In the ‘80s, the Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay made waves embracing chance operations, sometimes cutting up vinyl records and performing the reassembled shards as mutant, noisy surfaces. The following decade, Marclay expanded his remixing practice from fractured sounds to sampled images, reconfiguring album covers with the Body Mix series (1991-1992) and post-producing found footage in his ongoing moving image practice.

Telephones (1995) is a 7-minute montage of scenes with telephones, from entering a phone booth to a flurry of characters dialing numbers, waiting, saying hello, and so on. Excised from narrative contexts and blended into a lyrical arc, the repetition of communicative gestures accentuates the acting, sound design, and cinematography within the excerpt and also points to all that is unseen and unheard beyond the splices. Marclay scaled this technique to extraordinary proportions with The Clock (2010), a 24-hour supercut compiled from thousands of films that matches diegetic time with the local time wherever the work is exhibited. The Museum of Modern Art will soon be presenting The Clock again, including some all-night screenings.

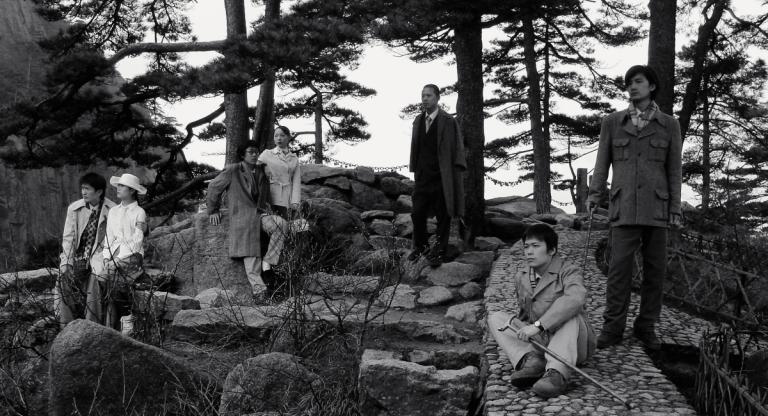

The art dealer Paula Cooper came across Marclay’s work in the late ‘90s and began representing him in her venerated stable of minimal and conceptually-oriented artists. In Marclay’s current exhibition at Cooper’s gallery in Chelsea, a hallway and small room of gleaming comic book collages are installed before the towering video Subtitled (2019), which emits from a nearly 20-foot tall LED slab. The work is a vertical stack of 22 rectangular strips, each one a shimmering cinema mixtape. Subtitled thus continues Marclay’s choreographic play with isolated fragments of films, but finds its origins in text rather than image or sound. Each of the 22 luminous rectangles are cropped from the bottom of film frames, where subtitles and captions often live. In addition to being a symphony of bright colors and camera movements, the mute work also speaks, with carefully metered and often overlapping subtitles presenting a hypnotic soliloquy.

At the opening in September, artists and curators gathered to read and listen to the LED monolith, including Joan Jonas, Stuart Comer, Shelley Hirsch, and Yoshiko Chuma. I sat on a bench in the elegant barn-like space and jotted down notes about the patterns coalescing into collective figuration and then dissipating. Amorous subtitles swell against yellow backgrounds and angry words shout in front of red. In one moment, many of the frames depict automobiles before giving way to a stretch of mismatched highway footage and a subtitle that reads “madness.” Next, “It’s stranger than fiction” briefly appears before all 22 segments flash in conflagration.

The art historian Hal Foster walked into the space just as I read the subtitle “Where is my mind?”—does Foster’s quip about Charles Ray’s dense sculptures being like catnip for art historians apply to Marclay for film and media scholars? Yes and no. Like Ray, Marclay is beloved for technical prowess and a mesmeric sense of space and time, but rather than working with allusive specificity, Subtitled anonymizes its source materials and achieves a sense of creative abundance from formal limitations.

Few faces appear because conventional cinematic perspective locates iconic forms at the center of the frame, and for Subtitled, Marclay looked to the linguistic margins of the film image. You cannot read all of the subtitles at once, so the work gives viewers a chance to walk away and return to find something new, with Marclay comparing the experience to revisiting a poem—legibility increasing over time.

Throughout the opening night, I cycled out from the Subtitled gallery to spend time with the collages in the front. The painter Trevor Warren told me that these framed works help demonstrate how Marclay clips. They are exquisite, especially a large composition that is mostly black ink, save for speech bubbles calling out in the darkness.

On the Saturday after Subtitled opened, Marclay and the polymath Wayne Koestenbaum were in conversation to celebrate the publication of the artist book Telephones, an adaptation and transcript of Marclay’s early work. In the glow of Subtitled, Koestenbaum riffed on dismemberment, glyphs, sutures, and following the French artist Stéphane Mallarmé in making disassembled, palimpsestic poetry. Marclay offered that he grew up speaking English and French, and was initially attracted to visual art and music because one doesn’t need to use words. In the early ‘00s, he collaborated on music with Michael Snow and then began working with onomatopoeia, which led him into text.

Marclay’s meticulous structural scavenging reconfigures cinema into a different kind of unity. Edited to his internal rhythm, his cinema collages continue to infiltrate the viewer in conscious and unconscious ways.

Christian Marclay: Subtitled is on view through October 19 at Paula Cooper Gallery.

Photo: Steven Probert, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.