Ken Loach, the beloved chronicler of proletarian life and resistance, is retiring after having directed 28 features and over two dozen BBC teleplays over the last six decades. His films have consistently merged politics and drama, presenting the lives of everyday people and their struggles under capitalism with compassion and honesty. They have also consistently provoked major discussion. His 1966 teleplay, Cathy Come Home, exposed 12 million viewers to the plight of homelessness and spurred discussion in Parliament for years to come. More recently, 2016’s I, Daniel Blake, which won Loach his second Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, prompted a similar nationwide debate in Britain about the country’s callous and convoluted welfare system.

Both his documentaries and fiction films—many of which are collaborations with screenwriting partner Paul Laverty—represent a history of the English working class over the last half-century. In the current era of film production, in which it’s practically impossible to imagine a filmmaker having a continuous platform to create working class stories with an unapologetically left-wing perspective, Loach’s oeuvre remains remarkable.

Film Forum is currently hosting a two-week, 21-film retrospective of the prolific British director’s work, in addition to his latest and self-proclaimed final feature: The Old Oak (2023). If it is indeed his final film, The Old Oak is a powerful one with which to leave us: a portrait of the solidarity that can be built between segments of the working class who may not initially see their commonality; in this case, the long-time residents of an impoverished mining town and the Syrian refugees who arrive there. Like many of Loach’s films, it demonstrates that the personal and the political are inseparable, and how today’s battles are in conversation with struggles for collective liberation throughout history.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Ken Loach to discuss The Old Oak, the themes he’s explored throughout his career, and why working class life is at the heart of drama.

Stephanie Monohan: If this does wind up being your final feature, it feels like it ends on a more hopeful, future-looking note than some of your other films. I was wondering if you felt that way about it?

Ken Loach: Yes, I think Paul [Laverty] and I both did. These are such dark times and we need to identify hope. And I think it’s important that hope is not wishful thinking; it’s not sending a letter to Father Christmas and posting it under the chimney. It has to be the real possibility of change for the better and a pathway to do it. And I think the hope is genuine: it is the strength of solidarity for the working class. The working class has the power to turn the switch off and stop what’s going on. Understanding that strength and being prepared to confront those who are exploiting them—exploiting the world’s resources, pursuing an aggressive foreign policy that leads to wars—that’s our hope. Our only hope is solidarity, finding unity and understanding that the interests that we have are in common, and that our interests are in common with refugees and working class people from other countries, not with those who exploit and who, at the moment, seem to have the power.

SM: How did you land on the particular location and communities that you featured in The Old Oak?

KL: Well, I’d say the North East is special. It’s built on old industries—shipbuilding, steel and coal mining—which all closed within a few decades of each other toward the end of the last century. Mining villages are not part of larger towns. The pit, with the wheel, the shaft, and everything, is often in the countryside, and miners’ houses are clustered around the outside. Maybe a few thousand—a few hundred, sometimes—terraced houses and that’s it. It’s an image of one industry and the consequences of when that industry shuts down.

The defining moment that led to that was the [1984] Miners’ Strike and the victory by Margaret Thatcher. It was the same time as Reaganomics and the Chicago School of Economics—the rise of neoliberalism as a project. That defeat of the miners, the strongest union that was, was the moment when neoliberalism was allowed to get a grip. We are now suffering the consequences of it, so it’s a pivotal moment.

The mining villages are a classic image of deprivation due to one industry’s failure. Shops closed down, community facilities shut down, infrastructure shut down, churches closed, schools closed, sports—all the great things the miners had, that they had built up over generations, most of them disappeared. It left people angry and embittered, but there was still the tradition of solidarity that the miners had as miners. Because your life depends on the person next to you, solidarity is part of the job.

During the strike, they became internationalists. Miners’ wives, people who had never spoken in public before, traveled across Europe making speeches to big crowds. It was the best of times and the worst of times. It was an extraordinary period and they lost. The value of labor went down and we live with the consequences. But that’s why we chose it, because the image of the mining village is so precise.

SM: You spoke to this a bit, but one thing that the film made me think a lot about in terms of your wider body of work is how intertwined the past is with the present. The character of Yara learns about the Miners’ Strike and communal dinners that the families used to have, and it sparks her idea about how to bring the British townspeople and the Syrian refugees together—it’s this building of intergenerational and interracial solidarity through history. Could you talk about how history informs your characters? It seems to come from a Marxist, materialist perspective…

KL: Maybe that’s me and Paul, but the reality is that the history is very present. The strike was 40 years ago. For the people who lived through it, and their sons and daughters, it’s not nostalgia; it’s something very alive in people’s memories and their children’s inherited memory. The rage against the Labour Party, the party of the working class, is another element that causes great anger. The party walked away from the strike. Other trade union leaders walked away from it and accepted defeat. So a sense of pride mixed with a sense of being betrayed… They’re living in the middle of that memory. The consequence of their defeat, which is the destruction of their community, is all around them. It’s very present.

SM: In revisiting a lot of your films, it seems almost like they speak to one another. The strike that is central to the town in The Old Oak is something you explore in more detail in Which Side Are You On? [1984]. In Jimmy’s Hall [2014] we see life after the Irish Civil War, which is a huge part of The Wind That Shakes the Barley [2006]. It feels like a historical continuum. Do you see your filmography as a larger political project in and of itself?

