First, a series of rainbow colored mushroom clouds; then: "World War IV lasted 5 days. Politicians had finally solved the problem of urban blight. 2024 A.D." So opens A Boy and His Dog, starring a young Don Johnson as Albert (a.k.a. Vic), an eighteen-year-old road warrior of sorts in a vast desert with nothing on the horizon but a few apocalyptic outposts and so-called "rovers," gangs of hungry men with seemingly endless supplies of ammunition. The first voice heard over the soundtrack is that of Blood—or rather, of Blood's thoughts. Blood is Vic's dog who communicates with his boy telepathically, and though he is no longer capable of hunting for food, he can smell a female with infallible accuracy. Vic and Blood spend their days plundering canned goods, searching the bombed out holes peppering the surrounding sand for breathing women, and occasionally stopping at a sort of marketplace mirroring the saloons of old westerns, where a tins of sardines and peaches can be traded for anything from a shower, a prostitute, or a seat at the little cineplex specializing in old stag films, to even a serving of freshly made popcorn.

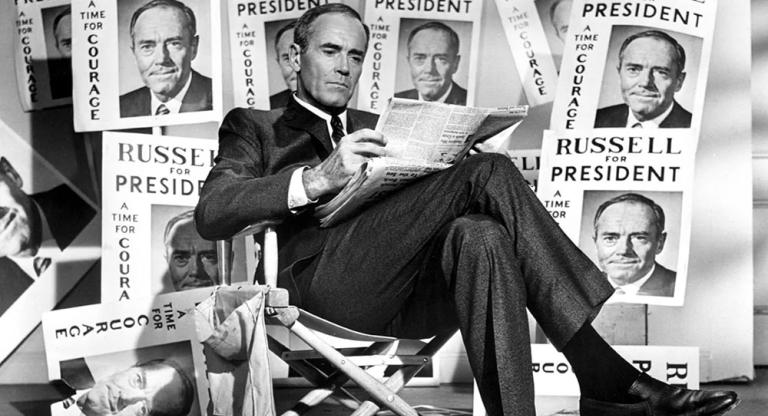

The second of only two feature films directed by L.Q. Jones, a Western stock actor best known as a Peckinpah regular, A Boy and His Dog (based on a cycle of stories by Harlan Ellison) offers a fairly typical vision of a lawless post-apocalyptic world overrun by horny men—until the final forty minutes or so, that isThe film veers from the standard vision of a bombed-out, resource-strained future when Vic enters the "down under," a temperature-controlled haven referred to by its denizens as Topeka. Run by legend Jason Robards, Topeka is a twisted recreation of small-town America, where the women all don long-sleeved, high-necked gingham dresses and the men are costumed as archetypes of an earlier era, and everyone wears a circle of blush on each especially white cheek, attempting to signal life amidst the uncanny day-for-night lighting of their little underground world. The horrific silence of such a place is beat back by the constant parading of a marching band and loudspeakers that, between official announcements, provide a running, even-toned narration of simple, homey recipes. Topeka represents a bizarre bastion of conservative ideology taken to its extreme and maintained via fear, violence, and fresh food, a darkly comedic vision of the "civilized" side of the post-nuclear future.

A Boy and His Dog's wry, dismal take on a world where sexuality and violence are the major projects of a corrupt leadership fits neatly with the sci-fi classics of 1975 (Rollerball, The Stepford Wives, Shivers). Envisioning an America where the list of recent presidents runs "Nixon, Ford, Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy..." and the latest world war begins and ends in just enough time for the "missiles to leave both sides," the film presents a unique, surreal, early-Cold War take on the apocalypse—a genre of understandable interest today.