In 2006, I attended a screening at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles of three short films by Guy Maddin, followed by a Q&A with the visiting Canadian auteur. When the lights came up, Maddin reappeared holding a pizza box, and proceeded to wax poetically about his process, influences, and peccadillos.

It was an optical exercise in hilarious contrasts: the work deliberately reminiscent of a distant visual past, the man as real as life, friendly and effacing, enjoying a pizza. I was expecting a caricature—riding crop, monocle, jodphurs and a light meter—and saw, instead, a refreshingly mortal soul. The aesthetic and metaphysical qualities of Maddin’s work continue to mesmerize me: the dreamy use of montage and elaborate set designs, the thematic whiplash from pathos to ribald humor. I’ve awaited every new release with the kind of fervor reserved for Marvel superfans or New York sneakerheads.

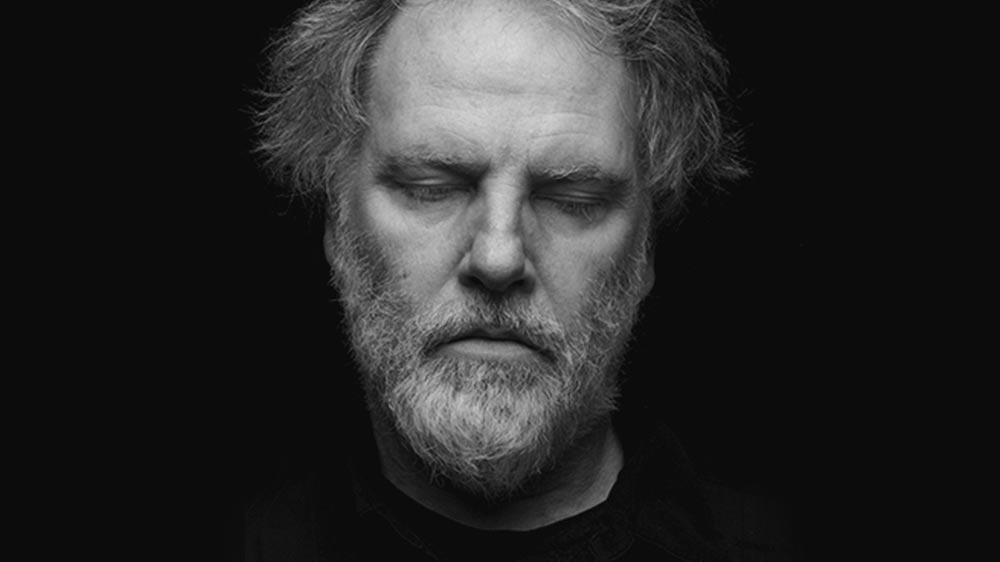

Last year, I had the pleasure of virtually meeting Maddin during an “Occult Home Evening” Google Hangout with Toronto-based critic Adam Nayman and fellow Screen Slate contributor Danielle Burgos. On one such occasion, Maddin joined us on a whim—over several happy, tipsy hours we discussed esoterica, read tarot cards, and shot the breeze. Five months and several psychic eons later, under the auspices of Maddin’s Criterion Channel retrospective and 65th birthday on February 28, I caught up with this slightly housebound, perennial-boy genius to probe the earthy and ephemeral elements that inform his work.

Our conversation below has been edited for clarity and concision. Special thanks to Ben Easton for transcribing this interview:

—

Caroline Golum: Happy almost birthday! You’re a pensioner now! What’s it like turning 65 in a pandemic with a retrospective on the Criterion Channel?

Guy Maddin: This retrospective came along at a time when I could sure use it. Not that I need to be endlessly caressed but, you know, this has been a long COVID winter. All of a sudden, it’s pretty great to be on the best possible platform my films could have. That just came out of the blue.

It’s occurred to me that all along this body of work I’ve been amassing isn’t a varied collection of my individual obsessions during any given year over the last thirty years. It’s just been one big continuous towel: a continuous diary film. It’s just an ongoing portrait of who I am at any given moment. It’s kind of just a psychological EKG, some sort of intricate graph paper sort of unfurling itself with each passing title.

