For how long after someone you love dies can you touch them and still feel them touching you back? Early in David Cronenberg’s new film The Shrouds, innovator Karsh (Vincent Cassel) explicates Jewish ideas around death as his late, beloved, Jewish wife Becca would have understood it: after the body dies, the soul departs slowly, unable at first to totally separate from the physical form it had inhabited, hovering around it for a while before, gradually, dissipating, like wisps of clouds pierced by the sun and scattered by the wind.

This is a very Cronenbergian sentiment: “Body Is Reality,” and the corporeal form is not the vessel for personhood, it is personhood—nevertheless, something lingers, ghostly, even if only imprints in the neurons of those left behind. As a metaphor for the grieving process, it’s hard to top GraveTech CEO Karsh’s innovation, the Shroud: an eerie, textured black burial shroud, halfway between Hefty bag and cocoon, equipped with miniature HD cameras, providing a live 8K feed, accessible on an app, of your dearly departed’s deteriorating corpse—a body in the ground and a soul, as it were, in the Cloud.

This is “posthuman” in multiple senses: death and remembrance as an organic process now mediated through screens, which leads to an uncertainty over memory that is also part of grief. Karsh is “locked out” of the app, and Becca’s grave—as indeed we all are—after an act of cemetery vandalism that could be the work of Chinese spies, Russian hackers, or Icelandic eco-terrorists, all possibly eager to weaponize the Shroud’s technology, or disrupt Gravetech’s plans for global expansion. Just what are those nodules on the archival video of Becca’s bones—tumors her doctors missed, or experimental surveillance devices they secretly implanted? Karsh delves deep into an impenetrable, DeLilloan plot, at once vague and prescient, with the aid of his irritable IT guy Maury (Guy Pearce), who scarfs down pastrami sandwiches and matzoh-ball soup in between wheedling at Karsh for news of his ex-wife, Becca’s twin sister Terri (Diane Kruger), at once the Midge and the Judy in the film’s Vertigo-like matrix of nostalgia and desire. Kruger also plays Becca in powerful, tender and disturbing flashback scenes, depicting her and Karsh’s undimmed hunger for each other despite her body’s deterioration from a wasting illness. (Cronenberg’s wife of 38 years, Carolyn Zeifman, died in 2017, and the filmmaker has been open about The Shrouds’ autobiographical inspiration.) But Karsh’s memories of Becca are also contorted by paranoia, as his conspiratorial speculations about her death and the destruction of her grave begin to encompass theories about her relationship with her doctor; and he has begun to spend time with Soo-min (Sandrine Holt), the wife of a Hungarian business partner, who might take his “neo-virginity” as the memory of Becca changes and fades along with her body.

The work of a master utterly confident in his methods—the well-grooved dialogue, the icy cinematography by Douglas Koch, the eerie music by Howard Shore—and curious about new frontiers of experience, The Shrouds is also utterly at home in its own beguiling eccentricities. Midge works as a dog groomer and the visually-impaired Soo-min uses a seeing-eye dog, so the presence of companion animals adds an earthy texture to many high-stakes discussions of grief and death; Karsh lives in a Japanese-style condo complete with a koi pond, a nice joke about the ostentatious, spiritually-inclined minimalism of the tech CEO lifestyle, echoed in a late, funny insert close-up of his blindingly white executive-suite sneakers clomping through the mud. And no discussion of the film would be complete without mention of Hunny (voiced by Kruger), Karsh’s AI assistant, who takes on many forms, all of which illuminate our emotional dependence on disembodied technology, for better or worse.

