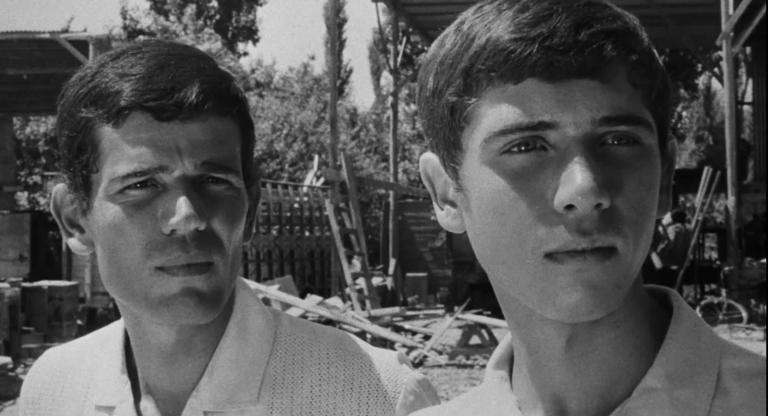

The first feature-length Palestinian fiction film was completed in Lebanon in 1982. Return to Haifa adapts Ghassan Kanafani’s novella of the same name, the story of a couple who lose their child as they flee Haifa in 1948. Twenty years later they return, only to find their house occupied and their missing son an IDF soldier.

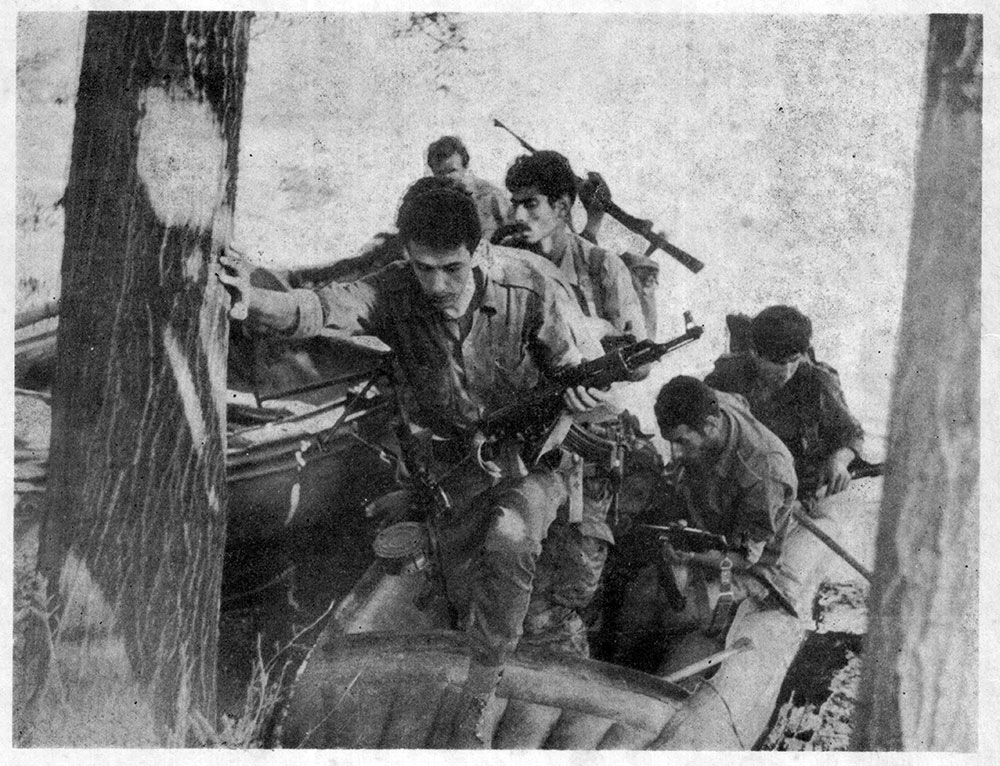

Director Kassem Hawal made Return to Haifa as a political exile from Iraq and a longstanding member of the Palestine Film Unit (PFU), the filmmaking wing of the militant Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Amid Lebanon's devastating civil war, the PFU gathered residents of the Niar al-Barid and Badawi refugee camps to re-enact their violent displacement from Palestine. Tripoli stands in for Haifa. Following the film’s release, the PLO left Lebanon and the invading Israeli army looted the PFU's facilities and massacred civilians in the Sabra and Shatila camps. In Hawal’s next film, the celebrated Palestinian Identity (1983), he returned to documentary, recording the ruins of education and cultural centers and conversations with Mahmoud Darwish; in the face of death and destruction, perhaps narrative fiction no longer seemed viable.

What is the role of fiction in militant and revolutionary filmmaking? In New York, we enjoy unprecedented access to Palestinian films, from open-access archives like The Palestine Film Index and Solidarity Cinema, and programs at cinemas throughout the city. Most of these films are documentaries, from PFU films to contemporary work by artists such as Jumana Manna and Mohanad Yaqubi. I am not surprised by this. Generally speaking, non-fiction films are easier to make with limited resources, and address the urgent need to witness, preserve, and educate.

Anthology Film Archives’ program Cinema of Palestinian Return stands out for its focus on the subversive potential of narrative and formal experimentation. May 2024 marks the 76th year of the nakba, and the ten selected films imagine and demand the return of Palestinians to their land. The program is guest programmed by Kaleem Hawa and Nadine Fattaleh, two young members of the diaspora. Each screening shows a “specific geography of Palestinian life” after 1948: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Occupied Palestine. These screenings will feature conversations between Hawa, Fattaleh, and other scholars and writers. Some are organizers active in the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) and Writers Against the War on Gaza (WAWOG), and have been supporting the students and faculty at Gaza solidarity encampments on local campuses.

