When I was a teenage cinephile, my father pitched me Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925) as a home movie. The Baba Ahmadi tribe depicted on screen was his own, and my grandfather was an infant when Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack filmed the tribe’s semiannual migration from southwest to central Iran. It’s a rare privilege to have one’s family inscribed in celluloid for subsequent generations. Such a record is always incomplete and palimpsestic, effaced by whomever is wielding the camera.

Cooper and Schoedsack are briefly established at the film’s outset as the men documenting the reporter Marguerite Harrison’s trek from Turkey to the Khuzestan province of Iran in search of “the Forgotten People.” All three are white Americans. The Orientalist tone of the film is compounded by cloying colloquial comedy in its early passages, including an Anatolian magician’s repeated use of the word “feller” in Paramount-supplied intertitles. Despite their purported reverence for the resilience of their subjects, the filmmakers constrain themselves to a patronizing, atavistic lens.

In a rare nod to geopolitical intrigue, the closing reference to the murder of Robert Imbrie in Tehran is an inadvertent portent of Reza Khan’s seizure of power later that year, marking the dawn of the Pahlavi Dynasty. Yet Cooper and Schoedsack’s evocation of a mythic past remains wholly disinterested in the nation’s future. Instead, the Baba Ahmadi’s journey across the Karun River and over the Zard Kuh mountain range allegorizes a Western mythos of man’s superiority to nature. Schoedsack’s photography is particularly effective at dramatizing this dynamic in wide shots of 50,000 people hiking up the Zard Kuh in a zigzag formation.

Grass’s legacy is twofold: it has held an affirmative significance for Iranians, at least since its revival at the Shiraz Arts Festivals in 1976, while enforcing a Western ideological hegemony. The tribe leader, Haidar Khan, and his nine-year-old scion, Lufta, are distinguished from their fellow Bakhtiari yet remain archetypes upon which viewers are invited to project their own biases. Looking at father and son, I too unavoidably consider my own paternal lineage refracted onscreen. That strangely poignant interplay between recognition and othering makes Grass an indelible cinematic Rorschach test. Bound within the history of the cinematic medium, I reclaim vestigial traces of my own family history.

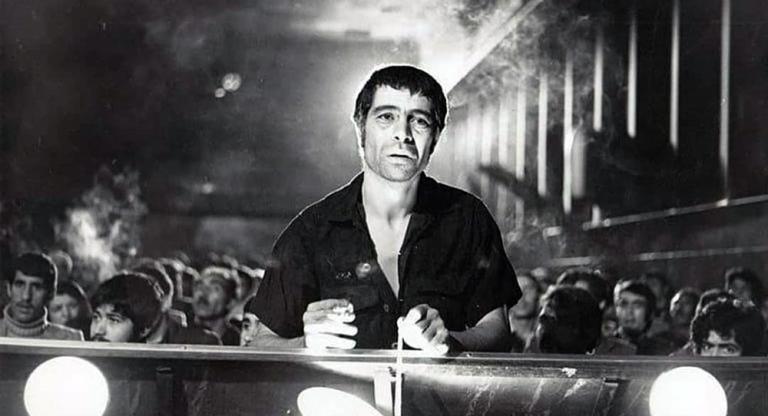

Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life screens this afternoon, November 18, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of the series “Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, 1925–1979.”