...if the great Canadian comedy ever gets made, John Paizs might be the one to make it.

– Jay Scott, Toronto Globe and Mail, 1985

There is a paradox at the heart of John Paizs’s Crime Wave (1985): for a comedy about the agony of writer’s block, there is a stunning degree of imagination on display. The violent death of a music icon tribute player becomes a media circus. Corporate pyramid scheme killers are slaughtered by cops at their industry awards. Self-help racketeers drive themselves to suicide. But those are just beginnings and endings of stories left unfleshed.

Steven (Paizs himself, silent for the duration) is a screenwriter of “color crime movies” who cannot write the middles of those stories. He takes up residence in the garage attic of perversely ordinary Winnipeg suburbanites, befriending their pre-teen daughter (Eva Kovacs) in a companionship less Lolita-esque than innocently limerent. Only able to write by streetlight, Steven’s torturous, fruitless nights eventually lead him on a desperate quest to decipher this one-word solution from a mysterious stranger: twists.

Surrounding the simplicity of this core story is a frenzy of narrative fragments that depict the afterworld beyond Steven’s block as a homemade Technicolor dream (or nightmare). Paizs relentlessly employs a kinetic language of 1950s educational films and Z-grade genre fare—as well as extensive world-building production details and practical effects—to illustrate the cartoonish pandemonium of artistic flow. Crime Wave—reportedly made "for about 35 thousand [Canadian dollars], shot on weekends over 18 months with an all-amateur cast and a crew of three”—stands firmly outside the considerably less vibrant low-budget style of most independent film of its era.

But some diamonds never escape the rough. After debuting to acclaim at the 1985 Toronto International Film Festival, Crime Wave’s momentum was essentially derailed. Paizs, ever the perfectionist, happily complied with the distributor's desire for a new ending. The film was purchased but inexplicably shelved, never released theatrically beyond a handful of local art-house theaters in Canada. For decades, it was only available on a hard-to-find VHS, retitled The Big Crimewave to avoid confusion with the wacky Sam Raimi/Coen Brothers horror-comedy from the same year. Though its impact was muffled at the time, Crime Wave is now considered central to the “prairie post-modernist” movement—a term coined by critic Geoff Pevere—out of which many of Canada’s most unique film artists have emerged. A previously lost 16mm print of the film, including the original ending, will screen at Spectacle Theater this weekend, with screenings of a new digital restoration to follow next week. It shows as part of the series Tales from Winnipeg presented by Glasgow/Bristol-based Matchbox Cine.

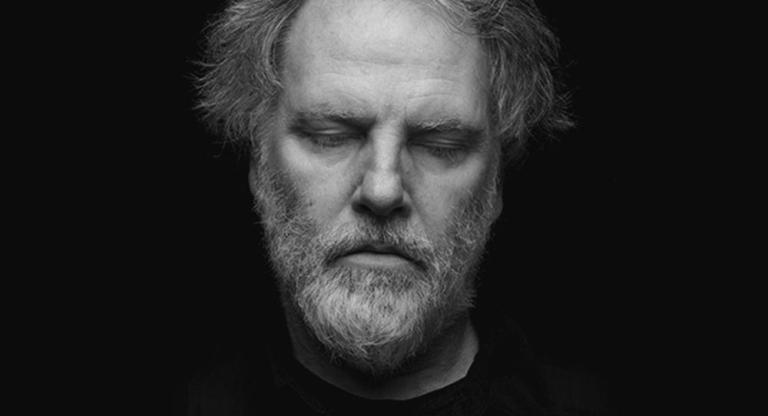

I had some questions of my own for Mr. Paizs, reached via email.

Sean Benjamin: From what I’ve read about your screenwriting process, you seem to have been a fairly prolific writer: I read that Crime Wave was culled from two previous feature scripts, for example. Despite that, writer’s block must be a central theme for a reason. Were you like Steven? Do you—or did you—have a particular issue with middles rather than beginnings or endings? It would seem that much of Crime Wave could be considered “the middle."

John Paizs: I had a bit of writer’s block just before starting on Crime Wave. I was a bit gun-shy about starting a new screenplay because the previous two I’d written didn’t work out to my satisfaction. But once I got going on Crime Wave, it came fairly easily. Though all my screenplays did back then, to be honest. With each, I just made it up as I went along, and when I got to where I’d write “The End,” that was pretty much it. I almost never revised. Just would type it out, and make a few changes then. It kills me when I think back on that now, how laissez-faire I was about it. And sometimes the thing came out as having a more traditional kind of dramatic structure, and sometimes it came out more like Crime Wave, which is more episodic. But yeah, that was my process back then.

SB: Did you have any specific postmodern or self-reflexive narrative touchstones that influenced Crime Wave? I’m thinking specifically of the scenes with characters crossing between Steven’s various beginnings and endings to interact with each other.

JP: Quite possibly Fellini’s 8 1/2. I’d certainly seen it before writing Crime Wave, and it may well have influenced me, subconsciously anyway, in that regard. It does have similar kinds of fantastical interactions. And hey, it’s also about writer’s block!

SB: I’ve read about your feelings on like-minded then-contemporary works like Blue Velvet (1986) and others, but I’d love to know your opinion specifically of Sam Raimi's Crimewave (1985), not just because of the name confusion but its similarity in exploring B-movie tropes.

