Gilles Charalambos is a pioneer of Colombian video art who began his career experimenting with television back in the 1970s. He is also an art historian who studied in Moscow during the 1980s and took the strenuous task of writing a great book, Aproximaciones a una historia del videoarte en Colombia (2019), about the history of Colombian video art from 1976 to 2000. His work on video art’s history is not simply a collection of empirical facts. While reading his book, I thought of Jacques Derrida and Walter Benjamin since Charalambos shares Derrida’s sensibility for history as an activity that grants equal significance to absence and not simply as the linear recounting of established records. What has been forgotten, excluded, and repressed in official historical narratives about Colombian video art appears in Charalambos’s work. With Benjamin, he shares a taste for constellations: the amalgamation of disparate ideas and historical phenomena to form an image of what video means for him—a medium linked to mystery, phantasmagoria, cosmology, ritual, and divinity.

On November 11, we had a two-hour conversation over Zoom that felt like a great piece of performance art. I never thought a humble video-call could elicit an aesthetic experience, but my conversation with Charalambos transformed how I think about video—the most pervasive medium in contemporary society and, ironically, the medium that perhaps receives the least critical attention. This interview has been translated into English and edited for clarity.

Andrea Avidad: Your email signature caught my eye during our first exchanges. You call yourself an ex-exartist, not just an ex-artist. This repetition of the prefix ex can result in its paradoxical erasure, and thus, the figure of the artist persists. Can you tell me about the connotations of this self-designation?

Gilles Charalambos: Yes, the negation performed by each repeated prefix results in a paradoxical affirmation of the artist. Beyond that temporal or spatial logic, the double use of the prefix ex in my signature has connotations that relate to a shift in my thought about the paradigms of art and a critique of ideological concepts that frame what is commonly understood as art—institutional art.

It's been 25 years since I started calling myself an ex-exartist. Back then, I lived an experience that profoundly changed my views about art. While exhibiting my work in the Dominican Republic, I had the chance to also visit Haiti, where I witnessed voodoo rituals that lasted over 12 hours. In that experience, I discovered a very rich field of aesthetic values that I considered, and still consider to be, much superior to those I had learned about in more official spaces like museums until then.

In the voodoo rituals I discovered a type of live art, even if the aesthetic dimensions of these practices remain unacknowledged by archeologists and anthropologists. They don't even dare to call it art because the art institutions haven't recognized it as art. But what I saw in the voodoo rituals in the Caribbean was a total work of art much superior to and more advanced than the one theorized by [Richard] Wagner in a Western context. In the Haitian voodoo ritual, which for me is a total work of art, there is no differentiation between public and maker, artwork and exhibition. There is no difference between metaphysical states or between art forms like music, dancing, or painting. Not even a sensorial differentiation between smell, sight, and hearing. There is no difference between technology and metaphysics. It's a total work of art.

After that experience, I became more and more annoyed by the institutionalization and commercialization of art, and the official figure of the artist. I had always rejected the ideologies of spaces such as the gallery and commercial art in general. I had always been interested in doing avant-garde, even marginal work, or “underground art,” as New Yorkers would say. But my opposition toward the institutional art world grew greater back then. I saw artists become more and more subjugated to the conditions imposed by institutions, curators, and critics—all motivated by money. It was no longer just unacceptable for me to participate in that world, it was unbearable. So, I became an ex-exartist.

And ex also suggests being outside oneself, as in éxtasis [ecstasy]. If the signature identifies me, it is an identification that makes me go outside or beyond my own self in the work.

AA: You describe the etymology of the word “video” in your book Aproximaciones a una historia del video arte en Colombia. The term comes from the Latin verb video, which means “I see,” conjugated in the first person. So, the term denotes a subjectivized act of seeing. How did you become interested in the specificities of the medium of video and its mediated forms of seeing?

GC: There are inherent qualities to the medium of video that have always seduced me, for example, the transmission of the image in real-time. I became interested in video because it gave me access to the electronic transmission of the image. I had been fascinated with television from a very early age. I started experimenting with the apparatus, altering and distorting images because I have always been interested in noise.

