Our dispatch of the 2025 True/False Film Festival comes courtesy of Nicolas Rapold and Saffron Maeve, who sampled the festival’s diverse slate of documentaries and offered their thoughts regarding its highlights.

Nicolas Rapold

This year, strangers at True/False kept asking whether it was my first time at the festival. I took that as a good sign—I didn't look jaded?—but in fact I'd gone several times. That includes the collector’s edition of 2021, a remote hybrid dubbed Teleported, which I also wrote about as part of a duo for Screen Slate. Typically enough, my favorites from the 2025 edition came from vastly different flavors of documentary filmmaking, par for the course at the festival, which presented seven feature-length world premieres in addition to a curated selection from Sundance, IDFA, Berlin, and elsewhere. And while the festival could be a kind of bubble, there was also the perennial cognitive dissonance of state politics: for example (as ProPublica neatly summed up) four months after Missouri voted to legalize abortion, Republican lawmakers proposed a 100% tax credit for taxpayers who donated to crisis pregnancy centers, i.e., anti-abortion centers.

Turning to the films: leading the pack, to my eyes, was Resurrection (2024, pictured above) from Hu Sanshou, who received the festival’s annual True Vision award. (Past recipients include Rosine Mbakam, Dieudo Hamadi, Nuria Ibáñez Castañeda, and Bill and Turner Ross.) Hu looks homeward to record the particular upheaval in the Shanxi mountain village in 2022, when the Chinese government went ahead with building a highway straight through it. As diggers and drillers muck about the sloping landscape, villagers must hurry to exhume and relocate the remains of their ancestors from graves and tombs. They dig up and assemble skeletons by hand, and in ad hoc processions, carry the deceased like reverse-pallbearers to new places of rest. Throughout we watch the casual banter of workers and onlookers, who have seen a lot over the years; a cherubic kid who drops by only underlines how the school-age population is dwindling. Hu is affiliated with the Memory Project, which gathers oral histories relating to the cataclysms of China’s 20th century (like the Great Famine or the Cultural Revolution), and his film’s masterstroke is to show a biographical card for each burial that features recollections by a relative and by villagers, and a charcoal-like sketch. These one-line remembrances are brief but hugely evocative as they pluck details of work and marriage, as well as impressions, in note-like form: farmers, metal-workers, decent, handy, irritable, sickly, “People said he was a capitalist.” Pushing back on the looming demand of these enforced excavations, Hu shows the lyricism in a nighttime send-off with firecrackers and chants, expressing community-wide feeling but also inducing viewers to reflect on how we remember the departed. A programming bonus: True Vision award-winners are invited to select a film to screen, and Hu’s choice meant I watched Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993) in 35mm one fine Sunday morning.

One world premiere at True/False I’d been anticipating was A Body to Live In (2025), having seen the filmmaker’s bracing account of a conflicted family homecoming North by Current (2021). Angelo Madsen’s layered look at Fakir Musafar did not disappoint (born Roland Loomis in 1930!), following the artist (born in 1930!) across decades of explorations in gender, body modification, syncretic spirituality, and relationships. In photos of himself as a teenager, Loomis at first suggests a precocious figure out of a Kenneth Anger film. Working through stills, 16mm, and video, Madsen follows this steadfast explorer through intermingled alternative cultures, with a key flashpoint being the “Modern Primitives” movement headlined in the punk magazine Re/Search. Part alt-cultural timeline, part essay on communal support, drawing on what looks like both personal and broadcast footage, and ethereally scored by Madsen, the film is an open-minded portrait of an iconoclast that serves to illuminate entire communities, while also noting the audacity of Fakir’s borrowings (cue Native Americans on a talk show calmly objecting to his attempts at appropriating Sun Dance ceremonies). It’s almost too much to summarize in passing here (or to digest on one viewing), and the film comes to have a visceral impact thanks to Fakir’s body-modification rituals (probably the most extensive in documentary since Kirby Dick’s Sick, 1997).

I approached WTO/99 (2025) with a bit more trepidation, as a found-footage movie from a period I remember (also on the heels of the disappointingly shallow Time Bomb Y2K, coincidentally seen at True/False). The director, Ian Bell, chronicles the several-day protests around the 1999 World Trade Organization summit in Seattle through an on-the-ground mix of independent and establishment media as well as some police camera footage. Clustering around a few blocks downtown, the documentary portrays the parallel movements and multiple generations staking out battle lines—environmental activists, labor unions, farmers, and many unaffiliated individuals simply pushed beyond a breaking point—and traces the inexorable slide of the police and National Guard into tear-gas and other strong-arm tactics, despite initial claims by police leadership. The presentist tendency in the choice of off-street archival (hello, Bernie, Roger Stone, and Trump 2000 campaign webpage) doesn’t spoil the import of the event as a landmark in anti-globalization activism and awareness, but also as an evident lesson for police suppression of same. Despite a scattered look-ahead ending, some might be frustrated by the choice to dwell in the moment—emphasizing the grappling for control of the image and message of the events to the world at large—rather than step back for studied analysis. But without false triumphalism, the approach well dramatizes for another generation how defiance and independence always seem to surprise the ruling order, no matter how much their policies also make such resistance inevitable.

