“The planet earth is dying. The disease is sin.” A somber voice intones these words over images of stars and biblical text. More voices are heard — phony Russian accents through military radio static — and, then, an explosion. It’s the end times, and, in Donald W. Thompson’s Prodigal Planet, that’s a very dangerous place to be.

Prodigal Planet is the final chapter of Thompson’s epic evangelical exploitation series, A Thief in the Night. The director’s previous three films slowly ratcheted up the grimness and grisly (mostly implied) violence, as those who refuse the mark of the beast are led to guillotines. Prodigal Planet takes what’s come before — scare films that imagine what life on earth would be like after the Rapture — and thrusts it into high stakes action movie mode. A car slams into a train and a Christian rebel guns down one of the Antichrist's henchmen as a minimalist Carpenter-like synth line throbs on the soundtrack. In this final post-apocalyptic chapter, the series reaches surprisingly Romero-esque heights of dystopian horror. It’s been a long, alarming, and stupid road to get here, but, obviously, that’s part of the fun.

The Thief movies concern the Rapture, a purported time in Christian theology when all believers — living and deceased — will ascend to heaven to kick it with Jesus before his eventual Second Coming. Between this mass earth exodus and Jesus’s return, however, comes the time of the Great Tribulation. During this in-between period, the Antichrist comes, people get branded with the mark of the beast (what the films depict as a satanic credit card), and a series of plagues wreak havoc on those who are “left behind.” Thompson’s films deal with the specifics of the Rapture and Tribulation in excruciating detail at points, functioning first and foremost as vehicles for Christian rhetoric.

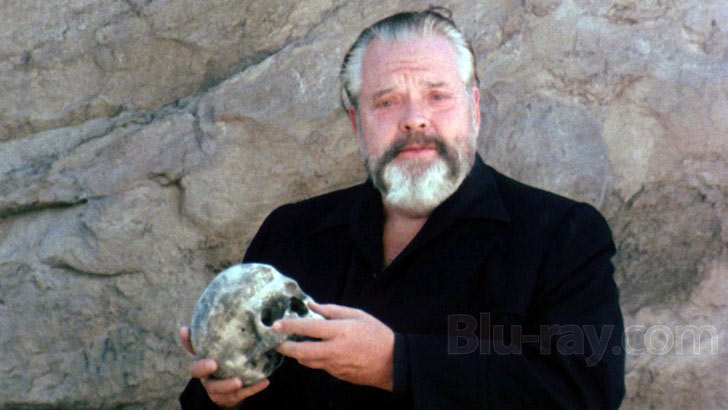

The Rapture set the public’s imagination on fire in the 1970s. The Thief in the Night films certainly had a hand in this eschatological trendsetting, but the end times-themed books of Hal Lindsey were more directly responsible. The Late, Great Planet Earth (1970), Lindsey’s most famous work, was crowned the bestselling nonfiction book of the decade by the New York Times. It spawned a primetime TV special and a 1979 film narrated by Orson Welles. In his work, Lindsey, a Christian Zionist, melded current events with Biblical prophecies to create a melodramatic Christian fantasy that would function as an antivenin for contemporary anxiety and political turmoil.

Lindsey believed the Rapture would come in the 1980s, making it the last decade of human history. In his book The 1980s: Countdown to Armageddon, which sat on the New York Times bestseller list for some 20 weeks, he outlined several scenarios that might spark this cataclysmic event and the tribulation period after it, like a global takeover by Communists or an unforeseen Soviet nuclear attack. The Rapture did not come in the 80s, but the 90s did bring Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins’s mega-successful Left Behind-series, which jumped from page to screen with the insufferable Christian D-lister, Kirk Cameron, as its star.

In 1972, Douglas W. Thompson, a radioman, and Russell S. Doughten Jr., a filmmaker who cut his teeth on the 1958 classic The Blob, formed Mark IV Pictures and produced A Thief in the Night, the first entry in what would become the homonymous quadrilogy. Thompson directed the film for $68,000, and it went on to gross over $4 million. The film begins, like the Left Behind series, in the middle of a mysterious global event where huge numbers of people have simply disappeared. A young woman, Patty Meyers, searches for her husband, Jeff, who, in the wake of a dramatic snake bite, has recently devoted himself to Jesus. Patty, a more casual Christian — a key distinction in the series and in evangelical eschatology — is forced to survive under an increasingly fascistic one-world-government, U.N.I.T.E., led by the messianic Brother Christopher (the Antichrist). Her harrowing experiences are revealed to be a dream, before a final twist confirms that they’re about to occur in reality. A Distant Thunder (1978), continues Patty’s story, with the protagonist imprisoned and awaiting execution by U.N.I.T.E.. One of her fellow prisoners implores her to share her experiences, and a flashback shows Patty desperately struggling to survive in the barren countryside without accepting the mark of the beast.