This ability to transmit and distort the image in real-time has a very different optical logic than the one followed by the specular image, mirror, and mirrored image. That aesthetic and conceptual space necessarily results in narcissism, in a gaze that always returns the image to oneself. Something that profoundly bothers me about the conventions of cinema and video art is the position of the camera—placed at eye level. Conventional cinema makes the camera coincide with the human eye. The eye of the camera is analogized to the human eye and the human head. I wanted to break free from this kind of subjectivization of the camera as soon as possible. In that sense, in my work, I feel closer to the kind of de-subjectivized gaze offered by Stan Brakhage’s work in the 1960s. A gaze without position, a position-less eye. I am not interested in representation, narrative, or psychology. I am interested in abstraction.

Another theme I have always been very interested in is electricity. I've researched it historically from the point-of-view of its iconology. I’m passionate about studying the various Gods of electricity, including the Christian God, which is not Christ but Yahweh, and, of course, Zeus, and, in the Americas, the God Tláloc. This primordial interest in electricity made me interested in video. For me, video is the art of electricity. Of course, in the 1980s, video became an electronic art, but it was my interest in electricity that first sparked my interest in video. As I mentioned, I first began experimenting with the distortion of the televisual image. Then, my father bought a small video camera in the 1970s and that gave me the first access to experimentation with video.

AA: Let's talk about noise. Here, I am thinking of opposing accounts of noise. For example, there is the one offered by cybernetics and information theory, which sees noise as the disturbance of a signal, or as an unwanted transgression that must be eliminated. But then there is also someone like the philosopher Michel Serres who offers an account of noise where noise is not a destructive force, but a necessary condition for creative innovation. For Serres, noise underlies all order and meaning. What role does noise play in your work?

GC: I have always been interested in noise at an epistemological level. In my work, noise is not only visual distortion. I employ noise as an interference in many different modes. There is electronic interference—electronic noise—which has its own specific characteristics. But noise is also a concept. A paradox is noise and interference. If we analogize logic to signal, then the paradox is noise.

Noise and distortion are my two main stylistic elements. The specificity of any process resides in the noise produced in and by that process, because the type of noise produced in a specific process cannot be produced in a different process. For example, the noise produced by electronic distortions in video cannot be produced in cinema. You can mimic it or make a reference to it, but you cannot produce this kind of noise in cinema or in any other medium.

So, this is the most essential characteristic of noise for me. It is specific to a process, to a medium. I am interested in specificity. Noise is very rich and I have experimented a lot with it, as form and idea. Of course, if you consider it from the ideological views that privilege communication and reception, noise gets a bad reputation. In communication theory, as you said, noise is a problem. If you look at it from that framework, noise is hard to accept. But suppose you disprivilege reception and communication as principal values. In that case, you see that noise is inevitable—noise is part of nature, noise is part of reality.

Then, there is another problem with noise: the vulgarization of noise, its banalization as the glitch. The glitch in video is not noise, but a vulgar aestheticization. Noise cannot be treated as an aestheticization. Noise is not part of the beauty salon. The glitch belongs in the beauty salon, already predigested and accepted. This vulgarization of noise testifies to the overall banalization of the medium of video.

But noise, beyond its vulgar aestheticization, is usually seen as a negativity. And like all negativities, like death, noise is negated. Problems are negated; that is to say, they are forgotten and marginalized. Noise is rejected mainly because of the importance given to the ideology of reception. Under this ideology, everything must be made for the sake of communication. Artists think their work must communicate. It's an imperative. Everything is made in the name of communication. This impulse is also related to the obsession with production and productivity, which is seen as a quantitative issue, not a qualitative one.

But, for me, the work of art is not necessarily communicative. I am not interested in reception, because we cannot simply say that a video contains or is the artwork itself. All artworks are performative in the sense that they must be made and that making is the artistic act. The performative process is also the artwork. The process, which is very noisy, is also the artwork.

AA: You start the introduction to your book with an epigraph by Jean-Luc Godard that reads: “The historian's job is to accurately describe what has never happened.” This seems to be particularly resonant with the history of video art in Colombia. It seems to me that this is a history full of absences.

GC: Yes, there is a complex problem of historical absences and absent histories. First, there is an absence that refers to the lack of interest in video art by historians and critics alike, at least in Colombia. Then there is another problem, another absence. There is no shared mythology about Colombian video art. This absence transforms video art into phantasmagoria. I had to write, or even hallucinate, Colombian video art’s mythology. Let me tell you about two mythologies about Colombian video art I wrote about in my book.

