Well over half of Luchino Visconti’s fourteen features are literary adaptations, yet one would never mistake any of them for the work of another director. Of these, half are adaptations of novels by non-Italian writers—from the United States, Russia, Germany, Greece, and France—but in Visconti’s work, each contributes to Italian history. Tay Garnett’s adaptation of James M. Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946)—actually sanctioned by the author, unlike the Milanese aristocrat’s illegal adaptation and debut film, Ossessione (1943)—preserves the claustrophobic atmosphere of its pulp source material. But everything in Visconti’s adaptation, down to its elaborate crane shots, is done in grand style—its gestures bigger and its melodrama more exaggerated, repurposing the novel to describe the psychology of Italian society at the twilight of fascist rule. Visconti got his start in the film industry working as an assistant on the set of Jean Renoir’s Toni (1935), and the deep-focus composition of White Nights’s Venetian corridors point to the influence of the French filmmaker’s experiments with the sequence shot. Yet, their sensibilities could not be further apart. Even when dealing with a film the scale of The Rules of the Game (1939), Renoir manages to keep the material intimate. Visconti, adapting the smallest in size and in feeling of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novellas, tends toward the epic.

In relocating the setting from St. Petersburg to Venice, Visconti reasserts the historical and literary connection between the two cities, the former self-consciously constructed in the Italianate style as the latter’s copy. This aspect of St. Petersburg—echo and phantasm—helped shape Dostoevky’s writing, and his predilection for doubling is doubtless reflective of the city’s strange, imitative quality. The deep focus of the film’s cinematography invokes the dizzying proportions of both cities, constantly triangulating our view between different points of interest in the frame. The sense of postwar degradation, where desperation and poverty still prevail, looms over the film: homeless encampments are tucked into the corners of the frame under bridges or at the edge of city streets, while neon signs advertising Coca Cola hint at the domineering presence of American consumer culture after the war. All of this serves as the backdrop for the film’s central love triangle between Marcello Mastroianni and the woman with whom he spends four nights as she pines for her former lover, played by the French actor Jean Marais. (At a glance, as Visconti cuts back-and-forth between her memories, the two men even start to resemble one another). The stark contrast between Maria Schell, who plays the romantic and innocently callous Natalia, and Clara Calamai, as the dark-haired and cynical prostitute, only reinforces the former’s singularity in the narrator’s mind amid a world otherwise awash, in true Dostoeyvskian style, with doubles.

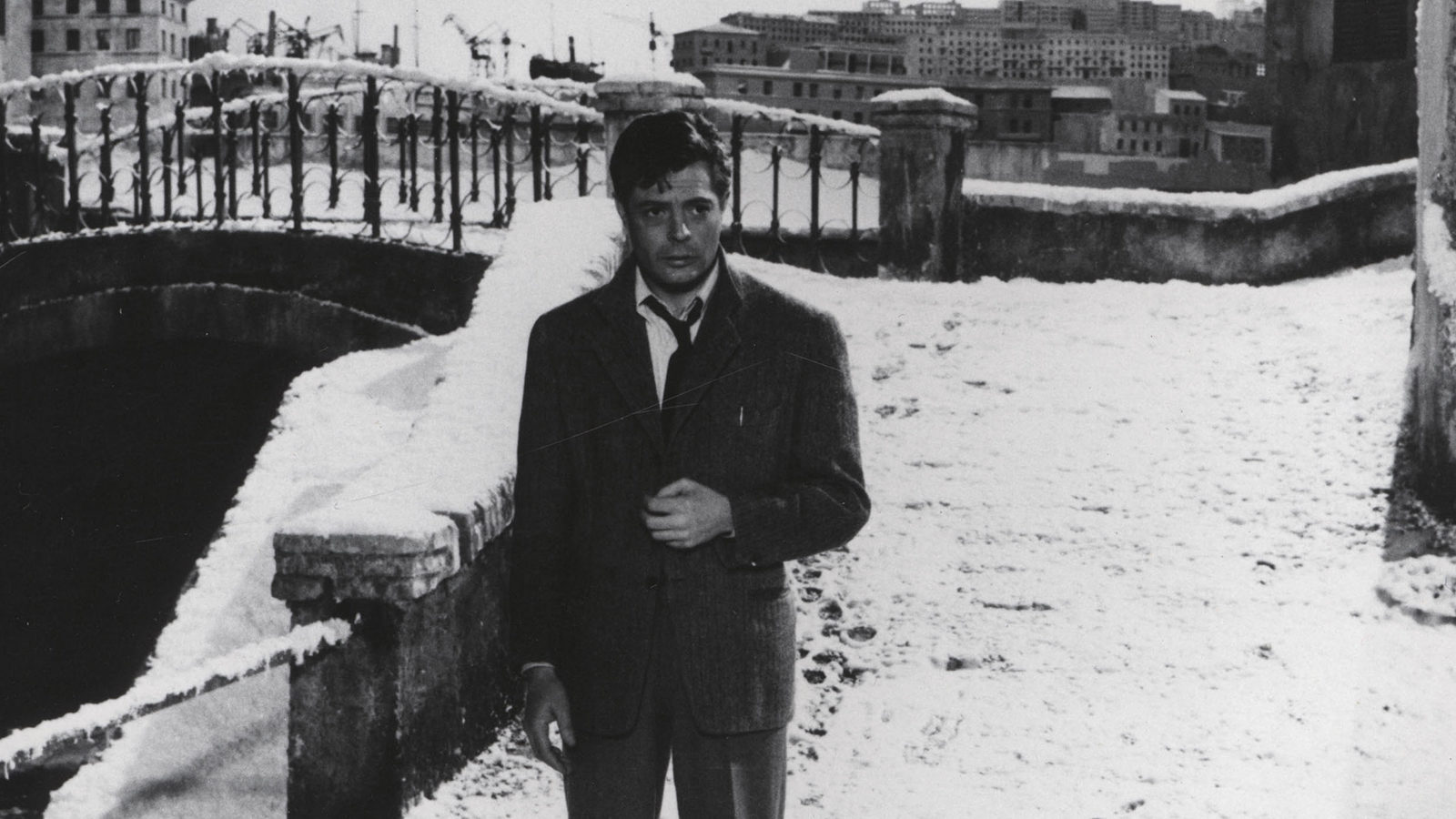

Mastroianni had already starred in films by a number of Italy’s most popular domestic filmmakers before taking the lead in Visconti’s film, among them Mario Monicelli, Mario Camerini, Luigi Comencini, Alessandro Blasetti, and Raffaello Matarazzo. Within a decade, he will have worked with three more of the country’s greatest filmmakers of the ‘50s generation: once with Michelangelo Antonioni and twice with both Federico Fellini and Vittorio De Sica. With his status as a smoldering, international icon still some years away, he maintains a boyish shyness as Dostoyevsky’s narrator, still awkward enough to provoke pity. Mastroianni’s performance is a delight in its unusualness and the dance scene alone makes the film a worthwhile watch.

White Nights screens tomorrow evening, December 12, and on December 18, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of the series “MoMA and Cinecittà Present: Marcello and Chiara Mastroianni, A Family Affair.”

White Nights also screens Sunday, December 15, at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive as part of "Marcello Mastroianni at 100."