Scene Report is an irregular column in which Screen Slate contributors consider a recent cinematic event in retrospect.

“If you make a heterosexual film I can get you more money for it,” New Queer Cinema pioneer Gregg Araki recounts being told by a producer after his “Be Gay Do Crime” micro-budget road movie The Living End (1992), in which two HIV-positive lovers drive towards oblivion, was picketed by outraged lesbians in the Castro upon its release. Ever the punk mischief-maker, Araki took this directive and hit the ground running with the lush and anarchic trojan horse that is The Doom Generation (1995), the second film in his Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy, which opened the NewFest retrospective series “Queering the Canon: Totally Radical” in a 4K restoration of the director’s cut at BAM last week.

“Filmed on location in Hell,'' according to the credits, the film follows the haphazard exploits of three alienated and libidinous teens as they hit the open highway after being implicated in an increasingly surreal array of ultraviolent encounters, experimenting clumsily and sometimes tenderly with non-monogamy along the way. Resolutely committed to the lonesome desert road of the auteur, Araki has made a career of repurposing the industrial scrap metal of cinemas’ past (the ménage à trois of Design For Living, 1933, the deviant interloper of Teorema, 1968) into shiny, infernal contraptions that chug along the blood-stained concrete of his own euphoric junkscape.

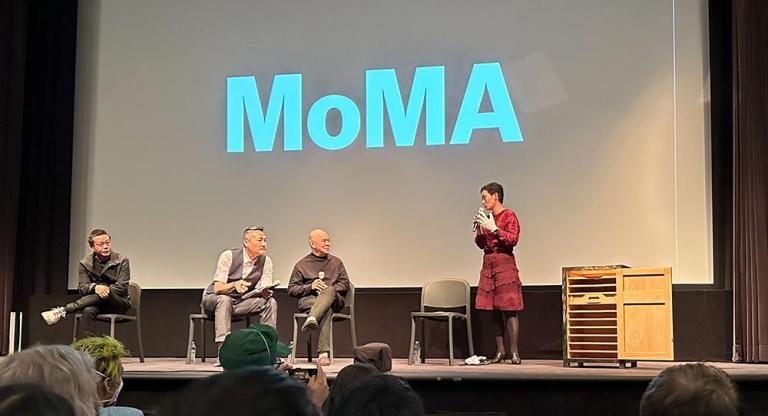

The original theatrical run of The Doom Generation was tragically brief; after its Sundance premiere, it appeared in five cities for less than two weeks, and was then released on home video in a version subjected to numerous unapproved cuts. It has subsequently been available primarily as a shoddy transfer through “some sketchy Russian website,” according to Araki during the post-screening Q&A at BAM, where he, along with star James Duval and director of photography Jim Fealy, regaled the audience with the many trials and tribulations that befell the “cursed” production. Even before reports of disappearing crew members and onset tensions between the talent, the photography from the first day of shooting was destroyed in a lab accident, and the Northridge earthquake struck immediately after. Duval remembered awakening to the ceiling of his hotel room coming down over his head, transformers exploding all around him, and the freeway subsequently flattening on the horizon. Fealy chimed in to confess that the aftershocks of the earthquake are visible in certain frames of the finished film, if you look closely.

This pervasive atmosphere of catastrophe was apropos, given the film’s inclination toward embracing the aesthetics of Armageddon. Araki cultivated a manner of perseverance and crisis management that was spiritually aligned with the puckish can-do attitude of DIY filth elder John Waters. In many ways, The Doom Generation is a coruscating testament to queer resilience, a corrosive indictment of heteronormative values, and an oddly prescient time capsule; the type of lightning in a bottle that could only be generated from the odd frisson of the pop-cultural deathtrap that was mid-’90s Los Angeles. The NewFest Q&A was moderated by Jane Schoenbrun, whose recent narrative feature debut, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021), explores a similar psychic terrain of profound alienation, tonal ambiguity, and teenage anomie, all while addressing the horrors of gender dysphoria for a generation that is terminally online.

“Life is lonely, boring, and dumb.” So goes one of the many enduring adages spoken by Amy Blue, played with sneering detachment and frequent bursts of hormonal vitriol by a young Rose McGowan. (Her shade of lipstick in the film, in accordance with Amy’s taste in music, might as well have been called Cherry-coloured Funk.) When she isn’t hurling baroque expletives at everyone who crosses her path (‘smegma-breath’ and ‘eat my fuck’ being some of the pithier examples), she is subsisting on a diet of Cool Ranch Doritos and crystal meth or fucking her altruistic himbo boyfriend Jordan (James Duval). Matters are immediately complicated when they meet the lupine drifter Xavier (Johnathan Schaech), whose magnetic amorality sets off a bizarre chain of events that includes multiple cases of mistaken identity, satanic numerology, nightmarish cameos, and fits of homoerotic belching.

The crowd at BAM was palpably enthusiastic and receptive to the ensuing calamity. We were an appreciative congregation of intergenerational queerdos, sloppy polycules, Afro-punk princesses, silver foxes in D.A.R.E. shirts, and four precocious preteens whose father figure was the coolest chaperone in attendance. One fan even showed up to greet Araki with a cardboard cutout of the extraterrestrial sodomite from his short-lived Starz series, Now Apocalypse (2019), much to the director’s delight. This screening had the aura of a particularly kinky homecoming dance, and Araki mentioned that the energy was distinctly different from when the restoration was presented at Sundance months prior to an audience largely unfamiliar with the work, to the point where he was momentarily moved to tears onstage by the continued loyalty of his fanbase.

The Doom Generation truly hits different when experienced in a theater full of devoted and gaggling gays, and not accessed from the atrocious pan-and-scan DVD that I stole from Borders while working there as a stoned heteroflexible cashier in high school. The digital transfer restores to opulence the film’s expansive palette of proto–bisexual lighting. It was a thrill to hear the buoyant laughter elicited when Jordan (whose character is part Beaver Cleaver, part Sade’s Justine, and part Bresson’s donkey) confesses that he has a troubled relationship with his parents because “they live in Encino,” and to witness the thunderous applause that occurred when Parker Posey appeared in a loose fitting Brigitte Bardot fright wig, ready to perform a penectomy with a samurai sword.

In a brief intro before the screening, Araki alluded to the explicit content restored in the already divisive finale of the film by joking, “For the people who thought the original ending was a bit milquetoast, now you will get a little more bang for your buck.” Indeed, in the wake of resurgent global fascism and draconian legislation against LGBTQ+ communities across America, the stroboscopic, Dennis Cooper–like brutality of the final sequence takes on new dimensions of urgency and emotional resonance. Is the rectum still a grave? Is life still lonely, boring and dumb?

The Doom Generation is, at the end of its harrowing night, a messy bitch who lives for drama, refreshing in its thematic spillages, its narrative whiplash, and its confrontation of the implicit barbarity imposed by heteronormative structures. It is a timely reintroduction to a legacy of renegade filmmaking, in the midst of a homogenizing wave of sexlessness in contemporary queer cinema, in which the downside of positive representation can often manifest through streaming-service pabulum with thinly veiled assimilationist agendas. In an era where the “No kink at Pride'' discourse flattens creative agency, and the price of gas has effectively punctured the tires of the road movie as we once knew it, The Doom Generation is still reveling in the smell of scorched asphalt, the taste of cum, and the murky politics of desirability.

The Doom Generation: Director’s Cut screens through April 20 at IFC Center.