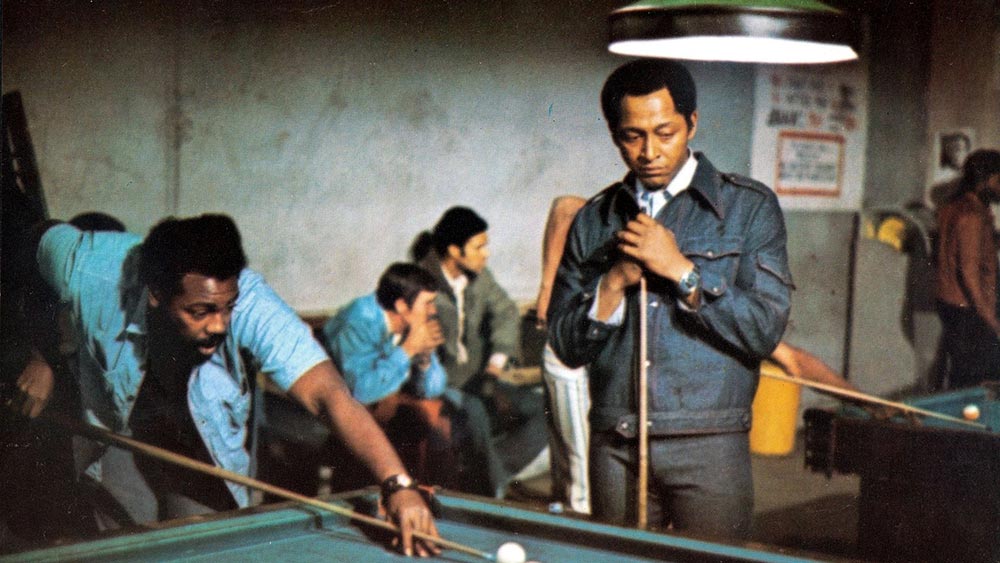

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973) is a rare portrait of Black counter-conspiracy, a living nightmare met with direct action. After becoming the first Black CIA Agent, Dan Freeman (Lawrence Cook) returns to his old Chicago neighborhood to train a Black liberation guerrilla army. The army makes use of Black stereotypes of incompetence and drug use to organize right under the enemy’s noses, outsmarting the CIA officials tailing them. Released in 1973, this film falls squarely between the era of Blaxploitation cinema and that of political conspiracy thrillers like The Parallax View (1974) and Three Days of the Condor (1975), synthesizing these genres in unique and thrilling ways. Unlike many of the sensational Blaxploitation films from its time, Spook relies on a reserved visual style to portray a clear view of Black revolutionary militancy. And unlike the average conspiracy thriller, the audience is let in on the scheme.

This is a film in which the ends are clear evidence of the means. Director Ivan Dixon and writer Sam Greenlee had to “steal” footage on the streets of Chicago because the local government refused to grant them shooting permits. When showing the film to studio executives, they highlighted its action sequences during preliminary cuts in order to obtain finishing funds from United Artists. Like Freeman, they flew under the radar by superficially meeting others' expectations to push their project through—even if it was banned by the FBI shortly after release. I spoke with their daughters, Natiki Pressley and Nomathandé Dixon, who worked with the Library of Congress stunning 4K restoration of this Black independent classic.

Zenzelé Soa-Clarke: I wanted to start by asking both of you what your earliest memory of The Spook Who Sat by the Door, the film and the book, was.

Nomathandé Dixon: The film was made when I was eight years old, just to give you some perspective. But I definitely have memories. Actually, this weekend I was asking my brother if he remembered the wrap party at the house.

I just remember certain details. I remember them going on location in Chicago. One of my oldest brothers was able to go out there with them. I remember all the artwork in the house being taken off the walls and used for the production. It’s those types of memories that you have when you're younger, and then it's just been a part of our lives over the years because there's been different efforts around the film, it always kind of comes around. But my earliest memories are just the excitement around the production and making it happen. And that wrap party. [Laughs]

Natiki Pressley: Well, for me it would be different because I was probably about three when this was made. I was in New York at the time so I wasn't around during the film production, but my earliest introduction to the film was probably when I was about ten or eleven years old. I had seen the book in my house forever, but I never really made the connection between the book and my father because my father was living in Chicago. I was living with my mom in New York, and so when I saw my dad most of the time it was just dad, it wasn't Sam Greenlee, the author.

