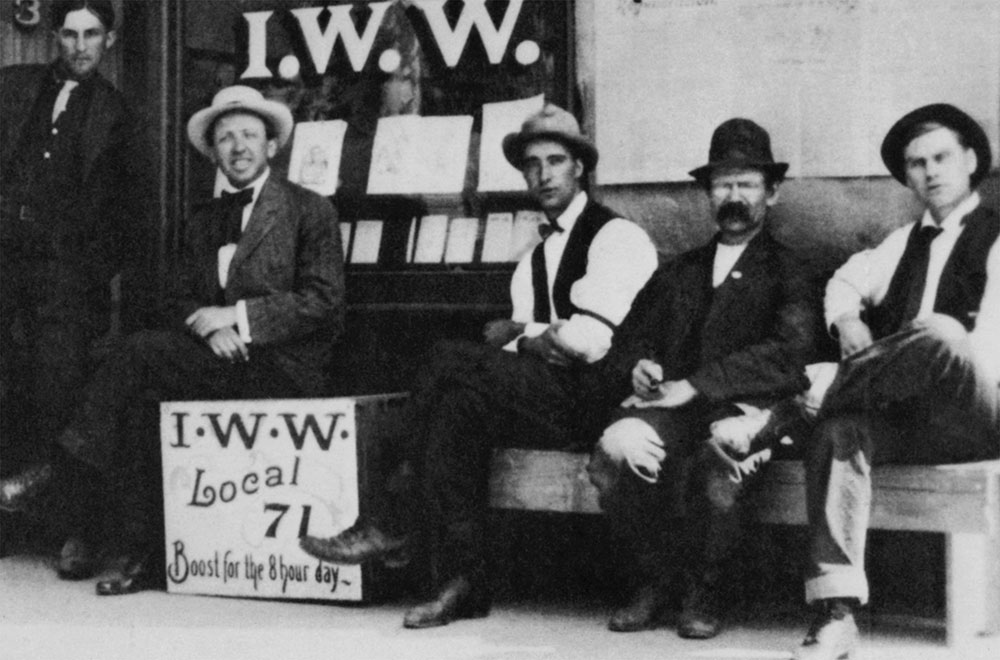

The Industrial Workers of the World was founded in 1905 as “One Big Union,” open to workers of all trades, man or woman, Black or white. It sought in particular to organize so-called “unskilled” workers, those who did not have a home in Samuel Gompers’s American Federation of Labor. For almost twenty years, the IWW was a radical force in the US, winning reduced hours, higher pay, and improved conditions by means of strike and occasionally sabotage, agitating always for worker ownership of the means of production and the abolishment of the wage system. The state marshaled its powers against the union in the form of brutality, raids, trials, deportations, and executions until, in 1924, the IWW was weak enough to be overwhelmed by a political schism. Some Wobblies, as they were known, went on to form the Congress of Industrial Organizations, now a part of the AFL-CIO.

In 1977, Deborah Shaffer and Stewart Bird began to interview those surviving members who had been with the IWW in the heady early years of the century. The resulting film, The Wobblies (1979), is an oral history of the union by its rank and file, including archival footage, voice actors, and even recorded selections from the “Little Red Songbook,” distributed to each member alongside their copy of the IWW constitution. The Wobblies has now been restored and re-released for a new generation to hear the union spoken and sung in its own words.

At the time of our conversation last week, Bird and Shaffer were anticipating a Q&A scheduled to follow a Friday, April 29, screening of the film at Metrograph, which was to also include Chris Smalls, president of the new Amazon Labor Union. On the day of the premiere, management at Metrograph canceled that evening’s event, apparently out of concerns that it would become a venue for criticism of the theater’s own unfair labor practices, which have become an open secret in New York’s film community. Last year Metrograph’s founding artistic director, Jake Perlin, programmer, Aliza Ma, and publicist, Michael Lieberman, all exited the theater. This March, a former Metrograph employee claimed that management fired its box office staff and offered money in exchange for signing NDAs.

I reached out to the filmmakers yesterday for comment but did not hear back. They shared a shared a statement with IndieWire, which read: “[W]e uphold the right of all workers to be guaranteed a safe working environment, fair wages, and to form a union to protect their common interests.” They thank Metrograph “for their courage in showing ‘The Wobblies,’” but “condemn their cowardice in canceling a Q&A with the filmmakers whose work on this historic documentary goes back 45 years.”

New York has lately seen a spate of union drives at cinemas, part of a nationwide wave of organizing in cultural institutions that began in the spring of 2019. Workers at Film at Lincoln Center voted to unionize in November 2020 and are now in the midst of a contract dispute; workers at Anthology Film Archives won union recognition in July 2021 and conducted a one-day strike on March 31 in their own contract fight; and workers at Film Forum filed for a union election just last week. In trying to divine why a cinema might deny a forum for open discussion, we would do well to remember the first words of the Preamble to the IWW Constitution: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.”