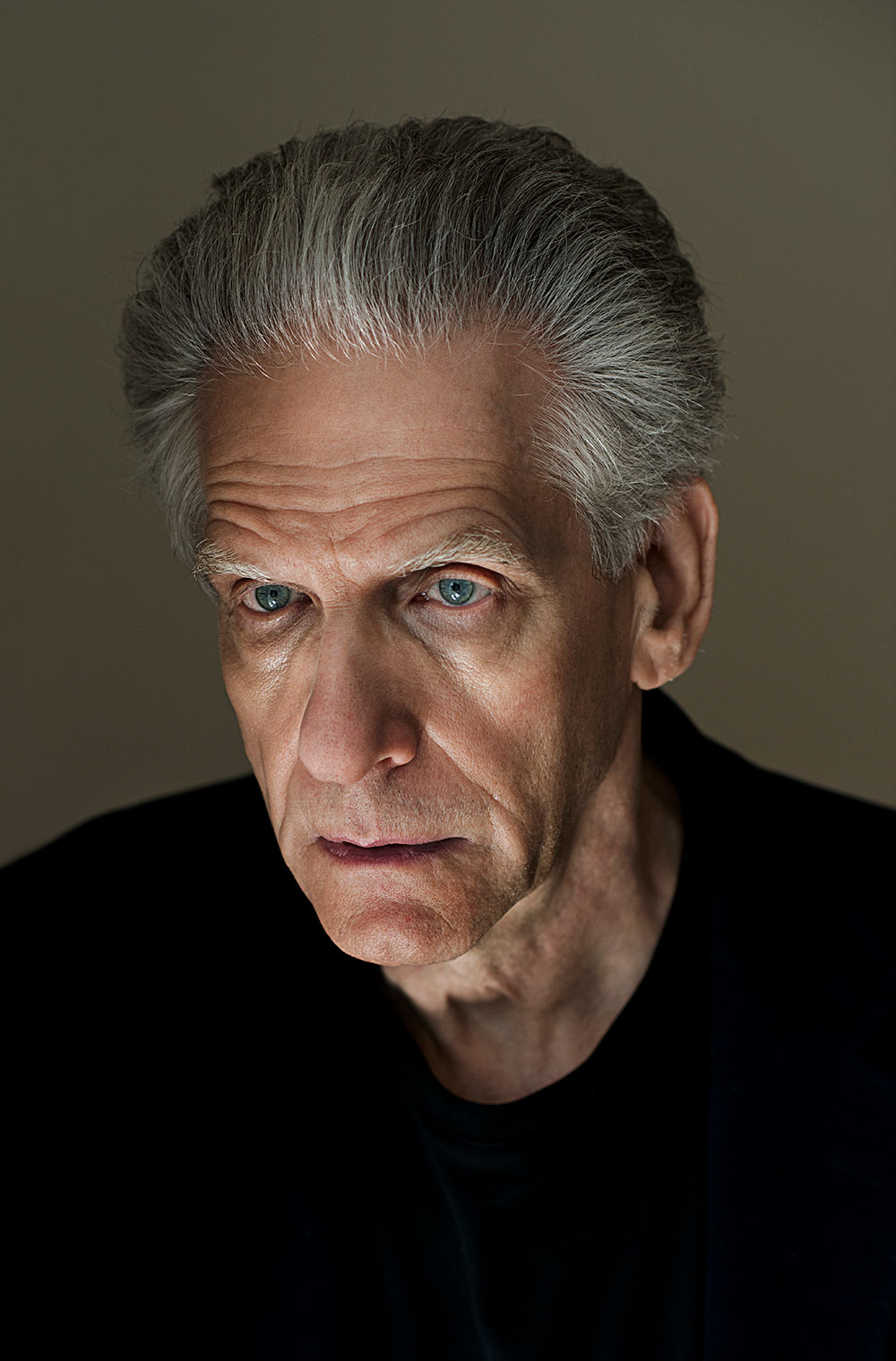

Witty, avuncular, and generous with his intellect, Cronenberg is a joy to interview. I had the privilege of speaking to him last week when he was in town for The Shrouds’ New York theatrical premiere.

Mark Asch: When this film premiered at Cannes last year, I went around to my friends and colleagues, taking a poll, asking them if they could see themselves using the Shroud. Obviously it’s a very strong metaphor, but I’m curious if you have encountered people who have a strong reaction to it as a product, in either direction.

David Cronenberg: Well, I’ve tried to get people to tell me. Mostly they ask me if I would have done that, and my answer is yes. I have to assume that however strange I might or might not be, I cannot be alone in this world of billions of people. And also, when you consider the strangeness of some burial practices around the world—I won’t get into which ones, but I did a lot of research when I was thinking about this movie—I have a feeling that there would be a clientele who would be interested in doing this.