Our time together was really precious because I didn't see him every day, so the time that we spent together was mostly talking about daughter-father things. But I finally experienced [Spook] when someone else told me about him and said, “Did you see this film of the book that your father wrote?” And I was like, “My father wrote a book?” That was probably when it all came together for me.

ZSC: That makes sense. And then fast-forwarding to this project, I'm curious what inspired you both to revisit the film and undertake this restoration now. Was there anything that surprised you about the process?

ND: There was actually a digital re-mastering in 2003, but over the years the film has had its underground playing and duplication efforts. Many collectors had prints and certain venues would ask for permission to show them, but the quality was degrading. The digital remaster was done for a DVD production through Tim and Daphne Reid's company, but around some years ago there was a restoration done of Nothing But A Man [1964]. At that screening, I met Jake Perlin of The Film Desk who really turned me on to the Library of Congress's role when a film is in their registry, and their investment in making sure that film is accessible and preserved. He introduced me to a contact at the Library of Congress and I began meeting with them about having [Spook] restored with some of the latest technology. That process started at the beginning of ‘21, and we went through the whole grant submission process. The master was maintained in a vault by my father the entire time and then, after my father passed, we continued to keep it in the vault.

ZSC: I heard that when the film was initially released, and suppressed, one print was kept under a different name, and that's how they were able to safeguard it. Do you have any other information about that?

ND: I love it. There are a lot of stories and myths and different iterations of everything. But he did keep the film in a vault after receiving it back from United Artists—that was a whole different story, but it was always under his name in this particular vault in California.

ZSC: Now that you’ve mentioned Nothing But A Man, it’s worth stating that your father was an amazing actor and a pioneer of Black independent cinema. You can feel this love of cinema throughout The Spook Who Sat by the Door. Old plantation films and John Wayne westerns are mentioned in the film, and in the book there's a reference to Italian cinema that says Antonioni was making a film depicting the Chicago riots and cast Marcello Mastroianni in blackface as the lead. It's a funny bit of satire. I'm wondering if both of you could speak a little bit to the appreciation of cinema that you saw from your fathers.

NP: I would say, maybe surprisingly, that Sam Greenlee wasn't really a lover of Hollywood. He had very serious opinions about Hollywood in general. And they're very strong opinions. I want to repeat that because I don't want to say the words that he said exactly. I think that his love of writing his stories and putting them on paper was more what he was interested in, and the opportunity to then put the story on-screen with Ivan Dixon was certainly a great opportunity for more people to hear his message.

If he was here he might have a different response, but I think there was a lot of frustration with stereotypical roles that Black men and women were playing, especially in Blaxploitation movies, so I think he probably wanted to avoid that. I think Ivan Dixon does a great job of this, elevating Black stories by showing someone who was not just cool—Dan Freeman is very cool—but also incredibly intelligent, and that's not usually our stories.

ND: I’ll mention my father was an avid reader and book collector, and the book really resonated with him. When Natiki says Sam had some strong thoughts about Hollywood, so did my father. The only difference is he was working within that industry and had some different experiences there. But you will notice, through my father's acting and directorial career, the type of roles and stories that he took on. He was also very much about elevating our people.

He did love films though. He grew up in Harlem and he used to go to the theater every weekend and be in the balcony. He did love film, but he also respected film as an important vehicle or medium for communicating messages. And similar to Sam, he was all about telling stories of substance: real stories about real people. That was a lot of his attraction to the book, but it was also something he wanted to say in film about the political atmosphere of America at the time.

ZSC: This film is an amazing contrast to Hollywood’s depiction of Black people. I think that because it was an independent film and they were able to take certain liberties, many of the themes still feel very current and powerful. I was watching Infiltrating Hollywood [2011], the documentary about the making of this film, and you can tell that there was a huge toll trying to get it out, but Sam Greenlee does say, “I paid my dues, but it was worth it.”

ND: I would add that it was a constant fight for my father throughout his career in terms of representation, and even in the making of this film getting the finishing funds from a major studio. There was a balance there in how you maneuvered and operated while keeping the integrity of the piece.

One quick comment about the risk of doing this, I'll share a story that I think relates to what you quoted out of the documentary. You can imagine it was a huge risk to make this film. For Al, Lawrence Cook, who played Freeman, it took a tremendous toll on his career. He was a family friend and he often said he had no regrets. It was his masterpiece and he was masterful in it. For my father, it was about the achievement of doing it and getting it out there. He had some issues immediately following in his career, but fortunately it didn't derail his career completely—it was worth the risk. And for me, I think it's about continuing that legacy and making sure the book and the film are still around because the messages are, like you said, so relevant today.