My obsessions, my immaturities. It’s just like watching a picture of yourself age; I’m Dorian Gray watching these movies not get older, with my own wrinkly face superimposed over them in increasing embarrassment. I think this metaphor is falling apart under its own weight.

You’ve hit on something that’s very true — not just of your work, but for any artist who works for years at a time. Even if you were making an aesthetically and narratively different film every time, if you veered from one genre to another, there would be a perceptible sense of yourself in it. There’d be… not an odor, but something redolent of you.

Certainly, an odor. I remember when Steve Soderbergh came out with his first hit movie, Sex, Lies & Videotape, he did a lot of really good interviews; he proclaimed that he hoped to be a filmmaker with no recognizable personal style from title to title. I was just starting. I’d made my first feature only, so I was filled with hope that there would be many more. I remember thinking, “Oh god, no! Don’t erase your personal style!” That’s the fun part in watching directors, even lesser-known directors — Robert Siodmak or something like that, where you can see that Siodmak touch.

People mention you in a similar breath as Eisenstein, or Von Sternberg, or Browning — filmmakers who pushed the limit of what cinema was able to look like and evoke at that time.

Well, those are ludicrously flattering comparisons. People might be saying I was inspired by those geniuses. Particularly Von Sternberg, who I was watching rabidly, just before and soon after I first picked up a camera. I love that his movies with Dietrich weren’t even movies — they were something else, tableaux with unbelievably mannered performances. They do have plots of course, but it’s those performances that are so strange. There was an inherent perversity coming outright from Morocco and The Blue Angel, his first talkies. All of a sudden, they clearly head in another direction than all of the other movies coming out of Hollywood. That was thrilling to me, that someone was just ferociously making these things that were just so fiercely his own. I find Abel Gance the same way, his politics aside; he’s probably some sort of anti-Semite. Crazy all the time.

Well he’s French, so —

I remember watching one of his earlier silent films and a friend of mine saying, “So this is what editing could have ended up like if Gance’s films were really successful.” It was like he was editing in a different language. He was cross-cutting between night and day, as if they were happening at the same time, just ignoring conventional time-space continuums. It was really exciting — and doing it in such a way that it called attention to how it was done. You could almost see his fingerprints all over the thing.

It was exciting to me, because I guess I knew I would never be a very highly polished filmmaker — that I loved other filmmakers who had become legends in spite of having their fingerprints all over things. I thought okay, maybe there is a chance for me to have my own highly idiosyncratic style penetrate some sort of public. Ultra-low budget as well. Those people were all working within an expensive system. Not me. I really have been working the margins, and I’m comfortable there.

You say Abel Gance’s fingerprints are all over his work. Your fingerprints are all over your work, and that's its strength — like you said, a continuous video diary. There’s something about it that resonates with people: they’re interested in you, they’re interested in how you see the world, and how that materializes. You strike me as a very singular artist, but obviously your work from a technical standpoint does require a considerable amount of collaboration.

I’ve been working with an ex-student of mine, Evan Johnson, and his brother, Galen Johnson, very closely. Between the three of us, we wear all the hats necessary to make a movie: graphic designer, sound designer, music composer, editor, screenwriter, cinematographer, the whole thing. We call ourselves Development Limited, and we have a very cheap office where we meet every day. The last full-length feature we made, The Forbidden Room, Evan and I were co-directors on.

If you get a good collaborator, they’re coming up with ideas that you would have come up with if you were just a little smarter, or just happened to think of them. You’re all pulling in the same direction, but you’re discussing things to solve a problem. We’re all temperamentally attuned, and we make each other better. I’m older than my two co-directors, so maybe they get something from my experience. But I get something from their youth and their technical savvy. We turn each other onto things all the time. It’s really almost like being those great guys in Fellini’s Vitelloni. I feel like a twenty-something again, just discovering and playing around in the landscape of my hometown as a youth, where everything I feel vibrating in my body feels like the future again.

