother, the camera panning to show family portraits on the wall. (I also liked a pensive interlude where Delphine watches part of a Nollywood movie on her laptop.) Remarkably, Mbakam — who last year found herself marooned in Belgium by COVID restrictions, on the verge of shooting a new feature — originally shot Delphine’s Prayer in 2014 and 2015 shortly after completing film school. The filmmaker ends with a calmly incisive voiceover of her own, reflecting that she might not have grown close to Delphine had they each stayed in Cameroon, united as they were in Europe by their shared apartness.

![Delphine’s Prayer, Rosine Mbakam. Courtesy of True/False.]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Delphines-Prayer.jpg)

Mbakam was honored with the festival’s True Vision Award, and a previous recipient, Claire Simon (The Competition), also showed a feature this year: The Grocer’s Son, the Mayor, the Village and the World — the title recalling Rohmer’s The Tree, The Mayor and the Mediatheque which told the story of a small-town socialist mayor pushing to build an arts center. Simon’s profound portrait of cultural and economic survival tracks the effort to launch a documentary streaming platform and build production facilities in Lussas, a village of 1,163 in the south of France. Rather than the eccentric bid for relevance that the logline might conjure (thanks to a number of such formulaic documentaries), the town’s doc project expands upon a summer festival that already takes place there. Simon highlights the structural challenges and the search for meaning and continuity (with unavoidable echoes of recent Wiseman films but less circling). The specifics could wring a bemused smile from anyone currently in an “org” or festival: securing recognition and funding from an aloof culture minister, devoting long short-staffed hours to initiatives bottlenecked by a visionary leader (Jean-Marie Barbe, the “grocer’s son”), hitting send on that newsletter (cue Mailchimp mention). Simon crystallizes not only the spaceship-air-lock asymmetries of plugging into a global economy and its daunting competitive scale, but also one community’s ability to value and maintain its arts as assiduously as it does its farming. Both of these industries face recurring challenges of precarity — the film shows farmers dealing with a devastating storm (echoed this past spring by a rough frost) — but Simon seems to bet on future prospects as she shows Barbe drinking and chatting with farmers who share his 100-year view of passing meaning along to the generations to come. (Sidenote: the feature was created, seamlessly, from footage shot for The Village, a nine-hour series Simon shot for French television.)

The survival of communal cultures felt like a recurring theme in two other documentaries, Emilia Mello’s No Kings and German Adolfo Arango’s Songs That Flood the River. Giving a ground-level view, often as if crowded into a room with those on screen, Mello captures the rhythms of a Caiçara fishing community in Brazil as she forges a bond with a fearless girl (shown hunting crabs on vast wave-smashed rocks) and a fisherman poet (whose ode ends the movie). Meanwhile, Arango — filming in a Colombian village ripped apart by the 2002 Boyajá massacre (a result of fighting between paramilitaries and FARC — focuses on a woman, Oneida, who composes and sings mournful alabaos to help process the experience of violence and loss. (That is, when she is not spending hours on the routines of preparing food and wrangling family.) Shooting in a rainforest with deep-vanishing-point staging and framing that evoke the intrigue of a slow-burn drama, Arango returns to the haunting image of a worried Oneida speeding down a river, boat pointed straight into the camera — a kind of troubled dreamflight (in a doc that already features a dream sequence).

For this dispatch I’ll also save a word for Danish filmmaker Robin Petré’s From the Wild Sea and the festival’s energetic shorts programs. Premiered in Berlin in the oft-overlooked Generation section, From the Wild Sea looks at marine mammal rescue efforts off the coasts of Ireland and England from a hypervivid subjective perspective. While described as chronicling the tireless humans saving and caring for injured animals, what struck me most was Petré’s evident interest in getting inside the headspace of seals. Close-ups tune us into their puppyish eyes and whiskers, with camera heights placing us at their level, heralded by the opening shot of a seal being released from a cage back to the shore and ocean. I was awed by the herculean task of rehabilitation, but what sticks with me is a seal leaning casually against his tub in an amniotically lit holding pen, like a space capsule painted by an Old Master. Or hearing the POV underwater sound design for another seal dipping in and out of the water. The animal body dominates the frame more than the often cropped people; I can still feel the heft and bob of the swans carried in one scene from one room to the next, survivors of an oil spill. Petré is neither sentimental nor clinical; her renderings of the animals are warmly real yet we are also reminded of the ruthless odds of survival faced after maiming or poisoning by manmade waste.