For me, the greatest Colombian artist is the poet León de Greiff, who also did radio art since the 1950s. Back in 1955, he was interviewed by the Argentine art critic Marta Traba on live television. During the interview, she noticed that his fly was open and let him know. But instead of doing something about it, de Greiff continued acting like she had said nothing. For me, that was a performance, in the sense of performance art. And for me, that is the beginning of video art in Colombia.

I end my book by including another mythology about disappearance… Or another form of absence—the absence of an image. In one of the exhibition rooms at the Luis Ángel Arango Library in Bogotá, a surveillance video system was framing a painting of San Francisco by [Francisco de] Zurbarán. A security guard had just seen that the painting had been moved to a different room through the security video system. The painting had been moved, but its image persisted in the surveillance system. Everyone got terrified, from security people to admin people. The painting continued being there, on the surveillance screen, like a ghost. It was an “error” of the camera. But, for me, this moment is also part of a mythology about Colombian video art. The mythology of Colombian video art is a mythology of phantasmagoria. There are so many other absences and phantasmagorias in art history.

For me, the French did not invent photography in the 19th century. The indigenous peoples of Venezuela and Colombia experimented with recording images well before the French did—recording images on leaves, for example. They would also place their hands or other objects on their bodies and let the body get burnt so that images would be recorded on the surface of the body. This is photography. Same thing with abstract art. It does not begin in the 20th century. Abstract art is much, much, much, older. It's archaic. In South America, we have indigenous art, which is eminently abstract and geometrical. However, since such art wasn't made by institutionalized artists or artists who can be identified or recognized as artists, it became phantasmagoria.

But let's go back to video. It's evident that in Colombia, a deep conservatism—a moral, political, and even aesthetic conservatism—linked to the interests of a specific socioeconomic class made not just indigenous art disappear, but also video art, mainly because video art is immaterial. Same thing with television. They didn't, and still don't, recognize television as art. I don't mean TV, which is the commercial use of television, but television as such. Even though someone like Nam June Paik made artwork for television and is one of the top 10 artists of the 20th century, television is still not recognized as art. Another phantasmagoria. Another paradox. And so many absences.

AA: Tell me a little about the difficulties that video artists faced in Colombia from the 1970s to the 1980s. How did the political and social contexts impact the development of Colombian video art back then?

GC: I am not interested in thematizing social or political, not even psychological, dimensions or conditions in my artworks. But, yes, Colombia's extreme political and social realities impacted the work of video artists in those decades. First, there was, and still is, the problem of extreme inequality and poverty. The economic access to equipment was a problem. Access to equipment and post-production studios was very difficult. Not even the universities had their own equipment. Since many artists didn't have access to video, there was very little formal experimentation with the medium. They weren’t familiar with video technology and its possibilities because they didn’t know the technology.

It was conventional video art, focused on description, reference, and anecdote. The psychological as theme was also dominant. It was all about personal problems, about showing someone's point- of-view. The political dominates as the central theme now. Well, it has been doing so for a long time, really. In Colombia, politics has a very noticeable impact on all aspects of life. So, in Colombian video art, you will find that the central theme tends to be violence.

Almost all Colombian artistic work references violence, both sociopolitical and socioeconomic violence. This bores me. Artists are not sociologists, economists, or politicians. So, artists who make references to violence don't make any meaningful contribution because they cannot offer any political solution. Their work is just descriptive. Of course, I don't blame those artists. The social injustices in Colombia are terrible.

But the problem is that people ultimately gloat about poverty. To go back to your previous point about the etymology of video, the “I see,” and of narcissism, there is a self-identification with violence and poverty. Psychologically, it is a form of narcissism; sociologically, it is part of conservatism. Now, there are some cases where you can find originality in Colombian video art. There is a specific kind of gaze—an ironic gaze. In many images, you will find more than one meaning or sense; the images have a double or even triple sense. It's part of a sense of humor, a dark humor which is very Colombian.

AA: Video art only gained institutional recognition in Colombia in the 1990s, which is very late. How did this happen?

GC: The recognition of video art in Colombia was a product of the constant comparison of Colombian art with international art. The institutional recognition of video art as art in Colombia wasn't an endogenous phenomenon but an exogenous one. The presence and recognition of video art in the 1990s as art was too strong at an international level, so critics and curators had to accept video art as art here in Colombia. I don't think that the critics and curators really understood video art. They were not even really interested in video art. But they had to recognize it as art at that point.