Finally, Macu Machin’s lovely debut feature The Undergrowth (2024) visits with three sisters in a woodsy corner of the Canary Islands with almond trees and brambles. Carmen, who has heartbreakingly pleading eyes, lives alone in a dim house where huge pots in the kitchen evoke family times past; the more pointed Elsa arrives with Maura (whom she takes care of) to sort out inheritance of the land. So much of the film entails sitting around with them, speaking or not, even sleeping—a serenely shadowy portraiture, with bric-a-brac and sprawling legal papers adding touches of still life. Their familiarity, the tensions and the love in the air, instantly transport you back at any given moment to imagining the trio as girls in the same house. The Undergrowth only gathers strength as it goes, until a nearby volcano incredibly seems to express all that courses beneath the surface. In its stubborn modesty and then surging intensity, it’s the sort of singular film that one feels lucky to come across at a festival, and then pass along like a secret you want everyone to know.

Saffron Maeve

Maybe it’s a Midwestern birthright, but I’m very endeared to Missouri. Columbia, where True/False is held annually, is coaxial to Topeka, where I was born, and has the sort of cozy charm one expects from a university town. Full of giggling undergrads and stalwart filmgoers, the few blocks that insulate the festival were aglow with intrigue, and far friendlier than my slushy Toronto. (Multiple attendees apologized to me as a Canadian on the behalf of their government, for instance. I did not have the heart to tell them how similarly troubled the North really is.)

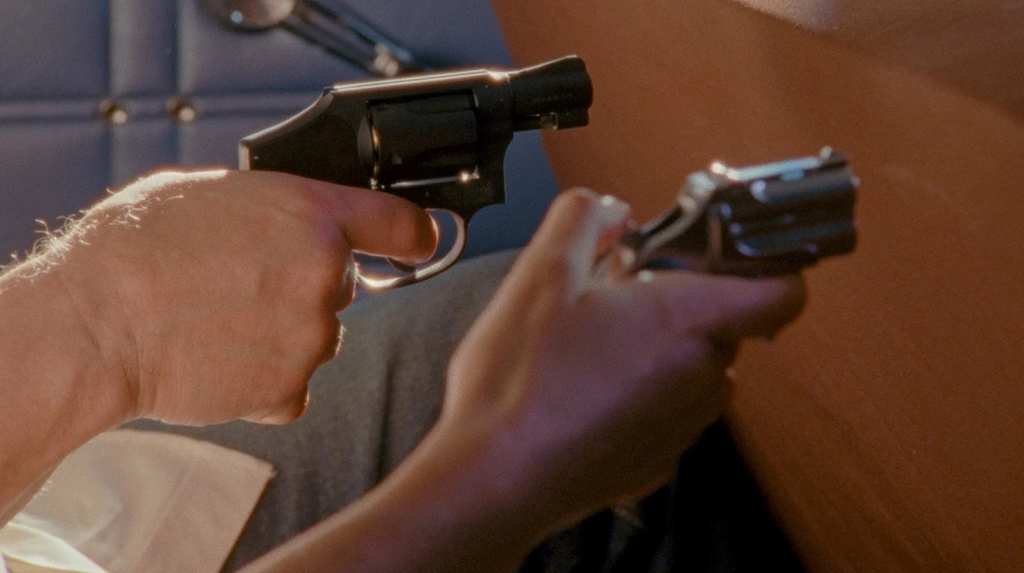

First on the docket was the British filmmaker and multimedia artist Charlie Shackleton’s curious Sundance player Zodiac Killer Project (2025), made at the margins of an aborted adaptation of Lyndon E. Lafferty’s book The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge. Lafferty’s book—a veritable tome of vigilantism—follows his journey as a retired California beat cop who swore that he knew the identity of the Zodiac Killer and alleged a wider cover up when local law enforcement refused to heed his warnings—and, of course, was mocked in the face of Robert Graysmith’s commercially favoured 1986 non-fiction book Zodiac. When the rights apparently fell through during pre-production in Vallejo, Shackleton reoriented his approach to this “failure” with a wryly confronting offshoot of the would-be film: a project comprising long takes of the intended filming locations, featuring the director’s shot-by-shot narration of what would have happened in the scene.

Zodiac Killer Project has an essayistic finesse, lifting and citing sections from popular true crime fare while both deriding their obviousness and establishing the syntax of this bloated genre as something to be toyed with or broken open. It should surprise nobody that Shackleton is a former critic. He is altogether empathetic to Lafferty’s literature while also communicating the drudgery of adaptation—it’s a sort of ballet of legalities, with the director cautiously paraphrasing the text alongside public record of the killer. (At times, you hear him rifling through the pages of The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up in voice-over, a coy and ghostly synthesis of this phantom project.) The two driving failures here—Lafferty’s inability to capture who he believed to be the killer and Shackleton’s inability to fully limn this story—create an authorial alignment that divests from the predictable gruesomeness of the Zodiac Killer. A very strong aperitif.