Maxwell Paparella: What was your relationship to the labor movement when you began work on the film in the ’70s? You were both involved with the Newsreel Collective.

Stewart Bird: Yeah, we were both in Newsreel at the time. I had done anti-war films in Newsreel; Columbia Revolt [1968], a film about the Columbia [University] takeover. Then I was in Detroit doing Finally Got the News [1970], which is about Black autoworkers. Deborah came out with a friend who I knew from New York Newsreel. She was in Ann Arbor going to school and setting up a little Newsreel there she called a satellite. We distributed the Newsreel films. And then years later, we met back in New York. I had done a play about the Wobblies . . . at the Hudson Guild Theater in New York.

Deborah Shaffer: Stu was in Detroit, I was in Ann Arbor. Contemporary labor history was all around us. But neither of us had grown up knowing anything about the IWW. In fact, they were completely written out of history. And somebody had given me a book called Milltown, which was about the Lawrence[, Massachusetts textile] strike in 1912. It was a book that had been banned in the 1950s. It was just a picture book of the strike. And it made a big impression on me. . . . The fact that this book was banned I thought was horrifying. And the fact that I'd never heard of the IWW was even more horrifying. How had this whole vast part of labor history completely escaped my notice growing up? It was not in any history books in any school I ever went to, or [in] anything I ever read. So I was kind of primed for it.

And then Stew had this play on, so I went down to the play. And the night I was there a couple of older Wobblies who lived in the area had come out to see the performance. And they were all crowding around the stage afterwards. They were all so lively and excited about Stew’s play. It just struck me right then and there that we had to do a film with them. Because it was clear that they were very elderly. They weren't going to be around for long. And since this was a completely unknown history, if we wanted to get it we had to do it while they were alive. . . . We weren't sure in the beginning if we would find ten Wobblies or fifty. . . . In the end we located and filmed about twenty-six surviving Wobblies, and I think nineteen of them made it into the film.

MP: It's so powerful to hear these older people sitting around their kitchen table or on their front porch and saying things like, “You either have to just stop living or become a rebel.” Did you expect to find their convictions so entirely undiminished?

SB: They had still had the conviction. And amazingly, what they remembered was so accurate—in terms of time, days, dates. . . . They remembered it like it was yesterday. It was so important to their lives.

DS: The thing that did strike us was that they were all so extremely humble. We went to New Jersey, to Paterson—and this happened over and over again—we would get to somebody's place, and we would start to get set up, and they would say, “Are you sure you want to hear this? I mean, nobody's really interested in this.” And it turns out, nobody had ever asked them about their history. Sometimes their children didn't know, their grandchildren didn't know. So, some of them took a little bit of just warming up, but it didn't take much. Once we got going the floodgates were open. But that was a really universally striking phenomenon. They were humble people.

MP: The film premiered in 1979 at the New York Film Festival. What was the initial reception, by the public and by its subjects?

DS: Well, unfortunately, they didn't even all make it to the opening. When we opened in New York, we invited the people who were [in the area]. . . . I'd say the reception was excellent. You know, it wasn't like a popular popular movie, but we had wonderful reviews. . . .

SB: It stuck out.

DS: There weren't a lot of films like that. We were sort of at the beginning of a whole pioneering era of labor history films. You know, films like Union Maids [1976], Seeing Red [1983], [The Life and Times of] Rosie the Riveter [1980], The Good Fight [1984], With Babies and Banners [1979]. There were a number of history films that came out around the same time.

SB: Barbara Kopple.

DS: Harlan County [1976], of course. How could I not mention Harlan County? But if I told people that I did documentaries, they were like, “Oh, you poor thing.” . . . Because people thought of documentaries [as] something you were subjected to in school. I think we really helped pioneer a whole turnaround in what documentaries could be and this whole idea of historical documentaries that were both educational and informative, and entertaining and good movies. . . .

MP: I'm curious about your treatment of the archival material throughout the film. You use voice actors to deliver quotations from the unionists and from industrialists—I think I noticed Rip Torn’s name in the credits. You also use Foley to embellish the silent film material.

DS: We used parts of Stew’s play to open and close the film. We were doing a people’s history really out of necessity, partly because the leaders were all gone. But we couldn't just ignore them, so the only way to include them was with voiceover read by actors. And that had not really been done before. Now it seems very commonplace. This is ten years before Ken Burns did The Civil War film [1990].