You’re in Winnipeg right now, but the last time we spoke you were in Toronto. Winnipeg seems very lively when you’re outside of it, versus your version of it, and your work is this continuing narrative. I want to know about these other through-lines and these other diary entries, if you feel comfortable speaking more about that metaphor.

One of them has been me trying to sort out why I am the way I am — and trying to make it interesting for viewers. I don’t actually couch it in those terms: why is the director the way he is? It’s paying attention to my dreams, because my dreams are always trying to tell me something. About five years ago, I passed my dad in years and weeks and days lived … It was the day I started a new job at Harvard, and so I thought, “Oh, how lucky I am, instead of dying like my dad did on this day, I’m starting this new job for three years.” I felt really blessed.

I’m really haunted in my dreams by guilt and by people returning from the dead. I really love those dreams. I’ve used episodes from my dreams to help me write scripts, and I continue to do so now that I’m working with Evan and Galen. The most recent film that we have in our filmography is a centennial tribute to Fellini — we came up with the idea of using Fellini’s dream journal, and just shooting some episodes from his dreams, and making that a centennial tribute. But we found out that his dreams are copyrighted, and we couldn’t afford the time or the money to pay for his dreams. So we dipped into our own dream journal and ascribed to Fellini our dreams — Evan’s dreams and my dreams.

They were kind of Fellini-esque anyway: we have the same obsessions and concerns and melancholic bugaboos. My entire career, even now that I’m working with other people who are other people, has still been a diary — because it’s now a diary that involves these other people as well. My dreams get their dreams all over them, like peanut butter and chocolate. I’m just finally figuring out what makes people tick. Filmmaking is very therapeutic, especially if you make films about things you’re obsessing on. If you make a film about something you’ve been obsessed with for a while, the film project will cure that obsession because it just reduces everything to units of work.

You have to take those obsessive feelings and try to put them into words or images, and then you have to schedule them and cast them and find locations and build sets, and then shoot them, and edit them, and sound mix them, and then talk about them during Q&As at festivals. I think they were like breaker switches that I had to throw whenever things became too much, and I had to keep turning things into stories … I’ll tell you a story about something and the emotion seems to go out of it. It becomes a story instead. My mom actually just died a couple weeks ago...

I’m so sorry. I remember she—

She was 104.

You mentioned it the last time we talked. You said that she was alive at 103 or 104.

She was 103 then. She turned one hundred and four, got COVID, and beat it! But then she just passed away. I phoned the care home. I wasn’t allowed to go in — I hadn’t seen my mom in a year. I asked the nurse how my mom was doing, and the nurse misunderstood me and there was a language problem. It took her about five minutes to convey to me the fact that my mom was dead — that she’d been dead and they forgot to phone me. I couldn’t think of anything to say, I just said, “Could you tell me what her last meal was?” And this nurse said, “Yeah, half a can of Ensure.” And then she said, “Okay, have a nice day,” and hung up.

So that night, I went out and bought a can of Ensure and dumped half of it down the sink, and finished my mom’s can of Ensure and called it a day. I still haven’t received confirmation from the funeral home that they received her and cremated her. I’ve already had so many dreams about her wandering around, maybe growing in strength and even in height — I can picture her sort of shaking a FedEx truck until a crate of Ensure slides out.

Do you keep a dream journal? What’s your method?

If I have a dream I like, throughout my life I will write it down. And writing it down means I don’t have to read it again — the act of committing it to paper commits it to memory. I kept a written diary for a long time, which was half-dream journal kept in that fashion. I just kept it on my nightstand and wrote in it first thing in the morning, as much as I could remember of the dream I had. Occasionally there was another half — it was one and a half diaries, a sesqui-diary. Sometimes it actually was an account of what I did that day, which I would write at bedtime. Not that often. But the dream journaling … it’s frustrating. Evan [Johnson] keeps a dream diary and it sure came in handy when we were making The Rabbit Hunters. I still keep one on my night table.