An apparent mainstay of Midwestern film festivals is the resignification of the American pastoral, as seen in Sasha Wortzel’s River of Grass (2025) and Brittany Shyne’s Seeds (2025). River of Grass, also a world premiere, takes up the Everglades (“the liquid heart of Florida”) as a site of excavation and shared memory, combining archival footage of writer and conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas with latter-day Mikasuki activists and disgruntled Floridians. The Everglades have been dredged, drained, and impounded for profit, and annual sugarcane burning releases noxious pollutants which disproportionately affect the surrounding Black communities. Each subject, Wortzel included, shares their professional, spiritual, and/or emotional ties to the wetland, after which point lyrical text flashes on screen: “the air thick like velvet,” “this series of miasmic swamps…” Though I found this text pedantic at first, I eventually considered it an elegy independent of the many disparate characters—an abiding flow of words to fill out the gaps in their sentiments. In this sense, River of Grass is affectionately cluttered, with the community’s competing methodologies given the latitude to freely coexist.

A monochrome portrait of Black farmers in the American South, Seeds observes the intimacies of various farming families in the face of systemic disregard. As we learn, Black farmers owned some 16 million acres of land in 1910, cut back to less than two million acres today; a fact worsened by the Department of Agriculture’s dwindling subsidies and clear racial biases. The film examines the generational tangle of land ownership in the United States while also presenting this acreage as an alternate infrastructure in which children can flourish. Shot by Shyne in her directorial debut, Seeds boasts remarkably tender sights and sounds, like whole pecans rattling around a bucket; the whir of an automated pea sheller; fluorescent grey cigarette cherries poised against the landscape. The film has a fittingly laboured pace—I joked to a friend that it was loitering with intent for its long but gratifying sequences—but is so gently arranged, one can only feel impressed. I found myself extremely moved by a scene where a community member suffers a stroke and a farmer leaves a bunch of fresh radishes on her doorstep.

Carrying out this same impulse of nature and intervention (on far weirder terms) is John Lilly and the Earth Coincidence Control Office (2025), co-directed by Michael Almereyda and Courtney Stephens. Coolly narrated by Chloë Sevigny, this film traces the stochastic life of the American physician and psychoanalyst John C. Lilly, most commonly credited with the invention of the sensory deprivation tank and his contentious LSD experiments on dolphins. The film shapes Lilly into a compelling spectacle, detailing his earnest efforts at interspecies communication and highlighting cinematic tributes like Altered States (1980) inspired by him. We encounter his early Cold War-era aspirations of a “Brain TV” and “panoramic thinking” which eludes human language, body, and ego, as well as his (NASA-funded) home/seaside lab in St. Thomas, FL, where he cohabited with dolphins in a shallowly flooded bungalow. (Surely an inane point of reference, but I was transported back to my 2006 Barbie Hot Tub Party Bus, which had an inch or two of water sloshing around the plastic base at all times.) It would be an impossible task to match the cetacean freak of such a figure, and the filmmakers nobly don’t seem to try; sometimes the archives speak well enough for themselves, especially in Sevigny’s cadence.

Aggregated ancestries made up a sizeable portion of this year’s slate, with Misha Vallejo Prut’s Light Memories (2024), about the director’s efforts to connect with his late grandfather through an archive of his images found in Riobamba, Ecuador, and Bassam Mortada’s Abo Zaabal 89 (2024), about the director’s activist father whose confinement in an Egyptian prison corrupted his family life. Both are fine films, and best watched in close succession, though the standout for me was Maxime Jean-Baptiste’s Kouté Vwa (2024). Combining archival footage with scripted scenes, Kouté Vwa follows Melrick Diomar, a 13-year-old living in Stains, France, who is spending the summer with his grandmother in his hometown of Cayenne, French Guiana. During Melrick’s visit, an interest in percussion reveals a shared attachment with his late uncle, Lucas, a beloved drummer and DJ (and cousin of Jean-Baptiste) who was fatally stabbed in 2012. Melrick’s slow-growing exposure to brutality connotes something about the extant colonial violence that continues to stir in French Guiana, though Jean-Baptiste maintains an affectionate eye on the Diomar family and their daily rituals in the face of this enormous grief. Building toward a group musical performance in Lucas’s honor, the film is a deft act of preservation and communal memory that features music from the local collective Mayouri Tchô Nèg, and, in one extremely touching sequence set on a roadside at dusk, a movement from Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders, and the London Symphony Orchestra. The screening of Kouté Vwa I attended was held in a small Presbyterian church, a setting that seemed to tease out the spectrality and remission that lines this project—perhaps best exemplified by church bells aligning perfectly with the film’s opening credits.