MA: I can tell you that I got 14 nos, 11 yeses, and one “Oh jeez, I don’t know.” And I had two people ask if they could use it on an enemy.

DC: That's a nice one.

MA: I remember thinking that I would use the Shroud. I wouldn’t want her to be alone down there. I also think that at a certain point it would stop resembling the person I missed, and I could move on because there wasn’t a her I was separated from.

DC: But you don’t know that that would be your reaction. You’re anticipating that it might be, but maybe it would continue. Maybe there would still be a connection. Anyway, who knows, I can imagine all of those possibilities for different people.

MA: To continue with gravesites, the inciting incident in the film is an act of cemetery vandalism, which, because Becca was Jewish, made me think of how the desecration of a gravestone is a hate crime in general—Black cemeteries are vandalized in the same way Jewish cemeteries are, et cetera—but also a classic manifestation of antisemitism.

DC: I wasn’t making a big deal out of it, but it was there to be seen and understood. Grave vandalism usually has a larger context around it, and so although, in this case—we don’t want to spoil the movie for people, but—there was a specific vandal involved in this crime, I knew there would be resonances. And of course, I do cut to the Star of David and Hebrew letters and so on on the gravestone, so you know that that specifically was a Jew buried there, in the grave that was vandalized.

MA: It’s an attack on memory as well, a denial or rewriting of this plot that you’ve buried somebody in, but also the plot that you’ve written by creating this memorial to them. But there’s also a paradox with the vandalism of a Jewish grave. When I was in Hebrew school, as I was in the years leading up to my Bar Mitzvah, the subject of what happens to us when we die just never came up.

DC: Really? That's shocking.

MA: If we did, I don’t remember. But a huge motivation within religion…

DC: Christopher Hitchens said, “Death causes religion.”

MA: The Shrouds is a kind of thriller about grief, in which the memory of Becca supersedes the lived experience of her, and tension and uncertainty arises because Karsh’s memory of her is in some way compromised or contested. How do flashbacks function in the film? Is his memory totally reliable, or, in your mind, is there something in flux?

DC: I deliberately wanted to avoid the traditional use of flashbacks—the flashback to when they first met, the flashback to when they went on that great vacation in Switzerland, the flashback to when they had that fabulous birthday party—because Karsh is forced to focus on the hideousness of her death and the pain of her death. You really just see Becca in her agony, rather than when she was in great shape and they were lovers and it was all terrific. I felt that that was, from his point of view, at this particular moment in his life, not really a flashback. It is sort of a curated memory, let’s say, and it’s kind of a nightmare. He’s remembering her when she was in agony. I think anybody who’s had somebody who’s been really sick probably has had some dreams like that. It’s not really a hard and fast flashback, which could be accurate or not accurate, but more like a nightmarish version of reality.

MA: This leads to maybe another question about corporeal versus disembodied essence. The surgery sequences in Crimes of the Future [2022] were a combination of practical and digital effects. What is the balance here?

DC: It’s a combination. I think of AI and digital effects as just being another tool in the toolbox. To me, it’s not a political thing, it just gives me much more flexibility to do all kinds of things, and I don't really worry about how real it is. Film is illusion. You’re not making a documentary. Even if you are, you are creating a universe that lives on its own. So, I used whatever was available to get the effect I wanted. And yes, there was a lot of physical prosthetic stuff that Diane had to endure, but that was also combined with amputations that were obviously digital.

It’s so much easier now. It wasn’t that long ago that you’d have the actor wearing a green-screen sleeve, for example, so that they could remove that part, separate it from the frame. Now, they don’t even worry about it. You can track any part of the body you want. It’s very sophisticated and very easy to do these effects. It’s not like Marvel Universe kind of stuff, where you’re... marveling at what you’re seeing. This is meant to feel real, even though, basically, it’s a dream sequence. But it’s a dream sequence about what has really happened to the character. So I welcome it. I don’t think there’s any innate value, superior value in physical effects as opposed to digital effects. It’s all a question of how real does it seem or not? That’s the bottom line.

MA: In this film, there’s a number of layers of reality, whether it’s through the scrim of memory, as in the flashbacks, or whether it’s looking at an iPad and videos that may or may not have been doctored and edited. I don’t know whether you would compare them to deepfakes, or what. So there is a sense in which, because we’re perceiving these things at a remove from our senses, they are more untrustworthy.

