“The saint’s tooth holds all her good works.” Following this text, we see grainy footage of a gilded reliquary said to contain Mary Magdalene’s tooth—cradled by glass in the form of an egg—in Mary Helena Clark’s Neighboring Animals (2023). The film presents the relic as a surrogate of the saint’s holiness and her body, specifically her mouth: the site of the voice, shaped by the tongue and teeth. In accompanying footage of her laryngeal ultrasonography—a rare self-portrait—Clark repeats the words “hear it” and “worm” as her glottis contracts and releases. The mouth, her collaged text tells us, situates a philosophical distinction between humans and animals. It is also the site of taste and consumption. To these ideas, Clark adds a stream of images—animal dentistry, bite marks, and decorative eggs—for an attentive viewer to find conceptual threads. While watching, I contemplated ingesting Magdalene’s tooth, with all her good works.

Neighboring Animals is installed as a two-channel video in Clark’s solo exhibition at the Bridget Donahue Gallery, accompanied by photographs and sculptures that share her longtime interest in mimesis and the formal instability of such things as mouths, doors, and eggs. Complementing the show, Anthology Film Archives screens the two-part program “Figures Minus Facts: The Films of Mary Helena Clark” this weekend. The first program contains short films made between 2008 and 2020. The second one pairs three of her recent shorts with three films selected by Clark: Michael Snow’s Puccini Conservato (2008), Rosemarie Trockel’s Egg Trying to Get Warm (1994), and Charlotte Prodger’s Passing as a Great Grey Owl (2017).

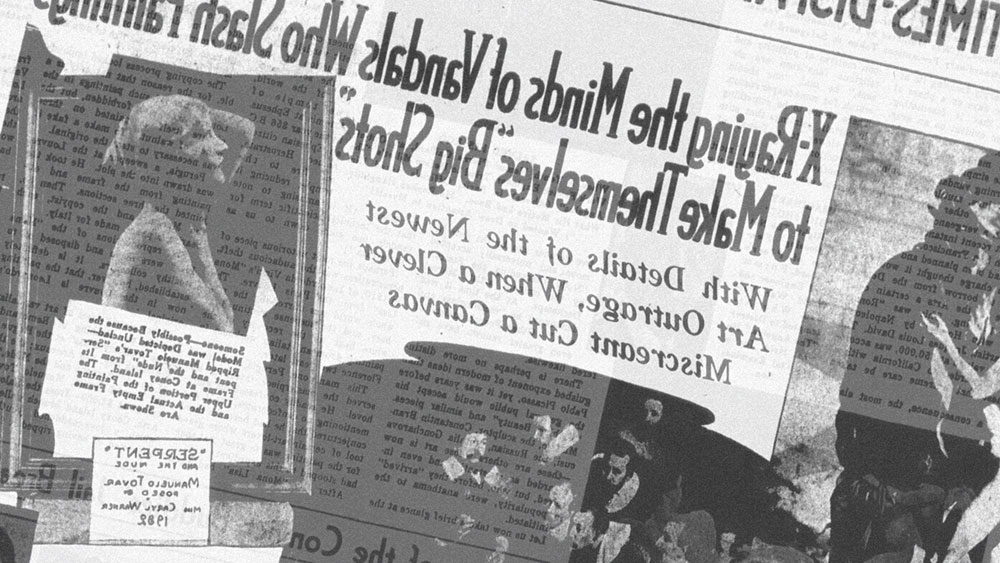

Clark’s films are slippery. This is not frustration; I delight in following her as she traces strange exchanges and dissonances between language, sound, and image. In her films, a door is a wall and an invitation, and a mouth is a vessel and a boundary. In Exhibition (2022), she assembles the following episodes: A Swedish woman marries the Berlin Wall—certificate and all—and, unable to be with her lover, collects miniature models of walls and bridges; the suffragette Mary Richardson attacks Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus with an ax and declares herself a doorknob in her jail cell; and an artist fills a room with klein bottles, functionless objects that physically approximate the mathematical concept of a non-orientable surface. The film’s sound, which features the subtle texture of exhaled air meeting pipes in Eva-Maria Houben’s “Breath for Organ” (2018), corresponds to the blown-glass bottles, each a stand-in for an impossible form. These disparate stories of women’s relationships to objects cohere to show us how desire generates substitutions: a bridge as a spouse, a reclining nude as patriarchy, a woman as a doorknob.

Clark often shoots in 16mm and uses hand-processing techniques to transform concrete images into abstract ones. To make Sound Over Water (2009), she re-photographed and re-processed a single image of a flock of birds; in turn, creating shifting, ambiguous forms. In Orpheus (Outtakes) (2012), she distorts footage from Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950) and other sources through optical printing. At one point, two downturned eyes stare back at the audience from the black screen and a voice asks, “Are you a comedian?” Clark borrowed the audio from a game show and I suspect the eyes are Buster Keaton’s—it’s as if he were in an outtake from Orpheus. Over a sequence of diagonal lines, the sound of the game show’s audience clapping registers as rainfall.

Mourning becomes a state of searching in Clark’s films. The Dragon is the Frame (2014) combines Clark’s 16mm footage of locations from Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)—a retelling of the Orpheus myth—with excerpts from the work of transfemme writer and artist Mark Aguhar. On Youtube, Aguhar (xEmoBoy1987x) posted videos of themselves addressing the camera. In The Dragon is the Frame, Clark shows a clip from Glamour (2012), a video in which Aguhar re-enacts a work by their friend Isaac Pool: “THERE’S SOMETHING ERUPTIVE ABOUT MY PHYSICAL DECORATION, SOMETHING UPSETTING….” Aguhar took their own life in 2012 and their absence is felt in Clark’s melancholic shots of flowering gum trees, empty sidewalks, and shadows. One image of delicate tactility and transience stays with me: A shot of mist giving way to the surface of a sequined curtain where a hand repeatedly smooths the fabric as it fades behind the glass’s reflection of the moving street. Clark called The Dragon is the Frame an “experimental detective film,” a label that befits more of her work. In Figure Minus Fact (2020), made in the fog of another death, the camera attempts to show what is not present. Loss creates uncertain perception, like seeing in the dark. “When someone dies,” Clark wrote in her artist’s statement, “there is a pull towards the concrete and tangible, but disbelief creates a world of unreliable objects.”

“Figures Minus Facts: The Films of Mary Helena Clark” runs February 24-25 at Anthology Film Archives. “Conveyor” is on view through March 23 at Bridget Donahue.