ZSC: It makes me think of one of the themes that Dan Freeman brings up in the film, this idea of “freedom dues” and the price you have to pay to get this freedom, that is much more than emancipation or just not being locked up in jail, especially when you consider the Black ghetto as a kind of internal colony. The film provides this playbook on trying to achieve that freedom. I'm curious about what your fathers would say, or your perception, of what that freedom actually looks like—what that vision was, or what we're still seeking in revisiting the film today?

NP: That's a great question because I think that is one of the things that I loved about the book growing up. It wasn’t just about seeking a freedom that was external without physical shackles, but more about internal freedom. A major theme of the Black Liberation Movement was freeing our minds, so to speak. Being able to be free thinkers and to be able to move about freely, to create and do all the things that we do really well that are exploited still today.

I certainly couldn't say what my father's perspective was on that, I'm sure he has a lot to say. But for me, I think Dan Freeman's vision in that moment is more about our ability to freely express ourselves and have fulfillment, the so-called “American Dream”—to be one hundred percent who we are and who we're divinely designed to be. It's a little abstract, but it's definitely something I think my father aimed for in his personal journey. He never wanted to work for anybody or have to check in with anyone. For him, that was success and some level of freedom, not fully, but it’s an expression of not being able to be restrained or have to be defined by someone else's perception.

ND: I definitely can't speak to what my father would say freedom would look like either, and I don't even know that he would have the complete answer to that because his life was about a struggle. We talked about the struggle within the industry. These are two men that were born in the ‘30s. Their experience just speaks to continually wanting that freedom of thought, that individuality, that respect.

I mentioned, at the premiere, that he is often quoted saying the film said all he wanted to say about race. You could spend a whole lot of time dissecting all the different aspects, but it did hit on the thoughts he had on race at the time. He's often quoted also as saying it was a fantasy for him; a fantasy in the sense that he did not necessarily know if it was attainable, but it was a fantasy for any man with his frustrations that this could happen.

ZSC: It was amazing how many people in the theater on Friday hadn't seen the film before, and I hadn't seen it until I saw that it was coming up at BAM—it really blew my mind. It is such an incredibly rich, detailed film. Also, largely because of the conventions of the spy film, there's so much for you to notice upon re-watch. I'm curious if you both still notice new things when you see it. If so, what did you notice last time?

ND: Absolutely, I always see something new. I don't know if I catch new lines, but certain favorite lines get more brilliant every time I see it. I've seen it on large screens before, but this screen was incredibly large. And the restoration is so nice that you really get a different depth—the shots of them in the dark, the movement of the guerillas in the riot scene, and the jumping from roof to roof. But there's so many storylines and so much that's being said. Each time, something else stirs me in terms of the Black experience.

NP: Yes, same for me. I've seen it many times on DVD, but for me it's almost like seeing it for the first time again. Funny story, my dad used to send me copies of The Spook Who Sat by the Door on DVD for my birthday every year. I have no idea what that was about. And then, when my daughter was born, she also started receiving copies. [Laughs]

ZSC: Little plug. [Laughs]

ND: It’s called distribution. [Laughs]

NP: We laugh about it at home a lot. I don't know if he was trying to store up copies or what; it was actually masterful if that's what was his intention. But being able to see it this way felt fresh. I was sitting there like everyone else, with my eyes popping out of my head as though it was the first time I ever saw it. This is a very layered movie. You might focus on one character at a time because each represents a different part of our experience.

ND: I agree, you can look at it from each character's perspective each time. Paula Kelly as Dahomey Queen, Paul Butler who was an excellent theater actor, Al Cook started in the theater as well. These performances are phenomenal. And then upstarts like David Lemieux as Pretty Willy. A lot of thought was put into each of those characters. All the nuances, down to Joy taking off her wig and putting it on the white wig holder—so intentional—even the set decoration. You need to see it more than once and I definitely recommend seeing it on the large screen.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door runs August 23-September 5 at BAM. Author Adam Shatz and Film Comment editor Devika Girish will be recording a live edition of The Film Comment Podcast titled “The Rebel’s Cinema—Frantz Fanon on Screen” following the 7 PM screening on August 31.