Scene Report is a new series in which Screen Slate contributors consider a recent cinematic event in retrospect.

"I wonder if the two of you can talk about growing old." The prompt, posed by the curator La Frances Hui to the filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang and the actor Lee Kang-sheng, takes a long time to translate.

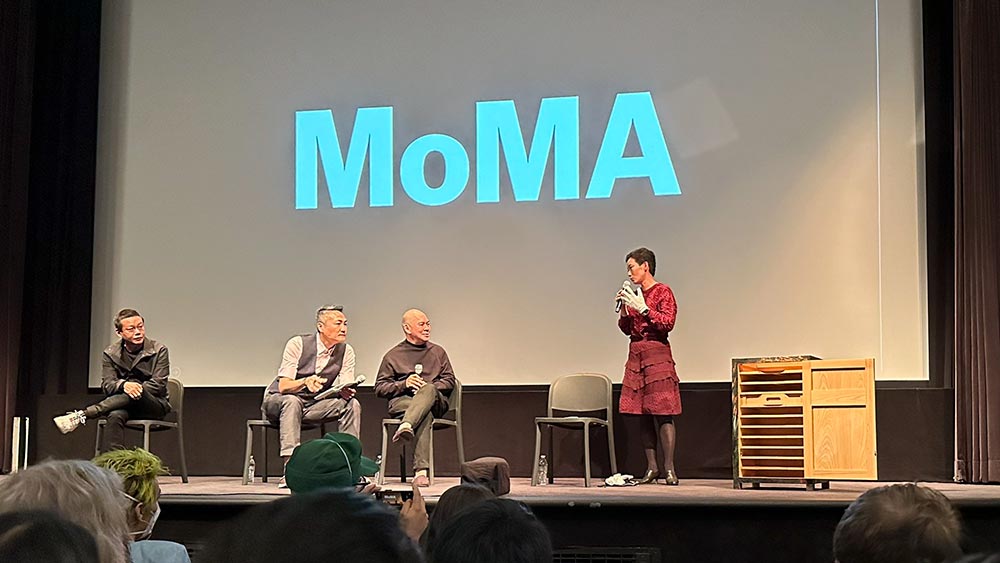

On a recent evening, the larger of the Museum of Modern Art's two cinemas is full nearly to capacity after a screening of Face (2009). The film is a sort of commingling of Tsai's cinematic universe with François Truffaut's, set in the bowels of the Louvre, which co-financed the production. The blank-check commission made for a fabulously liberated indulgence; Tsai joked in his introductory comments that he no longer knows how to interpret the film, which bursts with oblique symbols, extravagant costumes, and musical numbers. It also planted the seed for how the filmmaker has come to produce his work, largely within the institutions of the art world rather than on what remains of the arthouse cinema model.

The occasion for Tsai and Lee's visit to New York—their first in ten years—and of the retrospective of their work is MoMA's acquisition of an editioned 35mm print of Face, complete with bespoke wooden storage cabinet, displayed on stage beside the conversants. Its exterior is painted by Tsai with a scene from the film, in which Mathieu Amalric gives Lee head in the bushes of the Tuileries Garden. The director has become fond of analogizing his films to paintings, and in the past several years he has taken up the brush himself. Face is the last of his films to be shot on celluloid, and the resulting object has been entrusted to an appropriate reliquary.

Lee appears in all of Tsai's feature films. The two have been working together for 30 years, since Tsai saw Lee outside a video arcade in Taipei and cast him in Rebels of the Neon God (1992). The director is ten years the actor's senior, though to see them now you might guess the opposite. On stage, Tsai, at 65, is glowing, monklike, cherubic, animatedly answering questions at some length, delighting the largely Mandarin-speaking audience with observations the rest of us will wait eagerly to hear spoken in English by Vincent (Tzu-Wen) Cheng, Tsai's frequent translator. Lee, seated apart from the others, hunches over his crossed legs and clenches his jaw, visibly fighting jetlag. At 54, he looks like an aged boy.

