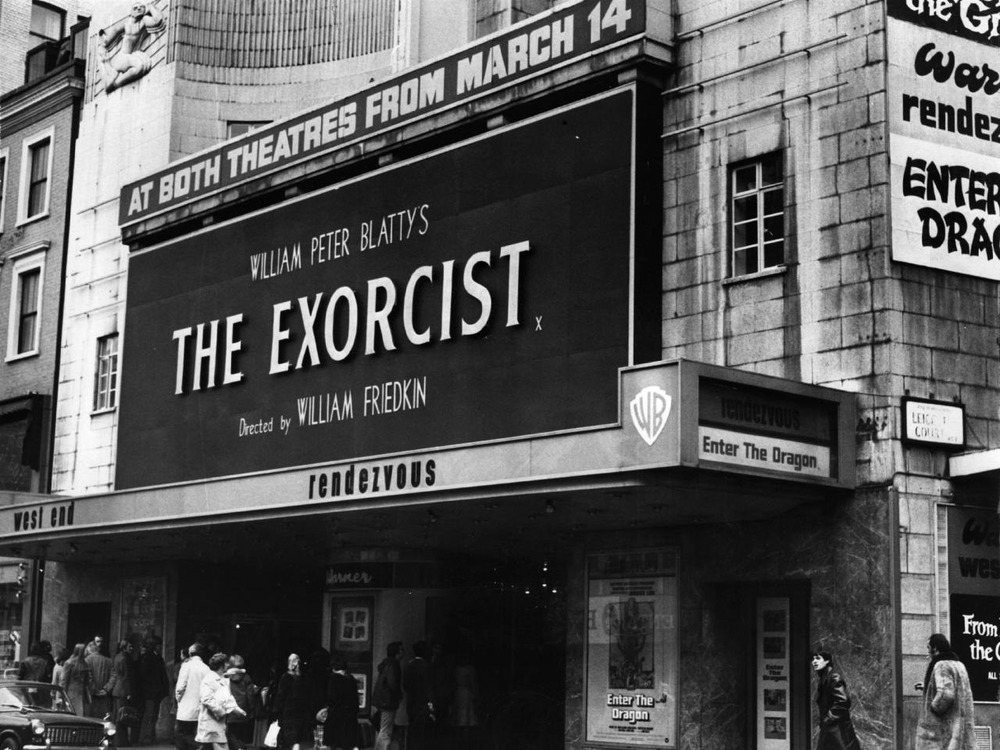

When spectators emerged from theaters after the premiere of The Exorcist on December 26, 1973, slack-jawed, loose-limbed, eyes red-rimmed—some perhaps with traces of vomit circling their lips—few could have imagined that a story about the demonic possession of a young girl would leave a permanent impact on film culture and on American society. Fifty years later, The Exorcist is the horror film par excellence, a lodestone to which every picture in the genre owes some grisly debt.

Based on the bestselling novel by William Peter Blatty, a devout Catholic, The Exorcist may not have registered so deeply with unsuspecting viewers were it not for the near megalomaniac vision of its director, William Friedkin, the New Hollywood rebel who died last August. Under Friedkin, whose obsession with audience reaction and commercial recognition acted as a counterweight to Blatty’s often orotund messaging, The Exorcist became a genuine pop-culture phenomenon while testing the boundaries of permissibility. That a Hollywood production managed to spark something close to mass hysteria seems unthinkable today, when blockbusters resemble little more than corporate agitprop.

While its impact was undeniable, The Exorcist was also mythologized to the point of distortion. That is the topic of a compelling and panoramic new book, The Devil Inside: The Dark Legacy of The Exorcist, published on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the film’s release. Long admired for his writing on boxing, Carlos Acevedo (Sporting Blood, The Duke) does more than recount the controversy that had filmgoers reaching for smelling salts. In challenging many of the myths surrounding The Exorcist (not a few of which, it turns out, were the handiwork of Friedkin and Blatty), Acevedo places one of the most scandalous films ever made in its proper cultural, historical, and sociological context. His book is long overdue.