KL: Paul is central to this because all the ideas come from conversations between us—messages and chats, news that catches our attention, and football of course. It’s an ongoing friendship and comradeship—it comes out of that. And of course, one film begs the question of, “Now, what happens?” We did the film I, Daniel Blake, which is about the difficulty of getting social security payments that you’re due because the government bureaucracy makes it so difficult. And that led to, “Well, what about people who are actually in work? The gig economy, casual labor, working all hours. What does that do to families?” And then, working on that film [Sorry We Missed You, 2019], you can’t be working in that area without seeing the image of the deserted mining villages.

SM: Something I really appreciate is how your films capture so much about labor and working, and about how working life and family life are so intertwined. How do you go about approaching these topics in a way that feels so humane in how they all intersect?

KL: Thanks for spotting it, because in your dreams you try to do that. Being realistic, you have to make an effort to cut it out. It’s like humor. Humor is just part of who we are, our daily life. It makes you smile even in dark times. Daft things happen as well as tragic things.

If you’re trying to look at the consequences of the gig economy, where nobody knows when they’re going to be at home and when they’re away while they’re trying to bring up kids, how do you manage that? Well, you’ve got to manage it because you need the money and that’s the job. Half the women in the country are dealing with things like that, maybe more. It’s central to our life now. What is significant are the choices people have. And the poorer you are, the fewer choices you have, the more imperatives you have—the busier your life is just dealing with the essentials. That’s a kind of clear, essential truth, and that’s where the drama is. That’s where the daily struggle is.

Sweet Sixteen [2002] is full of choices. My Name Is Joe [1998] is full of choices. In My Name Is Joe he’s not working, he’s a recovering alcoholic, and he’s got to raise money to get a lad out of trouble.The only way he can raise money is to do a drive carrying drugs for a drug dealer. And of course, the woman he’s beginning to have a tentative relationship with is a social worker. She sees the toll of drugs, is dealing with it every day, and asks, “How can he do that?” And he says, “What choice do I got? What would you do?” These are agonizing choices and very real. And that’s the essence of drama, isn’t it? Every working class street is people making choices like this. George Bernard Shaw called it “middle-class morality.” It’s all very well that you can afford your morality of what’s right and wrong. When you get down there and have to confront the choices the poorest of the working class have to face, your morality will be rather changed. I think dealing with all that is the essence of drama and if you can get it right, that’s pure gold isn’t it?

A Ken Loach retrospective runs through May 2 at Film Forum. The Old Oak is now playing in arthouse theaters nationwide.

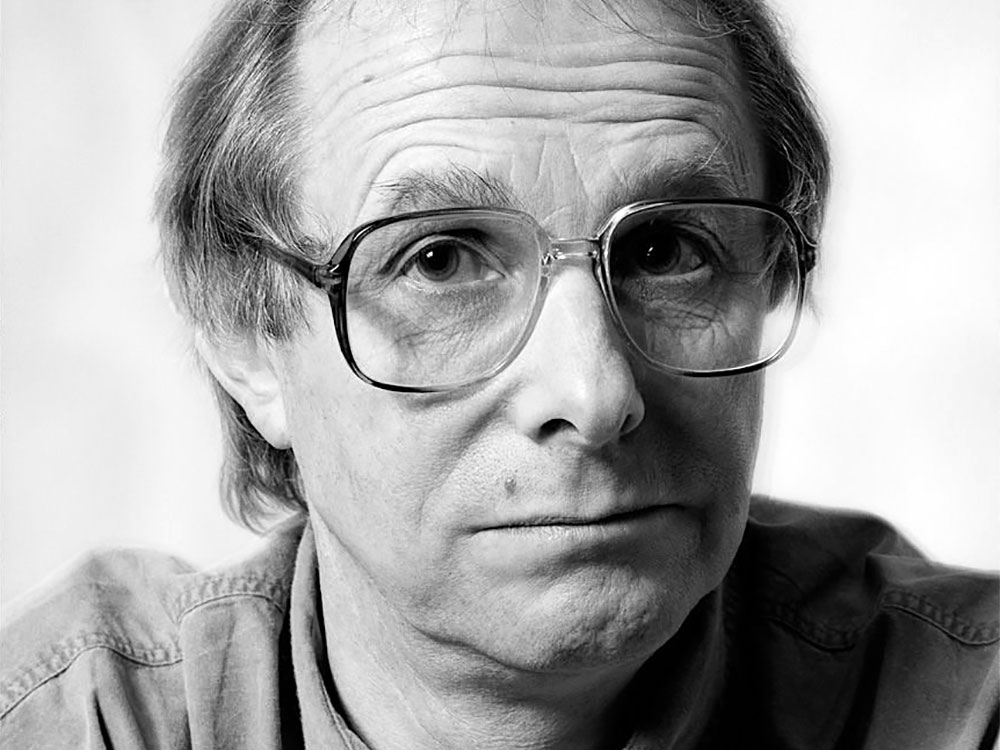

Ken Loach photo by Robin Holland.