In answer to the moderator’s question about growing old, Tsai speaks about seeing the work of time on the bodies of his actors, not his own. As Tsai considers in stark terms the deteriorating physical health and appearance of Lee, the actor is mostly stoic, though he adds to the creases of his face a thin smile at certain moments. When it is Lee's turn to speak, his smile broadens. He points us toward recent films by other directors in which he appears nude, proving "there is still a market" for his physique.

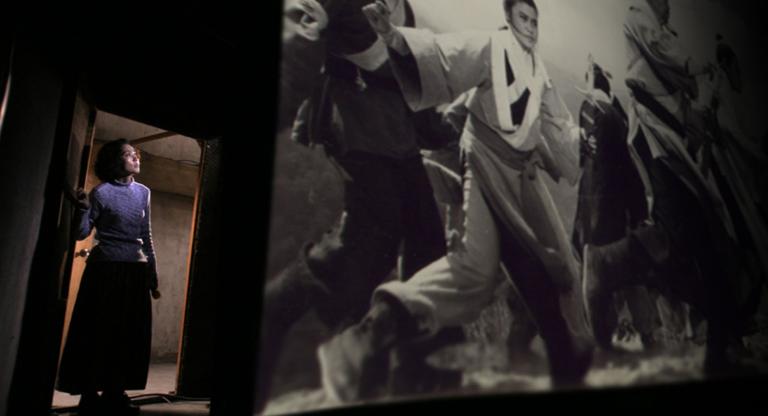

In fact, Lee appears nude in Days (2020), Tsai's most recent feature, while prone and waiting for an erotic massage. Throughout the almost wordless film, Lee seeks treatment for chronic neck pain, a real-life condition previously dramatized in The River (1997). On the street, wearing a neck brace, he supports his temple with an index finger, the camera pacing him by a few strides. He has become more anonymous, we realize, no longer the kind of man who necessarily turns your head. He walks a little unsteadily, on legs that may not be the same length; what was once a jaunty stride is now a stagger. His hair is still thick, though flecked with grays. His face has grown puffy, like a fresh welt. In his youth, he was striking for his insouciance, his sharp but distant mien. Such qualities play more dully in the form of a middle-aged man, and that tarnished luster is now the object of Tsai's interest.

Lee seems to embarrass Tsai by revealing that the first choice for Laetitia Casta's role in Face was Maggie Cheung, who was unavailable at the time—apparently because she had fallen in love. Maybe it is the wolfishness the leading man evokes when speaking about his scene partner that makes the director uncomfortable. The two, who share a home together outside of Taipei, are every bit like an old couple, fondly devoted to each other and merciless in mixed company. Like many couples, there is an imbalance at the center of their relationship: Lee cannot entirely return the ardor that Tsai must feel for his muse.

The two have long characterized their personal relationship as familial, though that too is freighted with meaning in light of a filmography in which incest is a prominent theme. To see them together, I caught myself thinking of Dorian Gray and Basil Hallward, an older admirer who paints the portrait on which the marks of Dorian's sinful life will show. Oscar Wilde's book is an allegory of illicit sexuality, a Gothic horror in which the monster is the author himself, guilty of everything for which he condemns Dorian: only sodomy, of course. The comparison doesn’t really work—Lee ages as usual while his likeness on the painted cabinet remains unchanged—but, in some sense, Lee's filmic image becomes a ledger of Tsai’s accumulated desires and indignities, the director’s avatar and whipping boy.

"He almost served as a mirror," Tsai has said of working with Lee on Days. "We are more and more alike the more I look at him." Asked in that interview about pandemic isolation, Tsai does speak about growing old himself: "The longing for love changes as the result of the aging process. Now there's not so much of the yearning. Now there's the fear that I might lose the ability to love with age."

“Tsai Ming-liang: In Dialogue with Time, Memory, and Self” continues through November 13 at the Museum of Modern Art.

Photos by Niels Joaquin.