Sean Nam: There have been a number of books on films from the New Hollywood era in recent years—from Midnight Cowboy [1969] to Chinatown [1974]—but few of them, if any, can be said to offer a truly critical examination of their subject. In general, film monographs rarely seem to rise above the level of appreciation. The Devil Inside, on the other hand, has a relentlessly analytical, even oppositional, streak. How important was it for you to maintain this stance in writing about one of the most ballyhooed movies of all time?

Carlos Acevedo: When you write about a film as revered as The Exorcist—particularly in the internet age, when fan sites cover every atom of minutiae—it can be a daunting task to uncover anything new. But for me, it was more a question of the “new” material simply being aspects of the film and its production that had been ignored in favor of puffery or glossed over to reinforce the mythic selling points of the production.

Appreciation has its place—and I enjoyed Shooting Midnight Cowboy by Glenn Frankel, just as an example—but the story of The Exorcist has long been in the hands of publicists, access journalists, superfans, and friends of the filmmakers. It was important to me to try to steer The Devil Inside away from a standard “making of” procedural, although there is certainly plenty of that in the book. It was also important to me not only to interpret or critique the film with a little less fanboy energy, but also to place The Exorcist in its proper historical context.

SN: It’s a refreshing approach for sure. The Exorcist was a phenomenon unlike anything else in American cinema, but it also didn’t materialize out of thin air. As you make clear in the book, the conditions were ripe within the movie business to welcome its advent.

CA: When critics talk about the social factors that may or may not apply to The Exorcist they talk about the counterculture, the sexual revolution, the generation gap, and so on, but they rarely mention how the film industry itself affected the film. As a prestige horror movie marketed to the mainstream, The Exorcist was unlike most other horror films in terms of publicity, production values, booking, and, of course, budget. It might surprise some to know that The Exorcist cost more than The Godfather [1972], Jaws [1975], Star Wars [1977], and most of the star-studded disaster films of that era, such as The Poseidon Adventure [1972] and Airport [1970]. More important, perhaps, is the fact that The Exorcist could only have been made during the tumultuous New Hollywood era.

You had an unruly filmmaker who was not working under the permissive auspices of something like BBS (the short-lived but scrappy, iconoclastic production company headed by Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider), but under Warner Bros., a venerable studio which would have fired someone like Friedkin a decade earlier, especially considering how the film took more than a year to complete and was over budget. This was not Dennis Hopper possibly pissing away $500,000 on a “youth picture”; The Exorcist was millions of dollars over budget. And while the New Hollywood had primed moviegoers to expect more violence and more sex, they were blindsided by the taboo-smashing grotesqueries of The Exorcist.

The Exorcist doesn’t resemble any other mainstream American horror film of the post–Rosemary’s Baby [1968] era, and only Don’t Look Now [1973], which was a British production, compares. On the fringes, there were creepy and often effective low-budget outings like Let’s Scare Jessica to Death [1971], Messiah of Evil [1973], Deathdream [1974], and others, but they were not on the to-do list of the average American.

SN: Speaking of providing context, you devote an illuminating chapter to the development of the horror genre. Again, there’s this notion that The Exorcist sprang out of the void, but in fact it had some pretty important and obvious pop-cultural precursors.

CA: To me, one of the most fascinating aspects of The Exorcist discourse, mostly in books, is that film does not exist. There are no movies referenced in these books. Similarly, the horror genre as a whole is absent, the New Hollywood is absent, Rosemary’s Baby is absent, and any precedents for, or influences on, The Exorcist—including novels such as The Case Against Satan by Ray Russell and films such as Mother Joan of the Angels [1961]—are absent. Of course, part of criticism is comparative, and yet rarely will you find films mentioned in any of the books about The Exorcist. In The Devil Inside, I try to contextualize The Exorcist, placing it against the cultural trends of its time. It was really a surprise to see that no one had mentioned the similarities between The Case Against Satan and The Exorcist or even mention the high-profile horror films that came out just before The Exorcist, such as The Possession of Joel Delaney [1972], The Other [1972], and The Mephisto Waltz [1971], much less smaller films like Season of the Witch [1973] or The Legend of Hell House [1973]. To completely disregard the debt Blatty owed to Ira Levin and Rosemary’s Baby seems particularly odd.

SN: It is made clear early on in your book that a great deal of the mythology surrounding the film is thanks to the pronouncements of William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty. Neither guy, I think it’s fair to say, comes out looking particularly good, not that they ever had lily-white reputations.

