Ang Lee’s Gemini Man (2019) boasts a deceptively simple and (at least, on the surface) intriguing hook: a career assassin is hunted by a mysterious stranger who, it’s revealed, is actually a clone of his younger self. The pitch caught fire in 1990s Hollywood and kicked around development hell until Tom Cruise’s Skydance Media acquired it and brought it to Paramount; Ang Lee and Will Smith were soon attached. Like Lee’s earlier Billy Flynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2016), Gemini Man was shot at 120 frames per second as opposed to 24 frames, the industry standard for over a century. A friend who attended an industry preview screening claimed that Lee introduced Gemini Man with a veiled acknowledgement of the screenplay’s shortcomings, but stressed he couldn’t pass the movie down because it provided him with another opportunity to push filmmaking technology forward. The film failed to solicit audience attention upon release, or recoup its $138 million budget, presumably hurt by the fact it was only available in 3D / 120FPS in 14 theaters nationwide.

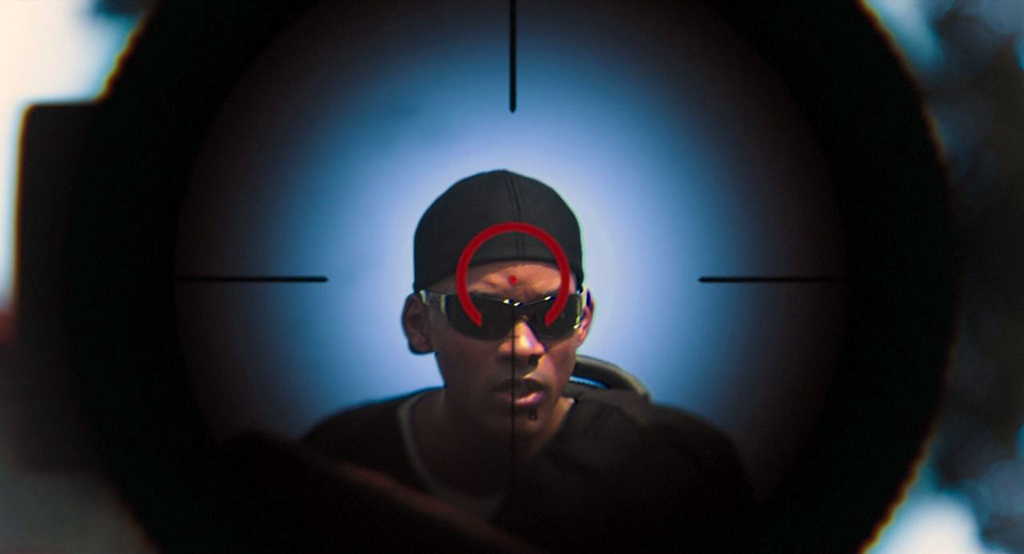

Because I hate myself, I took the initiative of seeing Gemini Man in Lee’s intended format during the one week it was available at AMC Lincoln Square. The movie had an even more crystalline, hyper-fluid quality than most reliably garish and fake-looking mainstream releases of the last decade. It felt a little like watching a video game, an HD-sports livecast, Planet Earth, porn, and a studio film all at the same time. The cumulative 15 or so minutes of action, including a breathtaking motorcycle chase in Cartagena, were almost kinetic enough to justify the film’s unyielding product placement, saccharine color palette, hilariously strained interplay between characters, and belabored plotline.

Taken strictly as a work of cinema and not as a demo reel for obscure and overpriced film technology, Gemini Man is genteel to the point of feeling like self-parody. The totalizing involvement of Smith (one of the last living specimens of the old star-as-auteur model; see also Brad Pitt’s re-editing of James Gray’s Ad Astra, 2019) may be the reason the screenplay is so milquetoast and risk-averse. His character, Henry Brogan, is traumatized and ashamed of spending his adult life carrying off political executions. This has less to do with the policy aims served by his for-hire killings than a certain tug at the heartstrings he feels before pulling the trigger each and every time. Brogan’s attempt to rebuild his life includes a meet-cute with a boat rental manager named Danny (Mary Elizabeth Winstead). While suspecting Danny has been hired to keep tabs on him, Brogan bonds with her by alluding to the difficulty of looking himself in the mirror each morning. At the end of the aforementioned motorcycle set piece, Brogan comes face to face with his assassin, “Junior,” and seeks to find a way to de-escalate the hit placed on him while winning Junior over to his side. It’s not too difficult, as both versions of Henry share confusion over their origins and conflictedness over the mercenary nature of their work. By the final act, they have joined forces to defend themselves against more clones sent by Clay (Clive Owen), the evil defense contractor who reared Henry in the first place.

Gemini Man’s script—an outlier among Lee’s films for having not been written by his longtime collaborator, the great James Schamus—is consistent with many 21st century studio narratives that promise shoot-em-up action without sacrificing facile anti-war political gesturing. Brogan and his friends, other ex-government operatives in varying states of contrition, clink their Stella Artois-es together by saying, “Here’s to the next war—which is no war.” In the post-9/11 era, a mushrooming military-industrial complex has been embraced by both parties as an unfortunate realist necessity. Obama’s push to invert the old stigma of Democrats being “weak on national security” reached its apotheosis in the Harris campaign’s disastrous choice to ignore the Democratic Party base in pursuit of votes from Trump-fatigued Republicans before the last election. To me, Gemini Man typifies warmongering liberal wish-fulfillment, although one sequence deserves mention for interrogating the relationship between shock-and-awe military maneuvering and Hollywood spectacle: Junior eats an ice cream cone distractedly while witnessing a massacre that Lee reveals to be nothing more than an elaborate training exercise.

If nothing else, Gemini Man works great as a portrait of a once-infallible institution hurtling into decline. I don’t believe for a minute that “movies are dead” or “cinema is dying,” but in an era of empty megaplexes and $25 tickets, it seems patently clear that the economic engine of theatrical moviegoing was in trouble well before the Covid-19 shutdowns. Revisited in 2D, half a decade later, Lee’s film testifies to a tangled web of priorities at a crossroads in film history: it’s an auteur’s earnest attempt at making movies exciting again, and yet another ham-handed attempt from Smith to defibrillate a mostly-squandered career (or at least, to add darker shades to his once-beloved wisecracking persona.) The final scene—in which Brogan and Danny drop Junior off for his first day of college—is perhaps the most awkward happy ending I’ve seen in a studio film this century. Lee’s film is special because—to quote Raoul Duke’s send-off in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Self-Loathing in Las Vegas—it was always too weird to live, yet remains too rare to die.

Gemini Man screens this morning, February 23, at Asia Society as part of the series “Water and Oil: The Movies of Ang Lee.”