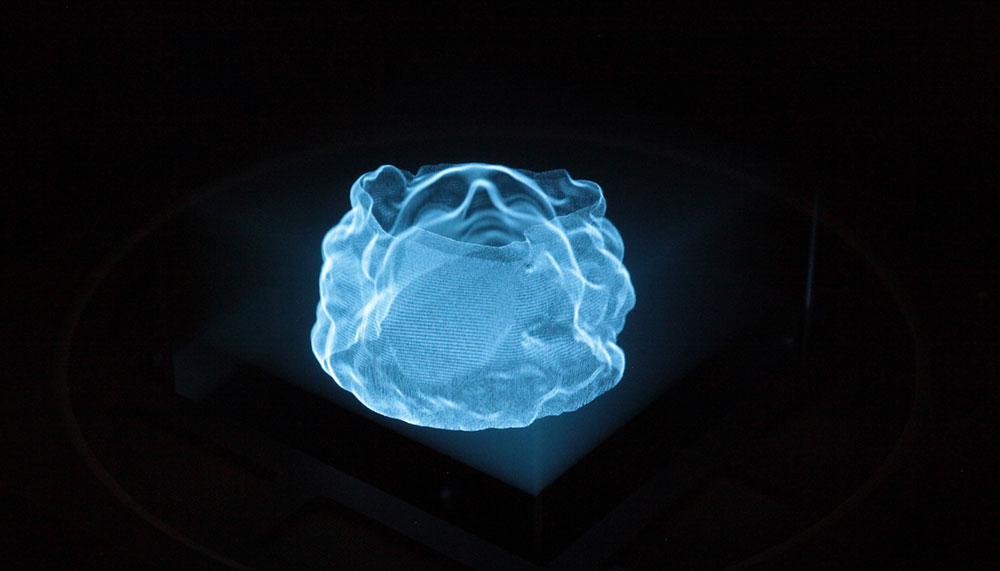

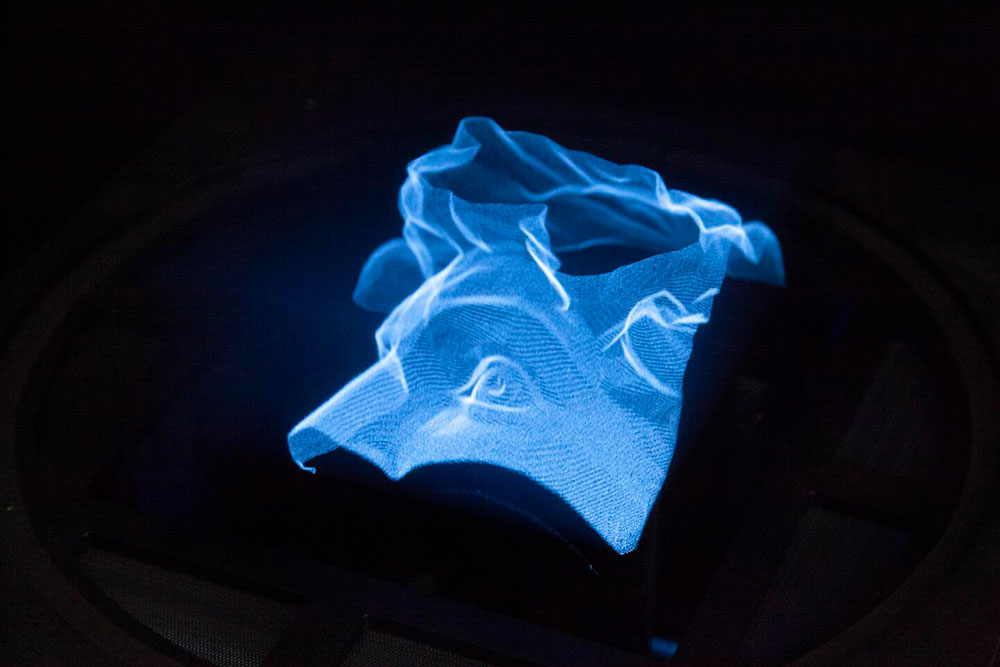

David Levine’s latest work, Dissolution (2022), is a movie in a box. Or rather, it is a movie holographically projected in a 20-minute, 6x6-inch volume of time and space by a device called the Voxon VX1. “Where other 3D display technologies use multiple views of a scene to create a stereoscopic view,” Voxon’s website reads, “[this] technology physically builds a model of the scene using millions of points of light.”The Voxon—which Levine was able to access with Harvard research funds—wasn’t originally made to screen movies, but working with a team of animators and sound engineers, Levine made Dissolution using motion-capture technology and programming in Unity.