DC: Someone pointed out the possibility that the images of his wife’s decomposing body are also not real, and that there is no body there.

MA: Well…

DC: There you go. That is a legitimate supposition.

MA: In a practical sense, how do you find directing or supervising digital effects work? Is it different? Has there been a learning curve in the time that that’s become more prominent in your practice?

DC: It’s been huge, but it’s been gradual, and I just absorb it happily. Now, for example, you have a digital sort of overlord on set. Not an overlord, but a guy who’s there to make sure, if he has to take high resolution stills of something, that it can be fed into the CGI mill. He’s the liaison I have with the effects people. In this case, the main effects group was French, and they did really beautiful work. It’s different, but similar, because with prosthetics, when I was working with Rick Baker, it’s collaborative. You would have a discussion. He would show you things. You decide how that works. In terms of collaboration, it’s not different. It’s not really different than working with the cinematographer, actually.

I know that for fans who are interested and obsessed with this and with AI and stuff, it might seem like a big deal—and it is a big deal, in terms of how much flexibility you have. Also, it’s cheaper. As the technology becomes more available, it becomes cheaper to do these kinds of effects. But then you still have to have the vision, and it has to mean something.

With the Adrien Brody thing, there was a question of, is this legitimate? Is he not an actor, because the AI was used to correct his Hungarian accent? We’ve been manipulating actors’ voices forever. I’ve done it way in the past, with M. Butterfly [1993]. I raised the pitch of John Lone’s voice when he was being a woman and then, when he was being a man, lowered it. Nobody thought about it twice. This is just a more sophisticated version of that. We are not making a documentary. It's not like you’re saying, “This is what really happened, and ‘I'm not manipulating it.’” Filmmaking is manipulation. I don’t see it as being less real, less valuable, less credible, less honest. You are creating a phantom.

MA: Who designed Hunny? Was it the French firm?

DC: Actually, we put Diane Kruger in a motion control outfit, and she acted Hunny the way that you normally do whenever you’re doing motion capture. You have, like, 14 cameras around her and she's doing all this stuff in the middle of a big warehouse. And then you can do what you want with it. She could have been a rabbit. That was done in Toronto.

MA: And the animation style…

DC: I didn’t want it to be Uncanny Valley, which I could have done, but I felt that Karsh wanted an avatar that looked somewhat like his dead wife, but wasn’t looking for an AI perfect version of her. So it was his decision to make her more like a cartoon version.

MA: The collaborator on this film that you’ve worked with the longest is Howard Shore—when does he become involved in the process? Are you talking with him while you're writing? Do you show him a script, rushes, a cut?

DC: I was just in London where the London Soundtrack Festival did a weeklong homage to Howard. I was there doing Q&As with him, talking about exactly this kind of thing. It was really sweet. They had the London Philharmonic playing live to the picture.

There are several people I tend to send a script to early. One would be the cinematographer, one would be the editor, one to Howard, and one would be to Carol Spier, my production designer. I send him the script at a very early stage, and he starts thinking about what the movie might be and what the music might be. Eventually, I send him a first cut of the movie so that he can feel it. In the past, he's often come to the set to get a good feel for what’s going on. We are constantly talking about it—but we don’t talk a lot.

It’s very difficult to talk about music, so it’s a kind of a telepathy. I think we've done 17 films together, and we both come from Toronto. We come from the same place, culturally. When the film gets closer and closer to being fine cut, we have a screening together, and we do a spotting session, which simply means that we say, “Okay, does this scene [need music]? What about music here? Do we have music here, or do we not?”

We have a feeling about music, which is that music often, most often, is used just to accentuate what’s already there. You have a scary scene, you have scary music. You have a romantic scene, you have romantic music. We think that’s a missed opportunity, because the music can be another character, can allude to a different thing other than just what’s obviously there. Sometimes I think music is there because of insecurity. You’re worried that it’s not impactful enough, so you want music to accentuate that. You see that in streaming series now, there’s a pounding all the time. Even when people are just walking down the street or driving a car, just to give it dynamism and meaning and whatever. We do a different thing, but that’s hard to talk about. I can tell you what I think is happening with Howard’s music.