Of the shorts I’ll single out the Sturgeon 73 Program, which alone included the superb Red Taxi’s dueling cabbie-on-the-street takes on Hong Kong protests and suppression, from either side of the Chinese propaganda firewall; animation-FX-augmented Flooded House, evoking the ghostly and horrific in Uruguay’s political history with 1991 VHS home video; Lemongrass Girl, a behind-the-scenes mood ring for Anocha Suwichakornpong’s Berlin-premiered Come Here; Halpate’s brief history of Seminole alligator-wrestling culture; and the structuralist iterations of Kevin Jerome Everson’s The I and the S of Lives, locked onto a roller-skater circling in earshot of Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

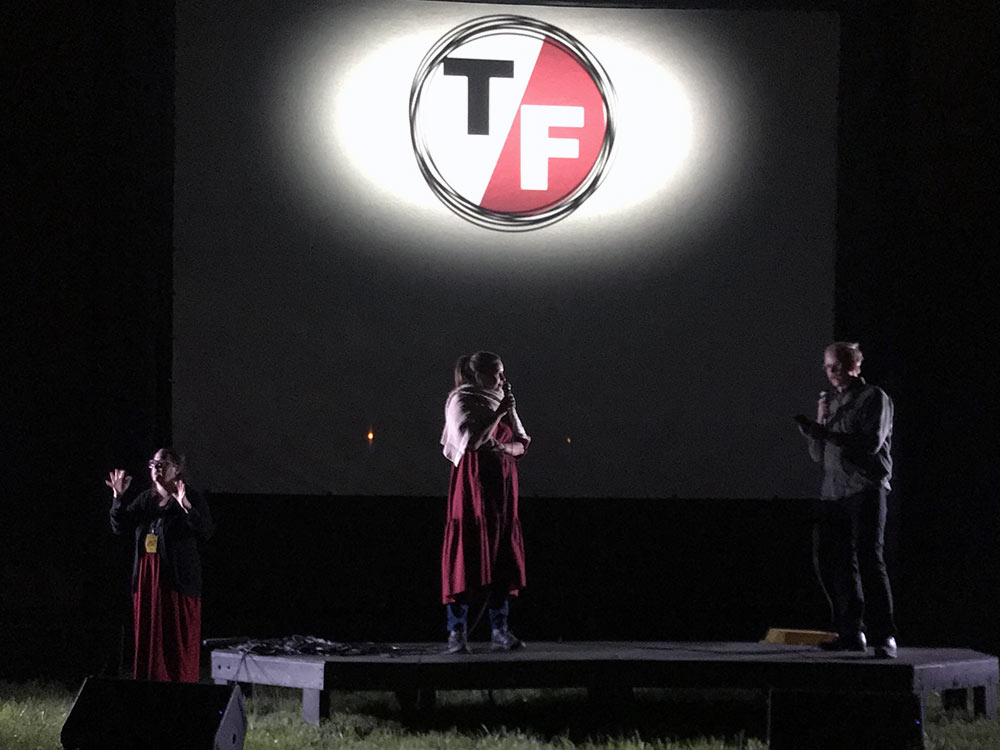

For a closing-night celebration, True/False conjured a surprise preview of Eschaton, The Next Chapter, variously billed as a nightclub experience and immersive performance venue. (It opened this past weekend to sold-out audiences and, appropriately enough to these hybrid circumstances, was originally conceived in a prior incarnation as an IRL endeavor.) Live performers loomed in virtual rooms, ranging from cabaret to puppetry to pole-dancing — and assuredly more, but I was again hobbled in my wanderings by balky Internet. In any case, the remote audience was not spared: “Nicolas Rapold, you are a mystery,” one crowned singer intoned to my faceless Zoom ID box, shortly after riffing on Slate critic Sam Adams’s book-lined backdrop to the effect that he looked “ready to quote Milton.” It was all a fitting note of playful plenitude to end on, equally surreal and intimate. And in the partialness of my viewing, I was only encouraged in the lifelong feeling that there is always more to see. •