CA: Hollywood is not a place that produces the truth most of the time, and its denizens are often gleeful liars. Erich von Stroheim [and] Fritz Lang, are a few examples, with Orson Welles possibly topping the list. And, of course, nearly every memoir written by a Golden Age star is part fiction. But The Exorcist is unusual because it had two fabulists front and center: Blatty and Friedkin. Neither man had much interest in veracity, and both were obsessed with self-mythologizing. From my point of view, Friedkin was more interested in building a legend around The Exorcist, whereas Blatty seemed focused mainly on himself and on polishing his own ego.

One of his funniest claims Friedkin made about the shoot was that the crew filmed an actual archeological dig in Iraq for the prologue. That scene features dozens of fieldworkers frenetically using pickaxes, sledgehammers, shovels, and wheelbarrows—in July, no less—as if that would ever happen at a site where precious antiquities are located. The only thing missing in that scene is a bulldozer.

Other claims, which border on disparaging, included one about Peter Falk and Columbo. On the DVD commentary track of The Exorcist, Friedkin says the character of Columbo was ripped-off from [the homicide detective in The Exorcist played by Lee J. Cobb] Lt. Kinderman and that Peter Falk owed a lot to Lee J. Cobb. Blatty also insisted that Kinderman preceded Columbo. As I show in my book, Columbo was a TV and stage property that went back to 1960, and the hit telefilm that led to the long-running series aired in February 1968, long before Blatty began working on his novel. And Friedkin said that Falk was imitating Cobb in 1973 or 1974—when Columbo was already in its third season!

Throughout the production and its aftermath, Friedkin was Barnumesque in promoting the film, which put him in league with other exploitation hucksters of the ’60s and ’70s, such as William Castle and Herschell Gordon Lewis, except that Friedkin had a $12 million budget, world-class production values, a bestselling novel as a foundation, and a real command of his material. To play up the cursed production angle, Friedkin had no problem hinting that Ellen Burstyn and Blair had been mysteriously injured on the set, when, in fact, they were injured through his negligence and carelessness. During production, rumors of Linda Blair having some kind of mental breakdown ran in some of the gossip columns, sparking angry public responses from Blatty and Friedkin. But, to me, given how cynical the marketing was for this film, it wouldn’t be surprising to find out that Friedkin himself had leaked that story about Blair—for extra morbid coverage.

SN: In your telling, Friedkin and Blatty had a very contentious relationship. But they also seemed cannily aware that it was in both their financial interests to never let their disagreements go beyond a low boil.

CA: The discord between Blatty and Friedkin was real. Blatty was barred from postproduction and made a big stink out of it publicly. Worse, Blatty— who was the producer, after all—had approved a cut of the film that was re-cut without his knowledge. That Blatty and Friedkin maintained their friendship—with a few periods of estrangement between them—is remarkable. After all, Blatty never stopped criticizing Friedkin, sometimes with discernible condescension, and he insisted that The Exorcist in circulation until 2000 was inferior to his own preferred version. Even worse, perhaps, Blatty called Exorcist III [1990], which he directed, scarier than the original Friedkin version. The Exorcist alone cost Friedkin relationships with Lalo Schifrin, John Robert Lloyd, and Ken Nordine. But The Exorcist remained a money-making machine for decades, and the two men revisited it periodically to wring as much cash out of it as possible. Between them came novels, sequels (The Ninth Configuration [1980] had a loose connection to The Exorcist), several variations of the film for television and the home-video market, and in 2000 came The Version You’ve Never Seen. Had The Exorcist been PG, it might have produced a merchandise boom, the way Planet of the Apes [1968] and Star Wars did, with lunch boxes, action figures, playing cards, and models. In that case, Friedkin and Blatty may not have had to work so hard at tinkering with The Exorcist over the years.