I’ve had dreams in the past of relatives who’ve passed away, or ex-lovers, where you have almost an absolution or a forgiveness. The feeling that they confer a benediction upon you by dint of fact that they’ve shown up. I struggle with determining how much of that is manufactured by detritus left in my subconscious, and how much of that is actually some sort of contact across an ether. How much of it is truly a part of this world, versus another.

When I think of how much of my life I’ve spent just living in my head and traveling back and forth in time, it almost doesn’t matter whether that was real or day-dreamt, or dreamt. It just doesn’t matter. That’s all the emotional material that’s gone into making me, and making the people I love around me even moreso. It’s not as self-centered as it sounds — it’s the people I care about. My dad died in 1977, 43 or 44 years ago, and I feel like I know him better now. Not just because I got into his shoes and was able to empathize a bit more as I got older, but because I got to know him in dreams.

I actually do believe, and some neurologists will back me up on this, that you remember absolutely everything that’s happened to you … it’s just a matter of being able to access it. But I think the dreams I’ve had have enabled me to have access to things my waking mind can’t get at. They’ve shown me things, and they’ve given me way more evidence than my waking self could ever collect in building a profile of my father, or my grandmother, or my aunt, or my dog. I just understand them, not only in ways that I could put into words, but in my heart too. There has been a cumulative strengthening of the relationships, rather than a fading into oblivion.

A lot of your films are about death, but there is this weird Weimar-esque duel between death and eroticism. They’re these two taboos that are entwined. When we met initially, you told a really beautiful story about a séance you conducted while you were making a film with Geraldine Chaplin and Jean Vigo’s daughter.

That's called Lines of the Hand. We shot a little bit of it, or we edited a little bit of it, and it’s on the Criterion Channel. It was edited together in a weird way. Lines of the Hand was written by Jean Vigo, and then he never shot it. As you know, he died young – at age 29 I think? And left little Luce. When his widow died a couple years later, little Luce was an orphan by age seven. She never got over it, even in her eighties. If someone nearby honked a horn loudly, she would go “Maman!,” and call for her mother still, at age 80. She thought of her father a lot, and she created [the Prix Jean Vigo], which she then adjudicated herself and gave out to the best young filmmakers’ work. To say she cared for her parents a lot, that she made an altar to them, is an understatement — her apartment was a living shrine to her father, and also to Charlie Chaplin.

There’s tons of Chaplin stuff in her apartment. And that’s because she knew her father loved Chaplin. And then in Zéro de conduite, his forty-minute short featurette, there’s the teacher that imitates Chaplin in there. Chaplin meant a lot to Vigo and meant a lot to Luce Vigo. And of course, Chaplin loved Vigo’s films as well. So both these daughters knew of each other, and they knew of each others’ fathers. When I put them together, it was because I thought it would be nice to make them join hands and make them go into a trance, supposedly. The trance was just to be faked for the public. I had them join hands and I kind of narrated, out loud, where I wanted the wind and the fog machine and the lights to be. I finally took my eye and pressed it into the viewfinder and noticed that both Luce and Geraldine were clutching each others’ hands with all their might, and weeping copiously — just sobbing.

All of a sudden, a big lump rose in my throat and a bunch of tears squirted out of my face because it felt like something real was happening there. It might have just been two people who loved their fathers connecting, and at that intersection creating an emotional intensity that they weren’t used to. I felt swept up in it somehow. It’s not recorded really, even though I had the camera going — it’s not there. It was something I saw with the naked eye, in combination with the camera. The way the film was edited, it follows more the lines of the little Vigo treatment rather than the story of what was going on in that séance, that fake séance. But it was far more powerful than any real seance could be. So I have a clear conscience about the fakery. It was really special.