SB: I think it was because all we have are the interviews, these incredible stories of people's lives. And we needed to develop a way to tell the whole story. . . . Rip Torn came to the play. I noticed him. He came with Geraldine Page. He lived not far from the Hudson Guild Theater. And I just called him afterward and asked him if he would do it. And he agreed. And some of the other actors were from the play itself. [For] a lot of the singing, we had to reach out to Seeger—

DS: Mike Seeger, the brother of Pete Seeger.

SB: For the Lawrence Strike, people knew some Italians who could sing. We tried to be accurate, in terms of everything we did. But I guess everything was out of necessity. We wanted the film to work. . . . We wanted to make it entertaining. The Wobblies had a sense of humor . . . and so we wanted to have some of that feeling.

MP: One of the big revelations of the film aside from the voices of the Wobblies themselves is the propaganda animation that we see throughout targeted against the union. Do you know where these animations would have been seen originally?

SB: That's a good question. [laughs] But I know who got them for us. We had a friend, Pierce Rafferty. I think he must have had a cot in the Library of Congress, because he was there 24/7. And he was working with his brother, Kevin, and Jayne Loader doing research for their film, [The] Atomic Cafe [1982], an incredible film. He said he would take on the job for us, he would find whatever he could. He found stuff that was mislabeled, misfiled. He really did an incredible job of finding those cartoons.

DS: One was called “Alice’s Egg Plant” [1925, part of Walt Disney’s “Alice” series – Ed.]. He found “the little red henski” one, the anticommunist one. One of the cartoons was made by the Ford Motor Company [in 1919]. Their credit is at the end—the one about the farmer with the shovel hitting the Bolshevik rat. It was just plain old corporate anti-communist propaganda.

MP: There's also plenty of the IWW's own propaganda in the film, illustrations in which the union is portrayed as a steamliner or a locomotive, or as the the sun itself rising over a grainfield. You're also using newspaper clippings to demonstrate the media's investment in capital. The death toll of a police attack on striking workers will be the third sub-headline under “Continued Delays in Production in Paterson,” or something. The documentary is a corrective to some of that media history. Do you think of your own film as a form of propaganda?

SB: No, because I think we were being very honest about who these people were. I mean, we didn't try to cover up. . . . We weren't trying to hide the reality of how they reacted to the kind of repression and violence against them. We tried to be real about it. But the repression against them was so unbelievable. You were taking your life in your hands, literally, organizing at that time.

I'm sure you know the story of Frank Little, which we didn't put in the film, but we might mention him. There's a book by a relative [of mine, Jane Little Botkin] Frank Little and the IWW [2017]. He was rounded up by Pinkertons and hung from a [railroad] trestle. It was such brutal stuff. Even Wobblies who had fought in the war and returned— There was a story up in the state of Washington about someone being hounded and murdered. So the repression was so incredible that you showing how the Wobblies reacted to it in a real way, getting violent themselves or breaking machinery or whatever, seemed very small in retrospect.

DS: I went into [making the film] thinking that the IWW had sort of petered out, that they had sort of destroyed themselves by internal dissension after the revolution in the Soviet Union. Some of them had gone over to the Communists, and some of them wanted to stay on the more anarchist side of things. Like other left-wing organizations of our era, they were sort of torn apart by internal dissension. What I learned making the film is that that was partially true, but much more true was that they were destroyed. They were destroyed by the powers of the government. They were destroyed by A. Mitchell Palmer and his young new assistant, J. Edgar Hoover, in much the same way that the films that are coming out now say about the Black Panther Party. You don't have a chance at a certain point when those kinds of governmental forces are unleashed against you, when they're willing to send you to jail, when they're willing to murder you, when they're willing to threaten your family, when they're willing to smear you, when they're willing to do anything to to discredit you and put you out of business. You don't have a chance, you don't have a fighting chance. The Wobblies, in the end, did not have a chance. They were destroyed by repression.

MP: What was it like to reapproach this film after more than thirty years away from it? Are you finding new resonances with our own moment of increased labor activity?

DS: I would love it if the film wasn't relevant today, I mean if it really was more of a finished history. We got where we are now in 2022 because of a screening we did in 2018. We hadn't seen the film in many years, and Stew and I were both there for a Q&A at an organization called UnionDocs in in Brooklyn. And I think, everybody in the audience, we were all stunned that night by how relevant the film was. . . .

SB: We're having the Amazon Labor Union at the screening on Friday, with Deborah and me. . . . As soon as I saw Chris Smalls on TV, that was it, man. He is so much connected to what we did in that film. And Deborah and I are so excited about all this union activity, it's great. Because people are going from the ground up, they're doing their own unions, or they're reviving things.

DS: Yeah, it’s the wave. It's coming. I think we're on the verge of a turnaround.

A new digital restoration of The Wobblies is screening nationwide for International Workers Day and is available on demand.