This week at Anthology Film Archives, four films with nearly identical titles explore sex, labor, and class in incisive yet accessible ways. Spanning nearly six decades of cinema and featuring the work of several pioneering female filmmakers, the series shows that, whether it's in a brothel or in a boardroom, being a working girl is not easy.

Dorothy Arzner’s surprisingly fresh pre-code drama Working Girls (1931) follows two Midwestern sisters, Mae and June, who move to New York City in search of opportunity (namely, the opportunity of securing men who can provide for them). They work and date and have fun in the big city, but when Mae becomes pregnant, the sisters collaborate on securing a husband for her, knowing that single motherhood will be damaging to her future prospects. Made by one of the only working female directors in the 1930s and ’40s (and perhaps the only queer one), and written by the Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright/screenwriter Zoe Akins, it’s a frank and feminist film, one that’s honest about the very unromantic role that marriage has played in women’s lives. Even as our protagonists do find romance, their desire for marriage is ultimately an economic one, and this knowledge determines how the sisters approach their dating lives.

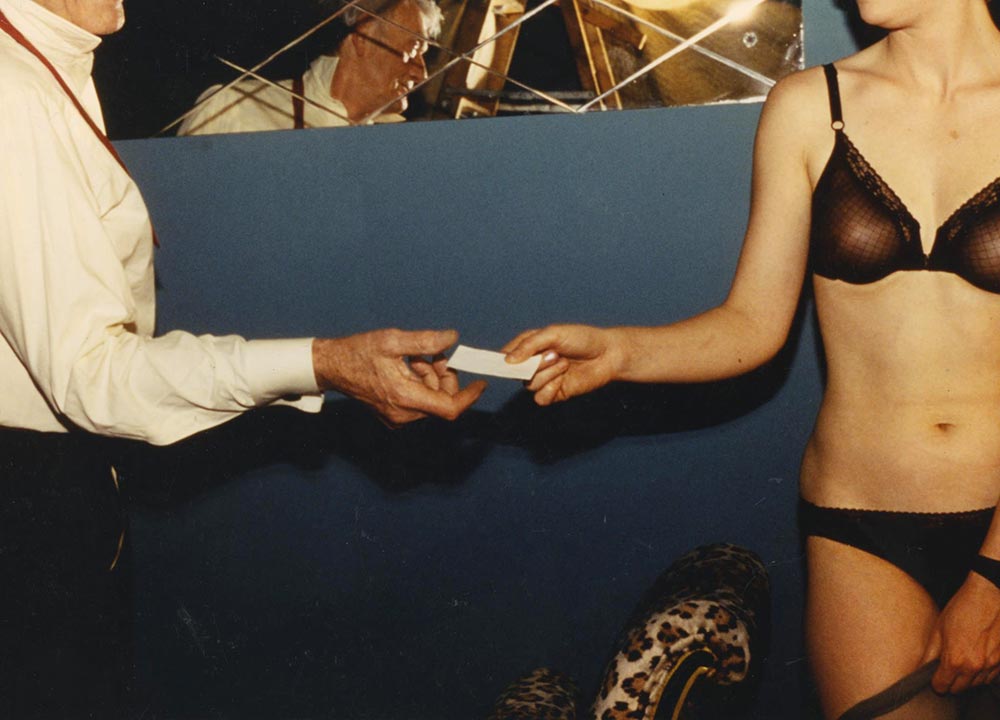

The last film by Stephanie Rothman (The Student Nurses, Terminal Island), The Working Girls (1974) is a sexploitation movie with more female camaraderie than carnality. Famous for a topless dance performance by Cassandra “Elvira” Peterson (in her first credited role), The Working Girls follows three friends/roommates (Sarah Kennedy, Laurie Rose, and Lynne Guthrie) as they move in and out of shady jobs, schemes, and relationships in down-and-out Los Angeles. It’s a fun low-budget romp that captures the web of personalities and scenarios one encounters when they’re forced to hustle to get by, and how women stick together in order to evade or combat the men attempting to take advantage of their low rung on the ladder. It’s a landscape Rothman knows well; she was already a trailblazer as one of the lone women making exploitation films in the 1960s and ’70s, but since she was never offered a path into the Hollywood system the way some of her male contemporaries in the school of Roger Corman were, she used the vehicle of exploitation film to sneak in feminist analysis and fully-written female characters.

The impetus behind this series, Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls (1986) depicts a single workday in a Manhattan brothel, in which sex workers navigate the daily stressors and boredom of their job, the physical and emotional expectations of their male clients, and their tempestuous madam. Molly (Louise Smith) is an aspiring photographer who is supporting her girlfriend and daughter, and we accompany her throughout her double shift. She and her coworkers juggle various jobs, not all of which are sexual: they answer the phone and keep the books, clean the brothel and restock supplies, and act as therapists for some of their clients. By desensationalizing sex work, Borden creates room for authenticity in her characters as they help one another, make each other laugh, gripe about the boss, etc. And by carefully eschewing the notion that sex work is inherently more or less exploitative than any other kind of job, Borden is able to put the political stake in the ground that all wage labor is exploitative. If it isn’t clear enough by the end of the film, Molly asking her boss if she’s ever heard of surplus value certainly drives the point home.

Rounding out the series is Mike Nichols’s hit rom-com Working Girl (1988), a film heralded at the time for its look at workplace gender dynamics, but which also has garnered a complicated legacy for its narrative reliance on pitting two female leads against one another. Tess (Melanie Griffith) is a working-class woman from Staten Island with ambitions of climbing the corporate ladder. She earns her business degree by taking night classes while working as an administrative assistant and is delighted to finally be employed by another woman, Katherine (Sigourney Weaver). But when Tess learns Katherine may be trying to steal her idea for a corporate merger, she takes advantage of her boss being incapacitated from a skiing accident to foil her plan, ruin her reputation, and even steal her boyfriend (Harrison Ford) in the process. Tess trades in her teased hair and cheap clothes for a more polished look, but she struggles to imitate the casual refinement of someone like Katherine, who was formed by the elite halls of Wharton. Cat-fighting aside, Working Girl is shrewd about the class difference between its female characters, who could hardly be allies.

“Working Girl(s)” runs February 25 through March 2 at Anthology Film Archives, with all screenings on 35mm. Lizzie Borden will introduce her Working Girls tomorrow, February 25, and will also present two films she guest-selected this weekend: Sheila McLaughlin’s She Must Be Seeing Things (1987) and Pat Murphy and John Davies’s Maeve (1981).