Even after this late recognition, the problem was, and is, that video art has never found a space to be exhibited in. Galleries and museums don’t know how to exhibit video art. Museums don’t know if they should exhibit video art as a projection, as if it were cinema, or if they should put the works in a televisor, on top of a pedestal. So, people just walk by without seeing the art works. It is like that scene in Godard’s Bande à part [1964], where the characters run through the Louvre without seeing the art works. To find a public for video art is very difficult. I have found few interested in paying attention to video art in a 50-year career.

But there was something positive about this late recognition of Colombian video art as art. Because video art was at the fringes of recognition for so long, video artists didn't have to follow predetermined styles, forms, or concepts found in conventional art forms. That was my case. I experimented a lot with the technology, with form and concept, which, for me, cannot be differentiated from one another. I am a pre-structuralist. For me, form also means idea and concept. Form is not just the result of an operative process; a form is a concept too that gets integrated with the operations of a process and experimentations with the specific qualities of a technology.

AA: I don’t want to end this conversation without asking you about life and death: is video art dead?

GC: [Laughs] What is funny to me is that contemporary artists, regardless of the medium they might use—be it cinema, be it theater, or painting—consume video every day, and still, they don’t work with the medium of video. Video is the most common, the most present medium in the world. Yet, people don’t really experiment with it. Everyone says that video art is dead, but you know what? For me, it has always been dead. Video art is a zombie.

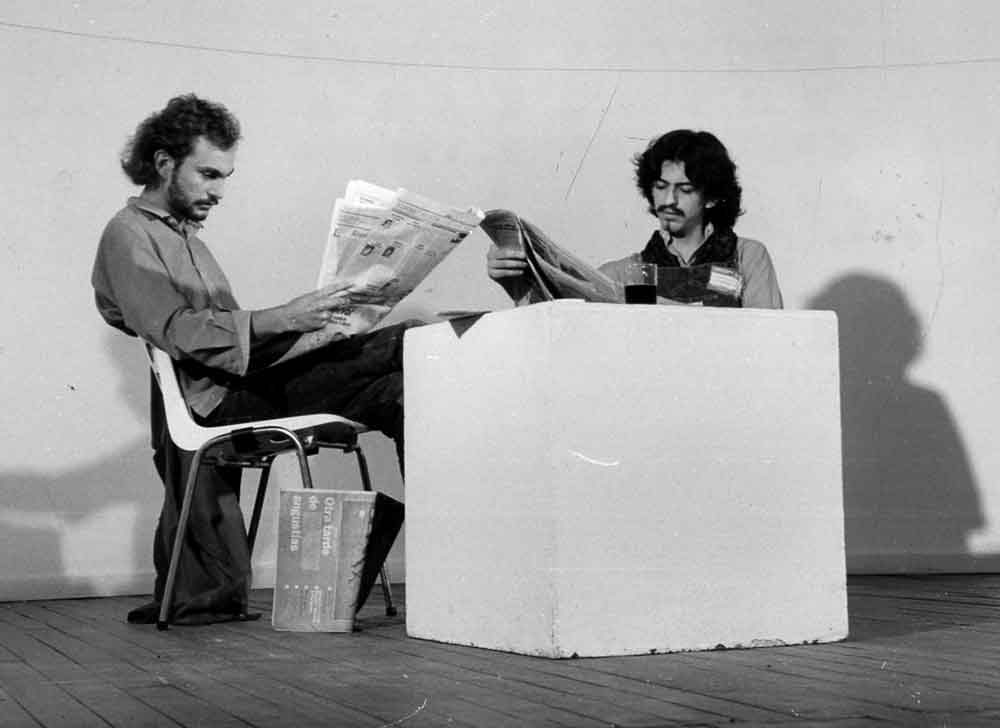

X and CÁLCULOS EXTÁTICOS screen this evening, December 5, and on December 10, at Anthology Film Archives as part of “‘A MEDIUM IS BORN’: A SHORT HISTORY OF EARLY COLOMBIAN VIDEO ART.” This screening will also feature work by Sandra Llano-Mejía, Karen Lamassonne, and Véronique Mondéjar.