JP: Truth—I’ve never seen it. Though I had the feeling at the time that it lacked the edge that my Crime Wave has, and that, Raimi’s camera shenanigans aside, it was probably a pretty normal movie ultimately, and I wouldn’t be interested in it. But yeah, for sure, the timing of its release sucked for me, as the title of mine had to be changed in the US in order to avoid confusion with it.

SB: I’m a big fan of the fairly small number of classic-period noir films produced in color. Was this subset influential on you and the notion of “color crime movies” as a theoretical genre?

JP: I’m sure it was! I loved the Technicolor look of Rear Window [1954], Leave Her To Heaven [1945], Niagara [1953]… How exciting! The intensity of colour against inky black shadows! Dreamscapes turned to nightmares, no escape! These were worlds I wanted to create myself, and I said as much, through Steven, but also in how I coloured his own world, in Crime Wave itself. He was living the dream!

SB: Much of the design in Crime Wave is very well-executed, and I’ve read about your comic book history as well as references to a background in graphic design. Did you go to school for design? Or were you ever employed in that role?

JP: I did go to art school. I have a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree. And before that I worked for about a year as an animator on TV commercials and even some Sesame Street cartoons (French Canadian ones). I was just out of high school then. It was initially my ambition to either be an animator or a comic book artist, but then while in art school I decided to concentrate on live-action filmmaking instead.

SB: Can you tell me a little bit about the specific technical work done on Crime Wave? Where were the optical printing / matte / graphic effects executed? Did you do those yourself or have other post-production help?

JP: I did all the graphic effects myself, often using my animation knowledge to figure out ways of executing them. But everything I did was really old school: double exposures, glass paintings, miniatures. Steven typing at night, seen in his garage apartment window—the garage there is a miniature. The town of Sails, Kansas—that’s a glass painting. The letters spelling “Twists” floating in though Steven’s apartment window at night—a double exposure, the letters filmed on an animation stand. There was no optical printing or matte work done at all on the movie.

SB: Can you relate the story of the $2000 camera accident (depicted in photos and an audio recording in Crime Wave) at the National Film Board of Canada that happened during the making of your previous short Springtime in Greenland (1981)?

JP: The shot needed Corny Blower’s muscle car to race up the street directly towards the camera, then make a hard right in front of it, and into the driveway of the suburban home where the barbecue party was. I was behind the camera, which was low on a tripod, at the centre of the sort of T-intersection there, just in front of the curb. I was crouched there. I waved for the driver to come on (he was a friend of mine from high school, and it was his car), and what happened was that he was coming so fast he couldn’t make the turn. His brakes locked and he just kept coming straight. I just had time to roll out of the way, knocking the camera over as I went to hopefully get it out of the way, too. Instead, the skidding car clipped one of the tripod legs that had lifted off the pavement, spinning the tripod around, and smashing the camera into the pavement. The car then took out the streetlight that had been behind me, on the boulevard, before coming to rest up there, the streetlight pole lying horizontally on top of it. It was insane. It was a miracle no one was badly hurt or killed—mainly me, as I was the one directly in the car’s path! Next thing the police were there. In the end I paid for the repair of the camera (which I had borrowed from the National Film Board of Canada) and also half the insurance deductible for the car repair. But yeah, it was a supremely stupid thing I did there, and I really have no excuse for it except that I was young and supremely stupid.

SB: Did you keep in touch with lead actress Eva Kovacs? I understand she became a TV news anchor?

JP: Oh yes, for sure, we’ve kept in touch over the years. It’s always wonderful to catch up with her when we have the opportunity to visit. And we’re also friends on Facebook, so we regularly get to see each other’s status updates there, which is great. And yeah, she became a TV news anchor, which is so cool. I’m so proud of her.

SB: One of my most curious questions: did you buy all of those original noir posters that hang in Steven’s garage attic bedroom? They must have been a lot harder to find in 1985 than today on the internet.

JP: Actually they all belonged to a local animator in Winnipeg that I knew. He had an amazing collection of them, and also movies and movie trailers on 16mm. Where he got them all from exactly, I don’t know. I could just imagine various sources in the US. And actually, it was his noir B-movie trailer collection that he showed me one night that inspired the various beginnings and endings for Crime Wave!

SB: Can you give me any examples of films—or other works of art—since 1985 that you feel have come closest to the vision you crystallized in Crime Wave? Do you feel you have any artistic heirs, so to speak?

JP: You know, honestly, sometimes I think I’m the worst judge of this kind of thing. But I can tell you one story, though, about one particular film—a very well known one—that may have a bit of Crime Wave in its genes. I’ve told this story before. And keep in mind, this is 100% speculation on my part, I’ll never know the truth of it, but I like to think it may be true. Back when I had just finished the new ending for Crime Wave, my distributors sent the cut to the Coen brothers to get their take on it (this happened more or less behind my back). My distributors thought that they would “get” Crime Wave (having recently made a splash with the new-wavish Blood Simple [1984]), and could possibly offer some useful feedback. Nothing came of it that I know of, but a few years later the Coens came out with their own blocked screenwriter comedy with surrealist overtones, which also had its own made-up movie sub-genre, the wrestling picture, and of course I mean Barton Fink [1991]. Coincidence? Like I said, I’ll never know, but yeah, that would be all right by me if it wasn’t.

Crime Wave screens tonight and tomorrow, December 10 and 11, at Spectacle on 16mm as part of the series “Matchbox Cine Presents: Tales From Winnipeg.” It will also screen in a new digital restoration on December 15 and 23.