The news in 2019 that the Paris Theater was closing was a cruel blow to New York filmgoers, following the 2018 demise of the Lincoln Plaza Cinemas, which shuttered less than a month after the death of its founder, Dan Talbot. The Ziegfeld was already gone; the Paris was the last single-screen theater standing. In a twist that confirmed the new landscape of film exhibition, it was a streaming company—Netflix—that saved the theater, reopening it with a successful run of Marriage Story. I was hired in early 2020 to program and help manage the theater; weeks later, the entire exhibition business shut down. In the spring of 2021, with a much-needed facelift (including new seats, a new screen, and new equipment including dual 35mm-70mm projectors), the Paris reopened. A 35mm showing of Dog Day Afternoon (1975) was the city’s first post-pandemic repertory screening. Hundreds of films later, I’m leaving my position, on to other programming projects. I’m glad to be presenting Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962)—in 35mm, with an introduction by Molly Haskell—which opened at the Paris almost 60 years ago. It plays there this evening in memorial tribute to both Godard and its luminous star, Anna Karina.

“The Paris Theatre will present tomorrow the face of a woman trying to find herself in a world of men” announced the September 22, 1963, New York Times ad, with the simple picture of Anna Karina, her face framed by her now-famous Louise Brooks bob. My Life to Live (Vivre sa vie), Godard’s fourth feature film, was only his second film to be released in the U.S., after Breathless (1960). It was distributed internationally by Pathé, the production and distribution company that built the Paris Theater in 1948 on a prime piece of real estate between the Plaza Hotel and Bergdorf Goodman as its glamorous New York flagship (it serves the same function for Netflix today). The Paris thrived for 70 years, buoyed in its heyday by incredibly long-running hits such as Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (52 weeks in 1968 and 1969), the Bridget Bardot vehicle And God Created Woman (38 weeks in 1956), the French romantic comedy Cousin Cousine (41 weeks in 1975 and 1976), and the all-time champ, Claude Lelouch’s syrupy A Man and a Woman (65 weeks in 1966 and 1967). In fact, Vivre sa vie was the first new movie to show at the Paris in over a year, following the 53-week run of Divorce, Italian Style (1961). (The Godard film only lasted three weeks.) From the 1970s on, the Paris became the house theater for James Ivory and Ismail Merchant (Room with a View, 1985; Remains of the Day, 1993), and was the preferred venue for the legendary Michael Barker, who has opened more films at the Paris than any other distributor (Call Me By Your Name, 2017; Howards End, 1992). (The theater was also the preferred New York venue for the disgraced Harvey Weinstein.) The formula for success at the Paris over the years was a continental blend of sophistication and sex.

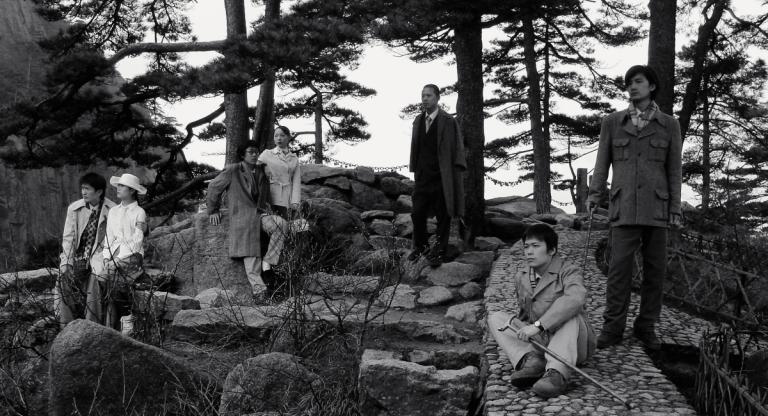

Vivre sa vie was not the first international hit with a prostitute as protagonist (Nights of Cabiria, 1957; Mamma Roma, 1962; and When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, 1960, preceded it), but it brought a cool observational detachment to its potentially lurid narrative. The film is divided into twelve Brechtian tableaus, each preceded by silent-film style intertitles (“8: AFTERNOONS – MONEY – WASHBASINS – PLEASURE – HOTELS”). The jazzy jump cuts of À bout de souffle are replaced by deadpan minimalism, long conversation scenes, and the crystalline purity of Raoul Coutard’s black-and-white images; the action and impulsive behavior is replaced by introspection and ideas.

The most thoughtful newspaper review was found not in the New York Times, but the New York Post. Archer Winsten, who called the film “a winner,” praised Godard for his stylistic inventions, “giving the thing a documentary quality of scene and structure, dry, unsentimental, informative, intellectually probing,” and then going on to speculate about the film’s fascinating tension between emotion and ideas. “It would be a cold film if it weren’t for something else that Godard’s wife brings to the role. She is a beautiful girl, and, without putting on an act, she manages to convey the inner hurt and painful doubts that beset her. The effect is at once coldly objective and deeply moving. To put it another way, Godard is objective and the viewer becomes subjective, which is as it should be.”

The Village Voice offered two interesting responses. Jonas Mekas, in his “Movie Journal” column, praised it as “the most beautiful film playing in town,” while admitting to being bothered that “the film seems to me too well and too carefully planned, with no holes for air, for unexpectedness, too studied.” He found Godard and Karina too hung up on “consciousness, logic, thinking,” proclaiming that “it is time to descend into the lower regions, the intuitive mind, the Burroughs mind, the Henry Miller mind, the Jack Smith mind . . . the Dionysian mind.”

Yet to Andrew Sarris, the apparent coldness of Godard’s style, and the film’s seemingly abrupt ending, would stand the test of time. “Time seems to work for Godard, and in time the apparent coldness of My Life to Live will be perceived more clearly as admirably formal control of the wildest romanticism in cinema today. My Life to Live, by the very violence of the reactions it evokes, is the most profoundly modern film of the year.”

Vivre sa vie screens this evening, December 22, at the Paris Theater in 35mm. The screening will be introduced by the critic Molly Haskell.

Since it’s end-of-the-year list time, I’ll sign off from the Paris with this list:

Top 10 Movies that Opened in the U.S. at the Paris Theater (in chronological order). (A complete list of films that played theatrically at the Paris can be found here.)

Casque D’Or, (1952, dir. Jacques Becker)

Othello, (1955, dir. Orson Welles)

My Life to Live, (1962, dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

Viridiana, (1961, dir. Luis Buñuel)

Deep End, (1970, dir. Jerzy Skolimowski)

Howards End, (1992, dir. James Ivory)

Metropolitan, (1990, dir. Whit Stillman)

The Flight of the Red Balloon, (2007, dir. Hou Hsiao-Hsien)

Call Me By Your Name, (2017, dir. Luca Guadagino)

The Power of the Dog, (2021, dir. Jane Campion)