The theme of this year’s True/False Film Festival was “The Human Paradox,” a nod to the plurality of truths that exist within the documentary genre and the ways in which we embody them. As the festival guidebook states, “instead of passing judgment on inconsistency, we are reframing contradiction, looking towards the possibility in paradox and the expansion in the ability to exist outside of the expected.” As the eager crowds of Columbia, Missouri, poured into university halls, ornate theaters, and repurposed churches, the antinomy of storytelling and mythmaking seemed to color the air; festivalgoers knew they were lucky to peruse such paradoxes together. The festival housed some handsomely received Sundance residuals, such as Girls State (2024), the trad twin of Boys State (2020), about the American Legion Auxiliary's state-wide “interactive government-in-action experience,” and Daughters (2024), the winner of the Festival Favorite Award at Sundance, which surveys an initiative that organizes a father-daughter dance inside a Washington penitentiary, and the ten weeks of requisite counseling the incarcerated fathers must complete leading up to it. I am allergic to girlboss aesthetics, so the former was more like an exercise in birdwatching, but I found the latter’s attentiveness to the ways daughters hold grief, anger, and affection at once very moving.

In Jazmin Jones’s enrapturing hybrid doc Seeking Mavis Beacon (2024), the filmmaker and her associate producer Olivia McKayla Ross (a poet-programmer and “cyber doula”) set forth on a decidedly niche undertaking: locating Renée L’Espérance, the Haitian woman who modeled for the computer software Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing in 1987. The film is an exercise in collective memory, with several interviewees revealing they believed Mavis Beacon to be a real woman when, in reality, she was one of the first consumer-facing AI figures. Jones and Ross’s search considers both sides of the camera as they investigate the ethics of the software developers and their own potential breach of L’Espérance’s privacy. Seeking Mavis Beacon folds in thoughtful asides on glitch feminism and critical fabulation, as well as possibly the first successful integration of memes into film. The film is configured with a keen understanding of the moment in which it emerges and of when Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing hit the market. By plaiting together archival footage of Mavis Beacon advertisements and latter-day TikToks, Jones communicates the continuum of Black women’s marketable labor and subsequent lack of recognition. (In a delightful act of critical juxtaposition, a verbose Anaïs Nin quote and the video of a girl dancing in an Apple Store are stitched side by side.)

True/False also held the world premiere of Yintah (2024), co-directed by Brenda Michell, Michael Toledano, and Jennifer Wickham. The documentary is a 14-year record of Wet’suwet’en sovereignty and their resistance to the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Yintah closely follows activists Howilhkat Freda Huson (a Wet’suwet’en chief) and Sleydo’ Molly Wickham (a Gidimt’en clan member) in their struggle against CGL’s pipeline, which cuts through the heart of the Wet’suwet’en yintah (meaning “territory”) and stands to contaminate their primary water source. The film is an infuriating project to observe, with its blunt rendering of state violence and the Canadian oil picture. But Yintah keeps a firm grasp on the colonial residue extant in these communities, especially the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and the sexual violence enabled by “man camps,” the pipeline construction residences. The film carefully frames dozens of red dresses hung in nature to represent MMIW, a radical act of rightful emplacement which makes the RCMP squirm. Yintah is rife with these moments of institutional discomfort, censuring a nefarious, profit-driven regime and their “machines that crawl.” The result is an assured, gripping communiqué of whose histories we inhabit on and off screen, and how to ensure their preservation.