If their working relationship was sometimes volatile, Blatty and Friedkin shared the belief that they were exceptional men who had to overcome the innate stupidity of the world. At every turn, Blatty and Friedkin depict themselves as underdogs up against it, only to prevail because of their almost superhuman qualities. Blatty in particular never stopped giving off an air of genius. No one wanted a novel about exorcisms back in the early 1960s, Blatty claimed. Yet a well-known publisher released The Case Against Satan by Ray Russell in 1962. No one wanted the hardback rights to The Exorcist, Blatty claimed. Yet Harper & Row won a bid for the novel. No one wanted to option the film, Blatty claimed. Yet Warner Bros., a major studio, paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for the rights months before the book was published. Not to mention [the British media mogul] Sir Lew Grade made a stingy offer on behalf of Shirley MacLaine. Friedkin, not that far behind in the self-aggrandizement category, made so many claims about his heroics that trying to sift through them is impossible, but sometimes the bluster was so clear that you realized he was joking. I never got that sense from Blatty, despite his reputation as a funny man.

SN: Indeed, you open the book with the fact that Blatty even fibbed about the original possession story that inspired him to write the novel.

CA: The “true” demonic possession story has never been given more than a cursory (and credulous) look in other Exorcist books. From 1971 to the end of his life, basically, Blatty lied about that case; he also omitted information that would have undermined his narrative—and, potentially, book sales. The most fascinating thing I discovered about the 1949 incident, through the work of Dr. Sergio Rueda, was that the boy involved had actually undergone an exorcism before the Jesuits arrived. It was a ritual performed by a folk healer, and it might have given the boy insight into how to frame his issues—which were psychological, not demonological.

SN: A film like The Exorcist does not persist for so long without being some kind of exegetical powerhouse. You argue in the book that The Exorcist is not a “formalist puzzle,” despite the cottage industry of postmodern interpretations devoted to the film contending that it is a subversive metaphor for this and that. In fact, you make it clear the film is notable within its genre for being completely devoid of camp and that, at its root, The Exorcist is a deeply conservative reaction to the social changes of the 1970s. Can you elaborate?

CA: Every cultural artifact is at the mercy of the prevailing critical orthodoxies of a given period: psychoanalytical, Marxist, feminist, semiotic, postmodern, Lacanian, queer—whatever. And The Exorcist is no exception. Filmmakers and novelists are often bemused or frustrated by runaway interpretations of their works, but Blatty left a loophole about his stated intentions by claiming, repeatedly, that his subconscious had been largely responsible for the novel.

Still, The Exorcist is nothing like Mulholland Drive [2001], or The Shining [1980], or 2001 [1968], or Last Year at Marienbad [1961]. Its overriding message is clear: “Believe—or else!” Along with that directive are a host of conservative themes about the nuclear family, materialism, and women. These themes, along with heavy-handed religious messaging, are more prominent in the novel. Because Friedkin was ten times the filmmaker than Blatty was a novelist (or a screenwriter, for that matter), he immediately saw that less is more when it came to The Exorcist, and produced a stripped-down, dynamic, at times elliptical version of the novel that left a few ambiguous points. It’s here where the most interpretation comes in, when Friedkin leaves things unclear. In fact, in 1974, when The Exorcist was a pop-culture phenomenon, Friedkin and Blatty begged Warner Bros. for permission to shoot a new ending, because the original ending confounded audiences. Warner Bros. declined, feeling that a record box-office should not be tinkered with under any circumstances.

I’m certainly not the first person to note how conservative The Exorcist is; Blatty was not a subtle writer, and his traditional values jump out on film, where compression gives them more power than they [have] on the page. A perfect example is a feminist reading of Chris MacNeil (the mother played by Ellen Burstyn). A famous, glamorous, rich divorcée who gets invited to White House lunches and has a staff of servants, Chris stands out as a symbol of women’s lib and the sexual revolution. Soon, however, she’s serving coffee and drinks to Kinderman and Karras, ironing Karras’s shirt after Regan vomited on it, and knitting downstairs while the men called in to restore the patriarchal status quo are battling over the soul of her daughter.

SN: The Devil Inside is rigorously reported and evinces a deep familiarity with the horror genre and history of low-budget movies. I understand you were a child of the New York City grindhouses of the ’70s and ’80s . . .

CA: I was a horror fiend until around my late teens, I guess. When I was maybe 10 or 11 years old I had already turned my back on the mainstream . . . instead of E.T. it was Q [both 1982]; instead of Back to the Future, it was Re-Animator [both 1985]. My brother took me to double features often, and I remember one was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre [1974] and Sleepaway Camp [1983]. I was also reading magazines like Fangoria, Cinefantastique, Deep Red, and Gorezone regularly. Fangoria and Cinefantastique, in particular, devoted dozens of pages each issue to the production of horror films from the past, which gave me some insight in how something like The Exorcist compared to its genre predecessors.