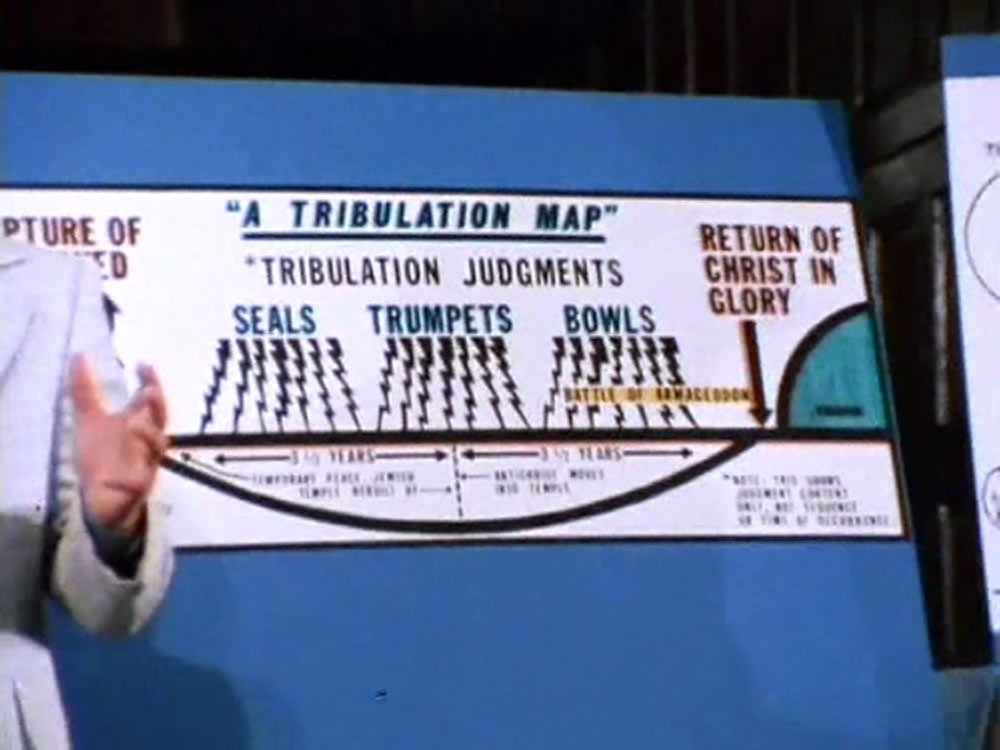

In a surprising pivot, Image of the Beast (1981) turns its attention to David Michaels (played with excessive gravitas by William Wellman Jr., son of the famed director), a devout Christian and gifted computer programmer. Michaels attempts to create a counterfeit mark in order to circumvent U.N.I.T.E.’s brutal regime. Approaching the film’s climax, the programmer, traveling with a woman named Kathy and her son, takes refuge in a Night of the Living Dead-esque farmhouse. There, Michaels encounters the Reverend Matthew Turner (Russell S. Doughten Jr.), who, using copious charts and graphs, explains the biblical horrors that the upcoming Tribulation will bring. Michael and Kathy eventually create the counterfeit mark with the help of a pamphlet Kathy purchased at a grocery store years earlier entitled “Computer Prophecies.”

Prodigal Planet begins exactly where Image leaves off, showing a captured Michaels facing the guillotine. He escapes after a nuclear explosion, and the film chronicles his travels through a post-apocalyptic wasteland filled with mutants and soldiers of the Antichrist. Michaels’ goal is to hack the mainframe of U.N.I.T.E.’s computer in order to stay out of the government’s hands as Jesus’s return draws near.

While the first two Thief films feel like a mixture of 70s exploitation and educational fare, Prodigal Planet, with its barren landscapes and episodic, survival horror structure, is closer to Dawn of the Dead and Night of the Comet. The series is rare in its tonal and material scope, moving from the quaint ineptitude of regional low-budget filmmaking to plausible, dystopian genre film in the vein of The Omega Man.

As silly as these films tend to be, there are moments that are surprisingly effective. Memorably, in A Thief in the Night, a Shaggs-esque band performs “I Wish We’d All Been Ready,” a song written by Christian rock megastar Larry Norman. Lamenting the tragedy of being caught unprepared when the Rapture comes, they sing: “There's no time to change your mind / How could you have been so blind / The father spoke, the demons dined / The son has come and you've been left behind.” Though laughable, the sincerity of the lyrics and the earnestness of the performance create a chilling effect.