"Beauty was not simply something to behold; it was something one could do,” wrote Toni Morrison in The Bluest Eye. Liza Mandelup's documentary Caterpillar (2023) is an uneasy look into the human desire to control one's destiny through one's appearance. The film follows David, a man on the cusp of 50, who, disillusioned with his life and desperate for change, flies to New Delhi to undergo an experimental cosmetic surgery—one that will change his brown eyes to a lighter, more “desirable” color.

Mandelup’s previous documentary, Jawline (2019), explored a similar yearning for escape through appearance, with a young social media influencer hoping to break free of poverty by capitalizing on his good looks. Here, the stakes are even higher. David isn't merely seeking fame, he's hoping to alter his soul from the inside out. As David undergoes his journey, we meet a cast of fellow patients: a male underwear model, a mother with swollen lips, and a chic Japanese man who doesn’t know enough English to understand the medical disclaimers he’s been given. Each, with their own wounds, express their hope that new eyes might offer a new life.

Those who are squeamish, beware. The surgeries, shown close up and unfiltered, are brutal to watch. With patients awake, needles are shoved into the eye and the inserted implants unfurl like dried petals in hot water. Multiple surgeries are botched. The mother’s implant was somehow cut during the procedure, leaving some of her dark pupil still visible. Two patients’ implants were switched, somehow. David asked for gray eyes, but the doctors gave him the nude models’ jade green. The implant surgery is performed by practitioners with no affiliation to the implant company Bright Ocular. The surgeons blame the company. The company is unreachable. David is furious, but eventually gives in, accepting once again a body that he didn't want. Was it fate, was it God, or was it the system? It doesn’t matter. It wasn’t his choice.

“We’re all exotic looking,” David says. He means that none of them are caucasian. Through heartbreaking interviews, we hear how these hopefuls were abused by their families and communities, taunted for being dark-skinned, unconventional, or gay. While Mandelup is clearly trying to make the connection between trauma and the desire for transfiguration, she also allows for some more positive stories of self-transformation. David’s best friend, a woman with breasts up to her chin and cheekbones pointing to heaven, had a supportive, loving relationship with her family. She just wanted to look different, and is glad that she now does.

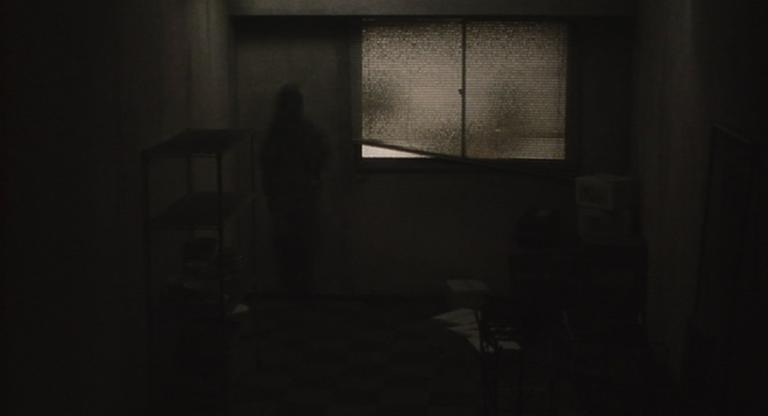

Body modifications are nothing new, but as technology evolves so do the possibilities. Mandelup’s philosophical inquiries into class, gender, race, and bodies are fresh and welcome. Unfortunately, they aren’t that interesting cinematically, at least stylistically. There are several slow-motion wrap-around shots of her subjects that feel like they came out of a Sears Portrait Studio. The title itself, Caterpillar, is heavy handed enough, but then we’re shown David wandering through a butterfly conservatory. Occasionally, we’re given a stunning non sequitur, like a heron gracefully drinking from a puddle of water in a gas station parking lot at night. But ultimately, and ironically, we need to overlook the aesthetics of a film to get to its postulations about appearance.