SN: Was that the period when you first saw The Exorcist? What was your reaction?

CA: I saw The Exorcist once as a kid and then years later on VHS when I was a teenager. Actually, when I was a kid, back in the ’70s and early ’80s, The Exorcist was rarely on TV. HBO aired The Exorcist in 1976, but network television didn’t broadcast it until 1980, when CBS paid $2 million for the rights. Like so much about The Exorcist, its scarcity was mostly about money. Keeping the film off TV for six years was a calculated effort to ensure that theatrical rereleases would reap as much cash as possible. The Exorcist was rereleased at least twice in the late 1970s, and its initial theater run was far longer than [that of] the average film: it was still playing widely in 1976. This was at a time when ancillary revenue was limited—no Blockbuster Video, no DVD sales, no endless cable channels. In the late ’70s, The Exorcist was available on BetaMax, VHS, and even LaserDisc, but those were expensive mediums and had limited penetration.

The horror films that seemed to be on TV every week were Psycho [1960], The Haunting [1963], The Legend of Hell House [1973], The Birds [1963], Burnt Offerings [1976], and various Hammer films. And every Thanksgiving WOR (channel 9) showed a monster-thon featuring King Kong [1976], Godzilla [1954], and Mighty Joe Young [1949]. So The Exorcist did not have that nostalgic hold on me that other horror films did that might not be considered in its class. As I mentioned, I saw it once when I was 10 or 11 and then I saw it again during the VHS era. I don’t remember being particularly overwhelmed by it either time. The movie I saw most often as a kid—which is a kind of horror film, I suppose–was Taxi Driver [1976]. I had a warped childhood.

SN: Some of the most shocking elements of The Exorcist have understandably lost their novelty in the ensuing years—for example, I’m not even sure a lot of people would bat an eye during the head-spinning sequence. But the film is still very gripping.

CA: I agree. First of all, it is a very effective genre film; it builds tension, offers up unexpected surprises, manipulates emotions through its sound design, and establishes an atmosphere of dread from its opening shot, the hazy blood-red sun on the horizon. Although Friedkin denied that The Exorcist was a horror film, he used any number of genre tropes in the film, including jump scares, delayed reaction shots, and even a scene with a woman searching in the dark aided only by candlelight, which even in 1973 was a cliché.

The main premise is also suspenseful. Linda Blair is in spiritual and possibly physical jeopardy, and that scenario—a child endangered—is a plotline made to elicit universal sympathy. Another reason The Exorcist was so powerful was the fact that it was essentially assaultive cinema. Its over-the-top presentation can be considered a strength; in the climactic exorcism scene, for example, the drawn-out ritual is pure overkill, providing a fitting climax for a film that has been obstreperously leading up to the dramatic finale for about an hour. In the last 50 years, some of the effects and dialogue have, to some extent, become unintentionally funny, but, at the time, the intensity of the film was simply overwhelming. It was an exhausting experience for filmgoers of 1973 and 1974.

SN: How would you describe the legacy of The Exorcist today?

CA: Its legacy is as a landmark horror film that revolutionized the genre at the mainstream level. The Exorcist set the stage for spectacle instead of introspection, giving Hollywood the greenlight for other lurid horror films. It is to the credit of Friedkin that none of what arrived in his wake could seriously compete with The Exorcist. Not The Omen [1976], not The Sentinel [1977], not The Manitou [1978], and, although it made a ton of money, certainly not The Amityville Horror [1979], one of the funniest horror films of the 1970s. And the absurd sequels to The Exorcist only served to underscore the power of the original. I think Blatty himself succinctly explained the mass appeal of the film. For more than 20 years Blatty had been dissatisfied with the original cut, and he would often criticize the film publicly. In an interview for a book called Faces of Fear, Blatty gave his own opinion of The Exorcist: “The film of The Exorcist will always remain a phenomenon, but it will never be a classic. It's just a roller-coaster ride—as elegant a roller-coaster as you can find, but that's all it is.”

The Devil Inside: The Dark Legacy of The Exorcist is available wherever books are sold.