Between the encyclopedia and the algorithm lies Mungo Thomson’s Time Life. The LA-based visual artist uses the titular encyclopedia collection as raw material, converting the printed pages into nine videos presented in a theater-like display at Karma. Through digitization, editing, and finally animation, Thomson simulates the hypnotic hyperspeed of archival scanners to capture the migration of information across technological epochs.

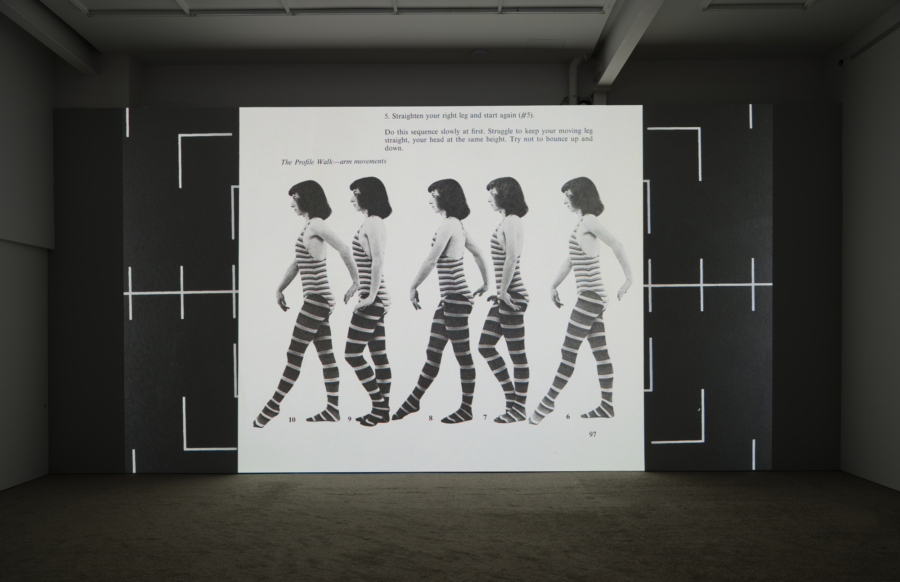

Thomson’s video-essays filter distinctly human creations and observations through a book scanner’s mechanical gaze. His subjects are grouped into video-volumes to index diverse subject matter, like the books themselves: a vast seashell collection, a hummingbird in flight, life-drawing models, wheel thrown pottery, historical artifacts, mimes, geological formations, a burning candle, and a guitar manual. The scanner’s hyperspeed (eight pages per second) corresponds to a frame rate sufficient to trick perception into construing motion from stillness, as in flip-books and stop-motion animation. Pages retain their processed aesthetics—appearing sideways, cropped, or atomized through proximity, with the scanning bed at times visible at the edges.

In Volume 5. Sideways Thought, Thomson presents anatomical studies intended for figure drawing. Images of the human body, captured from numerous angles, are stitched together, transforming 2D representations of three-dimensional figures into digital, 3D scans. The resulting video presents a disorienting dance of anatomical forms, as static illustrations adopt an uncanny semblance of motion and depth. The bodies are systematically reduced to visual data, exposing the figures’ lifelessness as Thomson’s technique attempts to animate them. The scanner’s gaze becomes almost haptic as it reaches across layers of meditation—grasping for the body through the page through the screen.

Thomson’s scanner both destructs and preserves. The machine literally destroys physical books by removing pages and breaking spines, sacrificing its physical form to its digital afterlife. Yet Thomson inverts the scanner’s process of digital sublimation, looping the apparatus back on itself such that the book’s dissolution into pixels paradoxically heightens perception of its materiality. Pages move across the screen, their page-ness somehow more pronounced in their digital state than in their physical form. In Thomson’s digital alchemy, dematerialization becomes a strange new materiality.

Time Life occupies a threshold between analog and digital worlds, enacting a distinctly generational critique while engaging long-standing artistic dialogues around reproduction and representation. The project operates within and beyond a lineage of Pictures Generation artists, who emerged in the late 1970s to critically examine how print media archives construct and circulate meaning. Thomson’s scanner-as-filmmaker apparatus updates their concerns for an era where archives exist as both physical repositories and digital information networks. Where artists like Sherrie Levine appropriated photographs and artworks to interrogate authorship and originality, Thomson extends her strategies into durational and procedural spaces beyond the reach of analog methods.

Thomson insists that material-digital translation remember its origins even as it passes beyond them. In allowing the mechanized process to itself generate meaning, Time Life moves beyond critique of representation and into a technical constitution of experience; here, technology doesn’t reproduce reality, but actively produces new sensory regimes. By positioning the scanner as both creator and destroyer, he suggests that material-digital translations produce gaps that cannot be incorporated across informational networks—gaps to be bridged by something like art.

Mungo Thomson: Time Life is on view through April 26 at Karma Gallery.