Vox, the protagonist and narrator, is cursed to forever roam a world that Levine has built to describe the cultural sector from deep inside its bowels. In this realm, not so different from our own, art collectors leave corpses in their pools and stash art in their basement freeports; the newcomer ancient heroes Museos and Deep Throat stage a mythic encounter in a subterranean museum parking lot; octopuses mine crypto with their tentacles. All these gorgeous scenes that seem to hover in space are served with a multi-track monologue, but not the didactic kind one might expect from contemporary video art. Revelation, Vox says, is “not my job. My job is to make you forget.” Dissolution is the last in a trilogy of exhibitions in which a protagonist, always named VOX, wrestles with passing as or becoming art. In the first two, Bystanders and Some of the People, All of the Time, VOX was embodied by human performers; in Dissolution, the character has finally been sublimated into pure light.

Dissolution premiered in 2022 as part of the exhibition Fata Morgana at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. I met with Levine at his Bed-Stuy studio to watch the movie again prior to its U.S. premiere at the Museum of the Moving Image tomorrow. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Andreas Petrossiants: Can you tell me about the Voxon, which Alex Kitnick called “dangerously rudimentary” in a recent piece?

David Levine: Basically it works like film, but with a Z-axis. You’ve got a horizontal screen that flies up and down fifteen times per second. That’s what creates the illusion of height and volume. Because the screen moves on motorized springs, the whole thing sounds like a 16mm projector. And, because the screen is made of glass, you run the risk of slicing off a finger if you try to touch the image.

AP: It’s really tantalizing! It beckons touch.

DL: Yeah, the projector’s hidden in a custom-made black plinth, so that all you see when you walk into the darkened room is this sculptural image, floating above a pedestal, with a guardrail around it, like those used to protect a particularly valuable antiquity. Only in this case the valuable old thing you’re protecting is your fingers.

AP: The plinth also gives the piece an obviously sculptural element which inspires a more involved form of viewership than most video. It makes the dark room feel like its own kind of theater as you circle around this small, glowing movie. Was this approach to installation some kind of response to the conundrum of showing video art in the museum?

DL: Yes and no. I left theater because I hated that auditorium-style viewing angle. It felt too much like looking at painting, and I wanted a more sculptural encounter with performers—sort of like the minimalists’ impatience with painting—so I started doing performances in gallery spaces, where you could see them from all sides. And I never really got into making video for the same reasons—that restricted viewing angle just bothers me; it flattens things. But this projector let me have a sculptural encounter with video in a way I’d never seen before, so I opened up to it.

One thing you learn when you cross over into art from another discipline is that every discipline has its technologies and rituals of attention, and they’re highly refined. Auditoria are designed to make you watch and focus over time, and your immobility relative to what you’re watching is what allows you to pay attention to details and track the passage of narrative time—not to mention the ritual of everyone showing up at a fixed start time. But galleries are designed to induce a different kind of attention, and they’re a bad fit for anything other than contemplating paintings and sculpture. Like, when people turn galleries into reading rooms or screening rooms. The gesture itself registers as art; but these are less-than-ideal circumstances for reading ephemera or taking in movies.

So formally, Dissolution isn’t really a response to “video in the museum,” but more an outgrowth of my affinity for certain ways of encountering work. Content-wise, yeah, it’s definitely a response to the sententiousness of “video essays in museums.”

AP: In addition to questions of spectatorship and presentation, performance is really important for your work. You research modes of acting; the weird ideological girdles welding authenticity to personality; how performances function and reproduce on complex political terrains. In the case of Dissolution, you’re using a technology that was not meant to project artworks to speak directly to viewers.

DL: Yeah, this machine wasn’t really designed for a 20-minute movie. Once we worked out that it would have to be designed in the Unity game engine, we had the challenge of figuring out how to play back a twenty-minute movie with synced audio on a machine that has very little playback memory. The Unity build would take like thirty minutes to load, and you’d lose audio sync as you dropped frames. Eliot Mitchell, our Technical Director, communicated with Voxon, who developed a codec to make the playback less memory-intensive and more reliable, as well as a few new tools to augment their Unity plug-in.

Once those tools became workable, it became a lot like directing a film. We were making this during Covid, so the animators would create scenes on desktop emulators, they’d send them to me for playback in 3-D on the Voxon, I’d send them notes with timecode, we’d refine, they’d send them back, and so on and so forth. For the volumetric capture sequences, we worked with a Greenpoint company called Evercoast, who were amazing and cut us a deep discount.

But it takes a while to figure out what works and what doesn’t in this format, which is a totally different way of making and watching a movie. The lead animator, Andrea Merkx, developed this wild visual language that really maxed out what the machine could do in unexpected ways. Like you begin with “Uhhhh, let’s just make this 3-D head talk,” and you wind up with tours of Versailles by way of King’s Quest and Sunset Boulevard.

AP: Following those teasers, can you briefly introduce the screenplay?

DL: It’s Against Nature meets Tron. Basically, some C-lister who’d been living a terrible life, spending too much time on their phone, bad values, longing for death; something reaches a nadir, and they find themselves digitized, trapped in this machine, as art. This situation has benefits and drawbacks, and the monologue is them trying to work it out.

