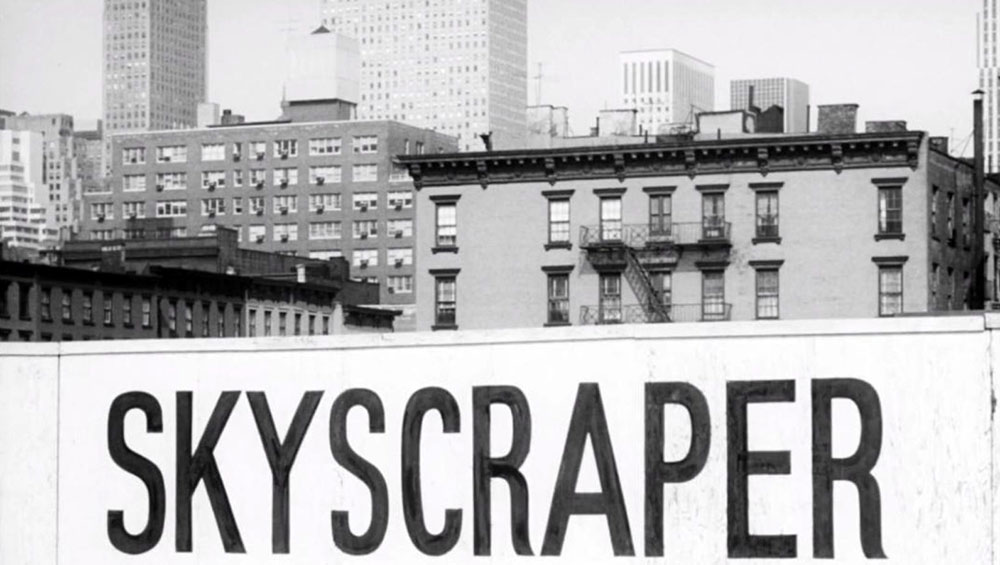

Shirley Clarke’s Skyscraper (1959) is just as much a dance film as her earlier, more traditional forays into the genre, except this time buildings are cast as the principal performers. Skyscraper heads “Program 4: Architecture and Gendered Space” of Film at Lincoln Center and The Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s “Seeing the City” series, where audiences will find that Clarke’s balletic direction and editing, which capture the musicality of city construction, are not the film’s only innovations. Tishman Realty & Construction Co., along with steel, metal, elevator, and air conditioning companies, sponsored Skyscraper in order to document the erection of Manhattan’s 666 Fifth Avenue, also known as the Tishman Building. Defying the expectations of a corporate-backed documentary, Clarke uses a suite of silly songs and jocular voice-over from fictional construction workers to turn the film into a “musical comedy,” as she termed it. A children’s educational film might be another apt description, as the viewer learns how to “put a ‘scraper in the sky” step-by-step while enjoying snappy tunes and wise-guy gags.

Like Skyscraper, the Tishman Building itself had both high art and comedic flourishes. An Isamu Noguchi sculpture graced its lobby, but was dismantled during a remodel in 2020. Its devilish street address was once worth a chuckle, but apparently the joke got old; it was renamed 660 Fifth Avenue in 2021. 65 years on from Skyscraper’s release, as corporate profit-seekers swallow up more and more of the city, Clarke’s facetious optimism for New York’s future also feels like a thing of the past.

Building a skyscraper is a rather macho endeavor, but women workers do appear in Skyscraper—for about four seconds. “A lot of dames helped on this one,” our narrator assures us. We’ll just have to take his word for it, as Clarke emphasizes how masculine the entire operation is, from the executive personnel, to the culture of the construction site, to the phallic nature of the end product. The idea of separate realms for men and women—public versus private—lingered far beyond its Victorian origins, and the only place where women explicitly belonged in a skyscraper may have been their gender-designated restroom.

The ladies’ room is the setting for the two other films in “Architecture and Gendered Space”: Holly Fisher’s From the Ladies (1978) and Bette Gordon’s Greed: Pay to Play (1987). In From the Ladies, a wall of mirrors, floral wallpaper, and checkered tiling in a Holiday Inn bathroom swirl together in an act of cinematic hypnosis. In Greed, a hotel restroom attendant takes revenge on a wealthy guest who destroys her lottery ticket. Using drastically different approaches, both films envision the women’s bathroom as a place of secrets. Fisher includes voice-over from hotel staff whose gossip, venting, and confidences turn the space into a confessional. For Gordon, the restroom is where you can get away with murder.

The two films feature an element of bathroom design that has become archaic: a powder room for lounging, primping, and makeup application that adjoins a separate space for toilets and sinks. These parlors were intended to make middle and upper class women feel at home, and Gordon’s film in particular identifies the class dimension of this design. Today’s bathrooms are neither glamorous, nor accessible: in a city where 1,100 public toilets serve a population of 8.3 million, New Yorkers struggle to find a free place to piss. They could try their luck masquerading as a guest at Fisher’s Holiday Inn, the first in Manhattan, which left the chain in 2017 and rebranded itself as The Watson Hotel. Gordon’s filming location, however, is no longer an option: the Palladium, one of Manhattan’s most extravagant nightclubs, is now a New York University dorm. Of all the media coverage of the Palladium’s 1985 redesign, none of the articles describe the women’s restroom; its rendering in Greed—very posh, very pink—is one more powder room secret.

Architecture and Gendered Space screens this evening, May 6, at Film at Lincoln Center.