MA: What do you think is happening with Howard’s music?

DC: The way I wrote Karsh and the way Vincent plays him, he is very controlled. He’s distanced enough from his wife’s death that he is able to be humorous about it. He’s able to be very cool about it. He’s not sobbing his guts out constantly. But the music is saying that underneath that is… agony. Is disaster, is depression, is intolerable sadness and melancholy. That’s the other part of Karsh. That’s the part that the actor is not giving you directly—except for a couple of scenes.

I have a lot of dialog in my movies, and dialog is very important to me. I don’t think of film as being just a visual medium at all, and for there to be music over a dialog scene is a big deal for me. It’s interesting because it contrasts with Peter Jackson, who in his Lord of the Rings has [Howard Shore’s] music over everything. That works for him. He has it over dialog. It’s not the way I want to use music.

MA: How did the Iceland scenes come about? With Ingvar Sigurðsson talking to Karsh on the FaceTime call that keeps dropping out. What was the motivation for writing Iceland into the film, and also for dramatizing the scene that way?

DC: Originally, I was thinking of this as a Netflix series, and I was going to have there be a different country every week in which Karsh would try to set up one of his cemeteries. And in each case, he would run into politics, religion, economics. It could be quite fascinating, because every country has a different version of all of that stuff.

A lot of people are fascinated with Iceland, because of the landscape and so on, being so unique and intense. I thought it would be interesting for him to think that maybe he could set up a version of his high tech cemeteries in Iceland. And then when, finally, Netflix decided they didn’t want to do the series, and I decided that I still wanted to make a movie out of it, I still liked the Iceland element. Although he doesn’t go to Iceland, he goes to Iceland virtually. I have a friend in Iceland who connected me with that actor. I didn’t travel there, I directed it virtually. I was watching as they were recording it. It was an interesting experiment, because I hadn’t really done that before.

MA: Sometimes in The Shrouds, scenes play out on a close-up of a hand holding a smartphone which is playing a video, which is a fascinating way to to stage and to show action.

DC: I thought that if Karsh was moving ahead with his idea of cemeteries in Iceland, he would start to probe at a distance. The other time is when Diane Kruger was actually shooting [a scene with Guy Pearce]. It was also handheld iPhone shooting for a very different reason. In each case, the actor was actually shooting it.

MA: We know, as Karsh explains, that the body decomposes, the soul disappears, floats up and becomes disembodied. But we also still feel it’s significant that the grave is vandalized.

This leads me to an eccentric question, if you’ll bear with me. Where I grew up there was this cemetery that had fallen into disrepair. There was grass growing, the graves weren’t maintained. It was near my high school, so we would have baseball practice there. You just had to avoid tripping over the headstones. But the big thing was that it was used as a dog run, and people would take their dogs off leash there, which eventually became a huge controversy, because even though it wasn’t the descendents of the people buried there, people had the idea that it was disrespectful to have dogs lifting their legs on headstones. Having seen The Shrouds, I wonder how you feel about that—the idea of people jogging in cemeteries, taking their dogs to run around in cemeteries.

DC: There’s a huge cemetery in Toronto, Mount Pleasant, that’s constantly used by runners. I don’t think dogs are allowed, but runners do run there, and it’s meant to be a way of integrating a cemetery into a community and saying, “This is a normal place to be.”

You don’t have to think of it as a sacred place in religious terms, but is it disrespectful [to have dogs urinating on the gravestones]? People who are related to the people who are buried there would obviously find it disrespectful. But in Mount Pleasant, they don’t find it disrespectful that people are jogging through there, meeting their lovers there and whatever. It’s a park. And I think that’s about the right balance.

MA: I remember being a teenager and thinking that if someday a dog is lifting its leg on my headstone, then I’ve been useful, I’ve maintained a connection to the natural and necessary physical world.

DC: Well, homeowners hate it when dogs do that to their trees. It’s not necessarily a matter of disrespect to the dead. It’s just, curb your dog. But I don’t disagree with you. Your version would just be extending the idea of a graveyard as part of a community, rather than [being] weirdly isolated, hidden perhaps.

The Shrouds is now showing in select theaters in New York and Los Angeles and expands nationwide Thursday, April 24.