AP: There are some great ways that the multiple audio tracks argue with each other as part of that self-reflection. At one point, Vox keeps trying to say “Finally, I am content” (stress on the second syllable, as in peaceful), but the other track interrupts: content (stress on the first, as in media). Or “I object,” a Bartleby-style protest, which becomes “I, object,” resigned acceptance of reification.

DL: I wrote it at a time when I felt like I was glitching a lot myself. Like, the machine that I am was becoming decrepit, sputtering. And these idiotic puns kept going through my head. The scenario—this person who feels like they’re dissolving, they’re maybe a little paranoid, suddenly cast into this space they don’t understand, with rules and shadowy authority figures—let me enact my own paranoia and fear of collapse.

AP: This is coupled with pop-culture incursions (e.g., Homer Simpson saying, “Man this place looks expensive,” from inside the art object), especially from video games, bringing 8-bit into 3-D, but also commenting, I think, on the transversality between the meme and the artwork, at least in how they are received today. Is that the idea?

DL: Ugghhhhh. No matter how fast you bail, art takes on aura like a leaky boat taking on water. I’m trying to displace it with my mental trash. I identify really strongly with how Daniel Lopatin talks about sampling retro detritus in a recent profile: “‘You think I like this shit? It’s garbage.’ But it’s the stuff of my life, whether I like it or not.”

But part of it is also wrestling with the myths of “political art,” and whether you can ever liberate the experience of art from the injustices it’s built on, or the architecture it’s experienced in. Like, if you actually decolonized a museum, it wouldn’t be a museum. With art, you either have to say “Fuck this whole thing” and walk away, or ask yourself why you’re so attached to an institution defined by exclusion and built on blood. And then you’re at a crossroads: Maybe all art is actually good for is escape and forgetting and denial. Is that good enough? Can you accept that? Would an experience of escape be valid on its own terms? Do you need to justify it any further, alongside other, more materially political commitments? Is that OK?

AP: Another question you told me guided the work is whether beauty is OK.

DL: It’s the same question. Visually, Voxon images are very beautiful because of the machine’s mechanism and also its limitations. It’s not like the cold, hard experience of VR. It sounds like film projection; the pixels have grain like film; it’s kinda low-res. My friend Gideon said that it’s “the most advanced thing the ’80s ever came up with in the present.” Dissolution emerges from those constraints: what the machine is capable of influenced the film’s plot and aesthetic and references, and the ’80s and early ’90s were the high era of lost-in-the-machine fantasies. So, on the one hand, you have this very sensuous Tron / Max Headroom aesthetic. On the other, you have my own anxieties about beauty, politics, and privilege. What you get in the end is a movie that’s toggling between them.

Brecht pretty much made how I think about things and gave me a deep suspicion of what he called merely “culinary” gestures. So, I’m not a “beauty” guy in my own practice. But then I was confronted with this machine that makes these images that totally hypnotized me, and I wanted to be hypnotized some more. But the Brechtian in me is saying “No, no, hypnosis bad. Verfremdung good.” So, I created this incredibly annoying narrator as a means of short-circuiting or jamming the hypnotic visual experience of the piece. I’m proud of the monologue, I think it has a point to make. But I think the first time you see it, you’re mostly blocking it out in favor of the visuals, learning how to see or watch this weird thing, and kinda wishing Vox would shut up.

AP: I find Vox more funny than annoying, tragic even. Speaking of that connection between the form of the work and the spectator, like a lot of expanded cinema, the content of the work is self-referential, especially to its form of production. Vox tells the viewer: “If this thing breaks, I’m fucked. If there’s a system update, I’m fucked. If they put this on the wireless network and Microsoft pushes an update, I’m fucked. I am very delicate.” Then they go on to describe the device and speak directly to museum conservators: “Just dust me off once in a while. And don’t put me in shows about technology. Or politics.” Here the monologue functions almost like a Fluxus score or conceptual artist contract prescribing its reception.

DL: I think of expanded cinema’s stakes as pretty noble, wrapped up in formal or political questions. And Fluxus’s self-referentiality often tends to be about drawing attention to the everyday; deliberately making pieces that are in some sense “too small” for the grandiosity of the museum, and then letting them loose and seeing what happens. But once Vox is turned into an artwork, they’re so obsessed with the circumstances of their own reception that their concerns start to seem really petty. Vox also seems convinced that by not letting you get a word in edgewise, it’s exerting sole control over its own reception, although clearly it’s haunted by the idea of its own fragility.

AP: Totally. One of the first times I watched this, I remember thinking that it was a movie about making movies, or making any art—more Singing in the Rain than Stan VanDerBeek. Is this your mega-comment on artmaking? Or a more specific dig at works that really believe?

DL: Nah, I love blockbusters. I love complicity. I love belief. My beef is with artworks that try to finesse their own complicity instead of diving in butt-first. There are a lot of ways to change the world. Seeing or making art isn’t one of them. It’s just too tainted by injustice and barbarism to ever get clean. But we all still pursue it. So what shall we do with that?

Dissolution premieres tomorrow, October 27, at the Museum of the Moving Image, and runs through March 1.