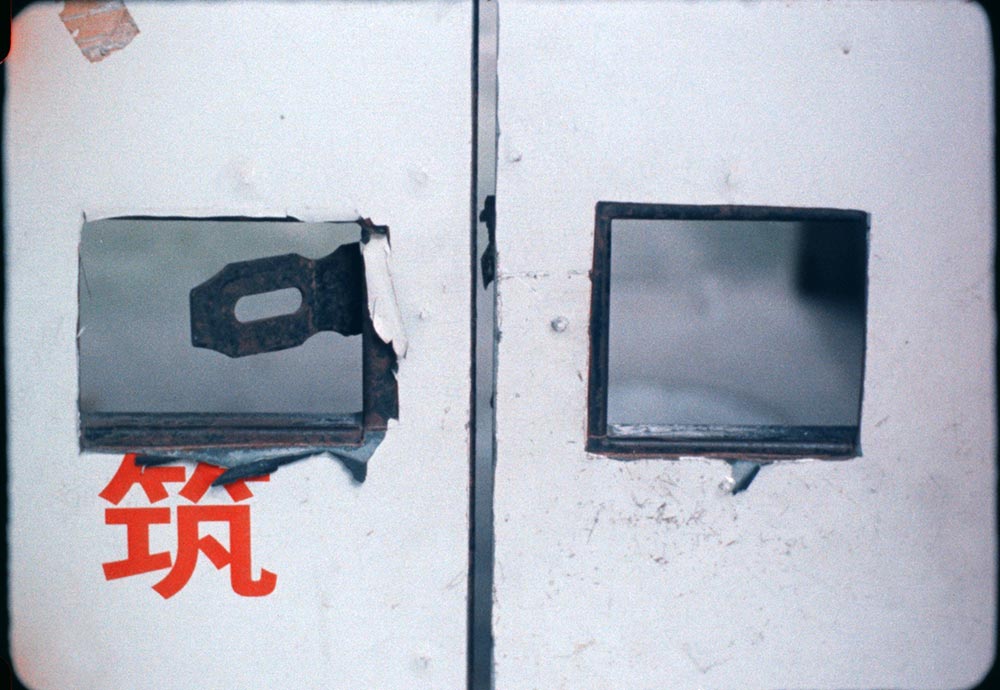

In Lily Jue Sheng's Heritage Architecture (2024, pictured at top), the camera documents buildings and zones of commerce in the port cities of Shanghai, Keelung, Taipei, and Taoyuan. The camera lingers unsteadily on signs and shop windows, in addition to panning across skylines and parks. While walking through the Hongkou neighborhood in Shanghai where their family grew up, Sheng captures a mixture of eminent domain and new developments in an area that used to be home to early Communists and progressive cultural leaders. Clips of Lu Xun Park are accompanied by the sounds of choir practice and public karaoke. The classic ‘90s song "Flowery Heart" transitions the film out of Shanghai and into Taiwan, where Sheng also films street performances, as well as night markets and temple architecture. All of Sheng’s footage is captured with a handheld Bolex camera, and the sound composition is a mixture of on-location cell phone recordings and scored sound.

Sheng cites Japanese landscape theory films such as Masao Adachi’s A.K.A Serial Killer (1975) as an influence on them. The experimental documentaries from this movement show that a range of power relations can be expressed simply through depictions of landscape itself; similarly, Heritage Architecture invites the viewer to investigate the social and economic infrastructure that layer its pedestrian scenes, and how, as the title prompts, these environments can transmit, alienate, and commodify a sense of heritage. The film begins with footage of lilong, a popular housing model that developed during Shanghai's Treaty Port Era and is now under the threat of disappearance. Lilong houses, which were less adaptable to changing generational needs than traditional courtyard compounds, introduced a concept of homeownership in Shanghai wherein houses were treated less like family heirlooms and more like commodities to be bought and sold.

Sheng's aunt lives in one of these lilong neighborhoods, but because she was busy caring for a sick relative, couldn't receive Sheng as a visitor. Sheng mentioned this to me during a phone interview, wanting to be explicit about why footage was shot from certain vantage points and also to highlight the material conditions involved in producing their film. "I typically do all my film work with no time, no money, no permits or permission, no extra help, and no significant insider access," Sheng explained. "I used film stocks that would work in available light and only shot handheld for Heritage Architecture, because the heat was intense and the time was too short to consider working with subjects."

During our conversation, Sheng also described their aim to draw attention to the worker status of artists and artist-filmmakers with their films. In their view, this is a status that is often obfuscated by art world pressures to "reproduce bourgeois aesthetics and modes of production which necessitate that you act like you don't need a job." This drove their decision to forego a festival run and premiere their film at Anthology Film Archives, their place of employment for a decade.

"We tend to relegate sharing cultural production to spaces of exceptionalism," Sheng said. "I'm trying to demystify a romanticism around what artistic practice is, spiritually and economically. I'm showing my work in a space that's institutional, but the institution also represents a kind of mundane day job."

Work and Place in the Workplace: The Films of Lily Jue Sheng takes place tonight at Anthology Film Archives. Lily Jue Sheng will be in attendance for a Q&A.