Under the opening credits our fresh-faced hero arrives, puffed up in a leather jacket and piloting his moped along the open road of destiny—only to be overtaken by an unhurried cyclist. He endures with relative aplomb. He is easy to root for. Soon he’ll discover the sublime, unguarded intimacy of first love—and that it’s a fleeting interlude in the cruel world of disappointed adults. With its honeyed summer light, traipsing camera moves, and close focus on rapturous glances, A Swedish Love Story (1970) remains as sincere and tender a depiction of adolescent romance as movies ever will provide. It’s also somehow a Roy Andersson film. You can tell by the attention to indignity.

In his debut feature Andersson wasn’t yet the surrealist virtuoso and purveyor of coolly configured, artfully drab dioramas, playing self-delusion and indifference for the driest possible laughs. But clearly his empathy for the bewildered was established very early on. It’s satisfying to look back, by way of “Being Human: The Films of Roy Andersson,” a retrospective at Museum of the Moving Image, and see his gallant, despairing worldview as something both innate and gradually evolved.

The enigmatic sophomore effort, Giliap (1975), is ostensibly the drama of a port-city hotel waiter who finds himself involved in a complex crime scheme. Prone to a loitering pace, casual disavowals of customary neo-noir self-seriousness, and poking around among genre possibilities, it seems in retrospect rather ahead of its time. It is now best understood as a passing tone toward the register of Andersson’s more familiar mature style, though its discordance with the popular cinema upon release famously yielded such a flop that he was deterred from making features at all for 25 years.

During that time he kept busy with commercials, which proved formative. The program also includes a selection of these, timeless little marvels of narrative economy whose swift comedic jabs can hold their own even against today’s most zoned-out social-media scroll. Here we find Andersson the more-with-less artist building out his world, with all its capricious and hilarious disappointments, in as few as 15 seconds at a time. “Sooner or later you need insurance,” one frequent tagline advises, and the thought of Roy Andersson as this doctrine’s one-panel concept man is somehow perfect: We never really know when or how things will go suddenly and spectacularly wrong; we just know that they will.

The ad work bought him time and space (in the form of his modest Stockholm studio) to grow weary of realism; to channel renewed inspiration from films by Buñuel, Fellini, Tati, and others, as well as from the most durable traditions of painting. What emerged was a new view of slapstick—the art of absurd collisions—as a life-affirming response to both the heaviness of history and the benumbing lightness of entropic capitalism. With the deadpan middle-class-malaise vignettes of Songs from the Second Floor (2000), Andersson was fully rebranded for the apocalypse-adjacent new millennium.

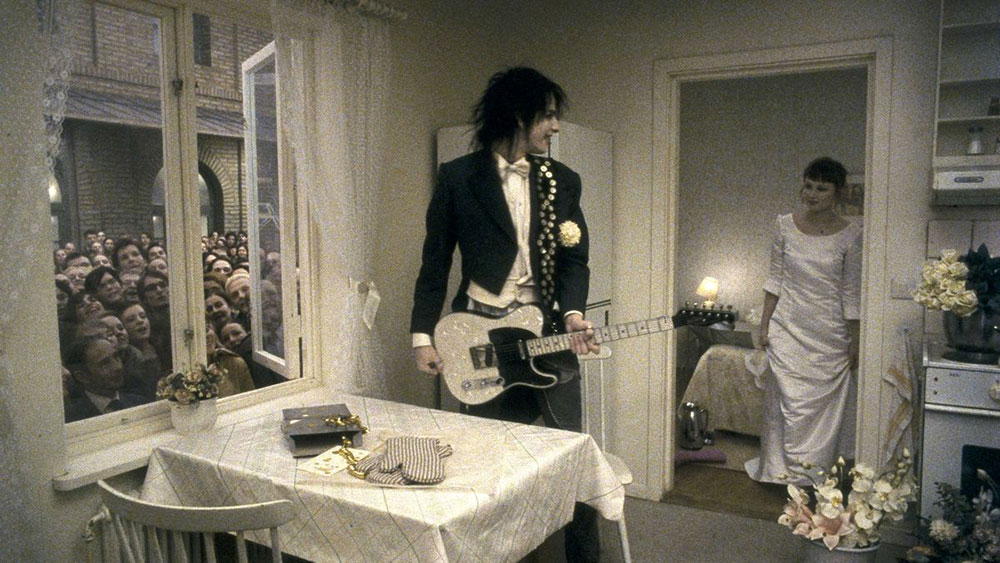

So began his “Living Trilogy,” which continued, after an anguished gestation and labor of several years, in You, the Living (2007), followed by A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (2014). These are films for the ages, codifying Andersson’s formal techniques—the resolutely stationary camera, the sharp diagonals hurtling into a haze of distance and time, the dismal monochrome and shadowless pallor, the frames which tend to feel empty except when thronged with a plenitude of gray-faced schlubs—and adding up, very movingly, to what feels like humanism’s last stand.

That the vignettes become somewhat interchangeable is part of their charm. Five years after concluding the trilogy he more or less resumed it with About Endlessness (2019), the one with the Chagall-ish embracing couple floating over a devastated city. (The last time Andersson took to the skies, an ominous armada of B-52s brought an end to You, the Living.) He’s been working at a mosaic of fine-cut fragments, this modular megawork of purified hilarity and despair.

“Many may ask, ‘What is art? What is it good for?’” the director says in the 2011 documentary profile Tomorrow’s Another Day, also screening in MoMI’s comprehensive Andersson-a-thon. “Its most important function is that it clarifies things. It casts light on things that you might not otherwise discover, thereby giving us a new perspective on our existence.” The documentary demonstrates this lofty philosophy as a humble modus operandi, showing Andersson and his team at work: blocking performers’ bits of business, figuring out their wonderful trompe l’oeil tricks of perspective, staging, shooting, quarreling, enduring. This was already three films ago now, so the endurance especially resonates.

About Endlessness is now streaming on Hulu, where it looks just fine if you don’t mind your scenes of downtown crucifixions and desperate firing-squad plea deals suddenly interrupted by enticements to Dunkin Donuts coffee, or, of course, whichever ad experience you prefer. (It’s too bad the maestro’s own commercials aren’t an option here.) Better to see it and his previous films in the cinema, bearing common witness with other hapless souls to Andersson’s pallid commuters clumped at the too-small bus stop during a downpour, or his defeated soldiers in the tundra on their infinite forced march, or the naked masses packed into a genocidal gas van, or the slaves forced by colonizers into a huge cauldron to be cooked alive. Yes, the attention to indignity can become overwhelming, but in Andersson’s steady hands it is also genuinely cathartic, and better, always, than ignorance of the same.

“Being Human: The Films of Roy Andersson” runs December 15–31 at Museum of the Moving Image.