You staged a séance and it ended up being more real than the kind of 19th century spiritualist seance — somebody tapping their foot, a bell goes off. There is a very palpable sense of energy that can pass between two people if they’re in a heightened emotional state. When we talk about things that are adjacent to our waking life or our real living world, we regard it with a certain skepticism because it’s so ingrained in us. Your work is such a flagrant rejection of that skepticism.

I think the skepticism serves a purpose. I think it’s analogous to someone intentionally delaying pleasure they could have, just to heighten it all the more. The skepticism is a way of not permitting this indulgence — not permitting it yet, not permitting it yet, you know? Putting a treat on a dog’s nose, but not letting it have it yet. You can think of all sorts of instances in which we delay pleasure.

The technical term for what you just described, at least in a pornographic context, is called “edging.”

I should have known that. I did know it — I should have just used the term already.

It’s a nice through-line too, to talk about skepticism as a kind of “psychic edging,” as a way of delaying pleasure. “Metaphysical edging.”

The idea of death as this kind of consummation – it’s a climax, right? The idea of skepticism being this denial of pleasure is very much a piece of that. In very much the way we reject dying and keep away from it, we don’t want to be near it, we’re afraid of it. I think it’s very brave of your work to engage with it to the degree that you do.

I can’t get past the thought of metaphysical edging… I guess I’ve been doing it. To hear myself talk about it, I sure sound self-centered — I sound like some wanking solipsist. Maybe I am. I always try to be honest about myself in the work so that maybe if viewers were honest about themselves, they’d stand a chance of finding themselves in the movie somehow. I don’t know if that’s ever really happened, but that was the hope way back at the beginning.

Getting back to this dream thing, it’s such a rich avenue. I like that this is emerging as a theme, because it wasn’t my intention. Your work exists in this kind of weird waking sleep, or this sleeping wakefulness: that feeling when you’ve woken up from a dream and for a second it’s real. There is that moment when you remember everything with total clarity… and then bit by bit, reality strips that away. Your work, to me, and to a lot of other people who gravitate toward it, exists both visually and thematically in this weird twilight time. I don’t know if that’s the intention or something that you’re aware of, if you’ve heard it from other people — does it sound right?

It’s exactly what I’ve been trying to do the whole time. I haven’t heard it enough. Trying to figure out if I’ve heard it in exactly that way. I feel that dreams are kind of honest in a way. Not entirely — obviously they’re not literally honest depictions of what’s happened. But there’s emotional truth in them somehow, somewhere, in there…. if you can sort it out.

When I was starting out as a filmmaker, I had this strategy. I knew I wouldn’t be technically proficient and my films would be very disjointed and discontinuous, and as woodenly performed or as performed without affect as Buñuel’s. Or with a super uninhibited affect, like Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou or L’Age D’Or, which is his most influential film in my viewing experience. I knew my films, at best, would be just cobbled together, cut and pasted, pasted shots of things that are elements of film — that they would never be a smooth surrender-inducing viewing experience for people. I felt my best chance was to make the subject matter in my movies my dreams, and the feelings I had in them, which are pretty raw sometimes. And just present them as dreams, without actually saying this is a dream. Just the way cinema’s always called a dream anyway.

So this is just a dream within a dream. And then every now and then, I’ll have a character who’s actually having a dream within a dream within the dream. In The Forbidden Room we decided — Evan, Galen and I — decided to nest dreams within dreams within dreams like Russian dolls. We got narratives that were seven deep and worked their way to the little idea in the center, and worked your way back out again. I don’t even think there’s that coherent a theme throughout that whole movie. Maybe just the characters’ anguish, anguished frenzy. It’s edited that way, this movie is a seven-layer dream dip. Each dream is unfathomable anyway.

Like I say, I’ve gotten to know my father better by dreaming about him. I wish I could revisit dreams I had forty years ago the way you can watch a movie from forty years ago. But I can’t. It would be interesting to see what my father was trying to tell me forty years ago in those dreams, a short while after he died, as opposed to what he tells me now … We’re pretty laconic. We just sit in our rocking chairs and look out at the lake now.