For Hawa and Fattaleh, their program “traces the project of a collective cinema.” As a PFU production involving collective re-enactment, collectivity defines the making of Return to Haifa. The same can be said of amateur filmmaker Vladimir Tamari’s Al-quds (1968), in which re-edited UNWRA footage with his friends’ voices and music. Similarly, PFU member Mustafa Abu Ali’s Scenes from the Occupation in Gaza (1973) re-works footage shot by a French news team, allowing him to show Gaza despite physical exile. Many of the other filmmakers are not Palestinian; as today’s student encampments show, the collective project of freedom and return requires transcending borders and national identity. In the recent words of Nan Goldin, “the more of us there are, the more of us there are.”

The program opens with Lebanese director Christian Ghazi’s radical A Hundred Faces for a Single Day (1972, pictured at top). Described by Ghazi as his “manifesto on cinema,” this self-reflexive essay film merges documentary footage with narrative episodes and jarring, disjointed sound design and montage. In collaboration with his wife, actress Madonna Ghazi, Ghazi skewers the Lebanese bourgeoisie, whose misogyny and hypocrisy is contrasted with the militancy of the working class.

The films in this program show that fiction can be a means of entry or return, but also of exit. As the late Palestinian activist Basel al-Araj wrote in “Exiting Law and Entering Revolution” (translated this week by writer and filmmaker Bassem Saad), “the beginning of every revolution is an exit from the social order that power has enshrined in the name of law, stability, [and] public interest.” For many of these filmmakers, leaving the social order also requires exiting from the conventions of political cinema, especially indexicality, coherence, and didacticism.

Qais al-Zubaidi’s dream-like short The Visit (1972) abandons linearity altogether, and fragmented and elliptical narratives structure both A Hundred Faces for a Single Day and Kafr Qasim (1975), the great Lebanese director Borhane Alaouie’s first feature film. Filmed in Syria, Kafr Qasim reconstructs the 1956 massacre in the eponymous Palestinian town by the Israel Border Police. As Hawa writes of Kafr Qasim, “the film’s narrative threads remain unresolved, a tale of forty-nine lives cut short by a tightening project of settlement.”

A dialectic of absence and presence, and of entering and exiting, structures Kamal Aljafari’s found-footage film Recollection (2015). While watching a Zionist Chuck Norris thriller set in Beirut—The Delta Force (1986), filmed in Jaffa—Aljafari recognized a man from his childhood. After collecting images of Jaffa from dozens of fiction films made from the 1960s through the 1980s, he used editing software to erase each film’s focal points—its main characters—leaving backgrounds and extras only. In this act of detournement, he compiled an archive from these accidental records of the home to which he cannot return. Aljafari describes his process of subtraction as “cinematic justice.”

Locations in Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt substitute erased and recollected villages in Palestine. In Mohammad Malas’s stunning autobiographical feature The Night (1992), he was able to return to his hometown of Quneitra in the Golan Heights. Forced to leave by the Israeli occupation in 1967, Malas studied film in the Soviet Union. In The Night, Malas returns to the ruined and depopulated city and restages 1930s village life during revolts against the British and Zionists. The grave of Malas’s martyred resistance fighter father is still in Quneitra, and he represents this return through the perspective of a child. Voiceovers merge his refracted recollections with those of his mother, and Malas’s compositions—full of shadows, glass, and wind—are intensely beautiful. It was the first Syrian feature to play at the New York Film Festival. (In December, Anthology screened Malas’s stunning 1981 documentary short The Dream, in which refugees in Sabra and Shatila shared their nightly dreams, both humorous and tragic).

Hawa and Fattaleh cite Godard’s famous claim in Vivre sa vie (1962) that, following the Nakba, “the Jews became the stuff of fiction, the Palestinians, of documentary.” In support of Zionist fiction, Hollywood produced Otto Preminger’s epic Exodus (1960, with Paul Newman) and Melville Shavelson’s thriller Cast a Giant Shadow (1966, with Kirk Douglas and John Wayne). Yousry Nasrallah’s 2004 French-Egyptian production The Gate of the Sun is an anti-Zionist epic that plays like a response to Exodus. Based on Elias Khoury’s novel of the same name, the often lyrical film stars Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass as a militant revolutionary. As in Return to Haifa, history is viewed through the emotional story of a fictional family; in this case, the generational dissonance between a displaced father and a son born in exile. At nearly 5 hours, it is the longest film in the program.

This will likely be the first US screening of Khaled Hamada’s freshly subtitled The Knife (1972). The film adapts another family drama, Kanafani’s All That’s Left To You (1968), a tense novella that takes place over 24 hours in Gaza. The year of the film’s release, Mossad murdered Kanafani and his teenage niece in Beirut. Some Screen Slate readers will recall that last fall, the New York Film Festival premiered a restoration of another Kanafani adaptation: Syrian director Tewfik Saleh’s masterpiece The Dupes (1973), based on the novel Men in the Sun. Its screenings coincided with the start of Israel’s siege on Gaza.

Hawa and Fattaleh write, “the structures of this return are in fact highly practical: systems of organization, refusal, and care; networks of ideology and commitment; and a determination to think beyond the confines of current political possibility.” They hope to bring some of these films and discussions to the student encampments, where groups such as cinemóvil have already organized screenings. What is clear to the students, if not to administrators and hand-wringing commentators, is that ending genocide and the occupation of Palestine requires collective action. The program roughly spans two major days of strikes and direct actions: May Day and Nakba Day. In observation of calls for on-the-ground participation, there will be no screenings on May 15.

Cinema of Palestinian Return runs from May 3 - 18 at Anthology Film Archives.