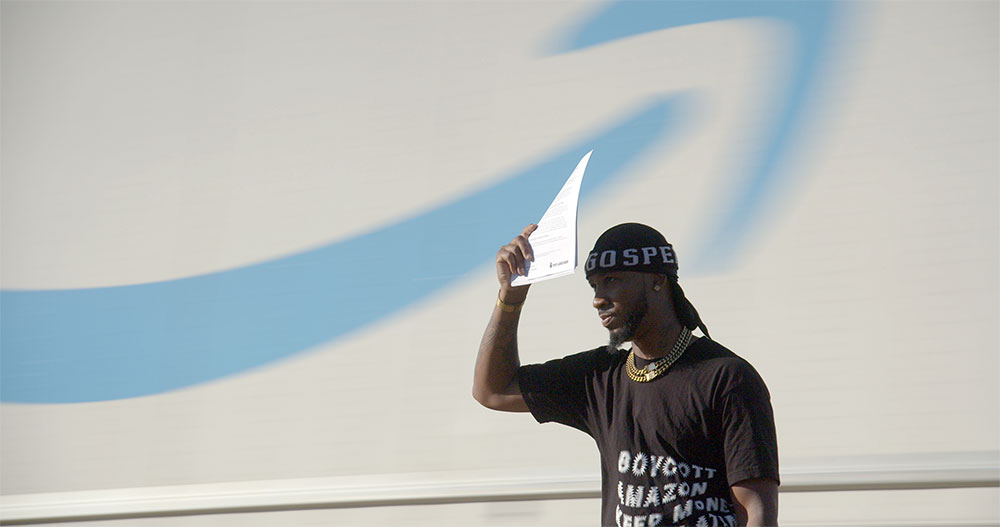

Collective action against dehumanizing conditions also runs through Brett Story and Stephen Maing’s scintillating Union (2024), which follows the inception of the grassroots Amazon Labor Union at the JFK8 warehouse in Staten Island. The ALU was the first recognized union of Amazon workers, led by Chris Smalls, who was fired in 2020 for organizing a walkout to protest unsafe working conditions in the wake of COVID-19. Beginning with a lumbering shot of a gargantuan freight ship, Union crystalizes Amazon’s scope and what the burgeoning union would be up against—to put things into perspective, we learn that Amazon has a 150% turnover rate, replacing nearly 100% of its workers every six months. The organizing efforts are shot beautifully by Maing and Martin Dicicco, who capture the isolating, highly technologized environment of the warehouse against the warm, familial quality of the union booth, which is just beyond the facility’s reach. As one of the producers mentioned in the Q&A, the film’s visual language sought to identify “the gap between what is seen and known and what is unknown but sensed.” The structural coercion on the part of Amazon is expected, but the intra-union squabbling—about leadership, dues, strategy—becomes a necessary hurdle in building solidarity.

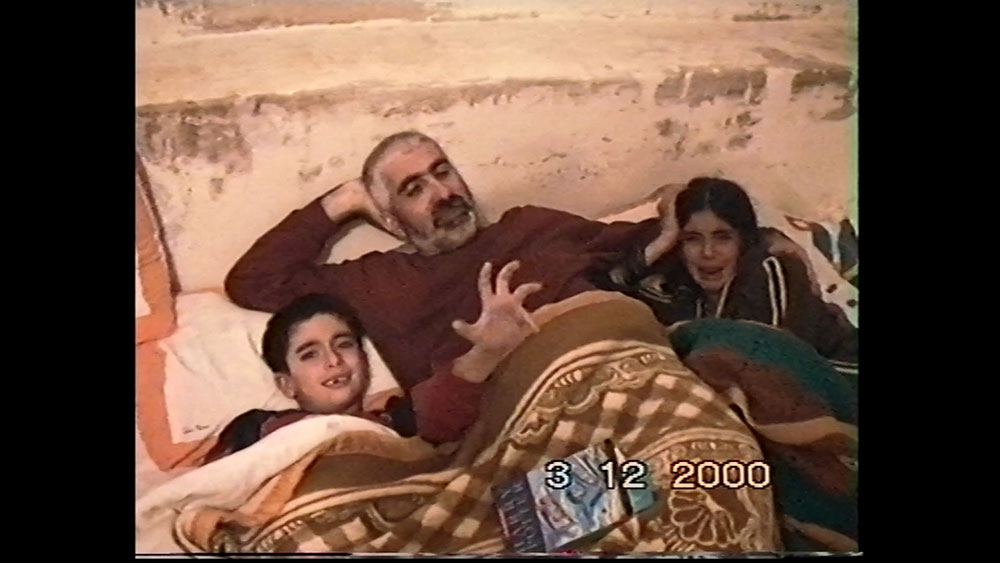

Two films that played the festival circuit in late 2023, Three Promises (2023, pictured at top) and 1489 (2023), proved to be the most heart-wrenching pair in my schedule—if not for the ferociously personal levels of access given to audiences, for the knowledge that the wars depicted in the films are ongoing. Yousef Srouji’s Three Promises is composed almost entirely of home movies from Beit Jala, Palestine during Israel’s retaliation to the Second Intifada from 2000-2005. The footage is captured by Srouji’s mother, Suha, who diligently observes the modes of violence deployed by Israeli forces: sound bombs, explosives, jets, rifles. Srouji’s curation of the footage—Christmas festivities into state violence, cowering in basements into images of fig trees, streams, and almond leaves—ensures the audience is met with sentiments of Palestinian joy as much as forced displacement and brutality. Contending with such an archive (kept hidden from Srouji and his older sister for decades) is an immense undertaking, but bringing it into a world where images of the ongoing extermination of Gazans are at our fingertips becomes an explicit call to action.

The title of Shoghakat Vardanyan’s debut 1489 refers to the anonymous number assigned to the “body of an individual missing in action.” In this case, the director’s brother Soghomon Vardanyan, a 21-year-old student, composer, and pianist who was nearing the end of his mandatory military service when the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War between Azerbaijan and Armenia flared up again in September 2020. The film’s content is didactically spare, often handheld auto-portraiture of Vardanyan phoning the designated “dead and injured” line and praying with her parents. In these impossible moments, Vardanyan manages to configure beautiful shot compositions and sound design, with the mic picking up the slapping wind, static humming, and distant dogs barking, a prolonged clangor which intensifies an already severe viewing experience. That unencumbered access in the Ragtag Cinema screening room (which seated maybe two dozen) moved into a joint sob when the camera revealed Soghomon’s bones and Vardanyan’s parents clutching and smelling them. If there is one film in particular to seek out from this already impressive slate, it is 1489. I found myself especially sentimental realizing that, on my way to the theater, I saw the filmmaker crossing the street as a car began to slowly turn into her lane. A panicked volunteer shouted for her to move. When she didn’t flinch, the volunteer turned to me and muttered, “She should’ve been more scared.”