A sci-fi film set in the dreary present, a romantic-comedy about two people that never meet, an Antonioni-esque look at urban squalor, and a jukebox musical, Tsai Ming-Liang’s The Hole (1998) is as protean as it is potent. Ostensibly a story of two neighbors who start interfering into each other’s lives through a hole in their shared floor/ceiling, The Hole carries all the allegorical clarity of a tale by Kafka or Poe in its revelations about modern urban living and alienation. Like in many Tsai films, dialogue and plot are deployed sparingly in favor of delicately composed poetic imagery, lengthy depictions of ordinary behaviors, and a parade of cryptic, comically absurd vignettes.

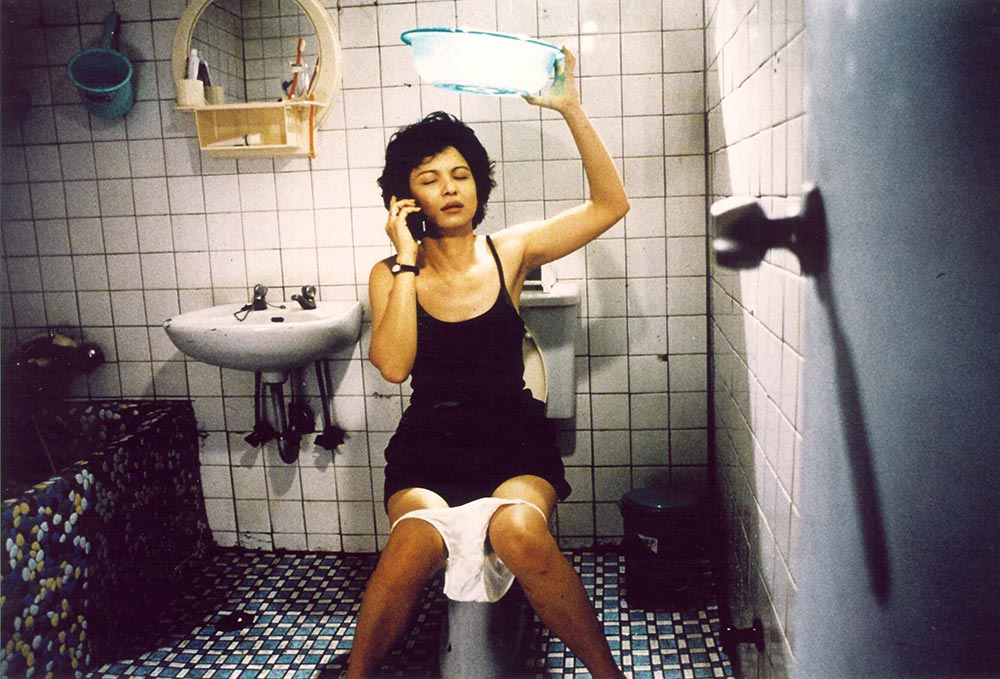

Set in the year 2000, The Hole depicts a Taipei devastated by something known only as the “Taiwan Virus” which induces cockroach-like behavior in those it infects. Quarantined inside their apartments, Hsiao Kang (Lee Kang-sheng) and his unnamed downstairs neighbor (Yang Kuei-mei) live closed-off and isolated lives that, virus or no virus, might as well be described as insect-like themselves in their dreary monotony and surrounding grime. Besides the petty annoyances and secret romantic longings they feel toward one another once the titular hole starts disrupting their lives, there’s little more for them than eating, sleeping, going to the bathroom, and watching TV news.

For all its conceptual inventiveness however, The Hole is not a film concerned with pat ironies or even overt thematic messaging—Tsai is too observational to ever concern himself with making a point directly. Instead the director digs into the spiritual impoverishment of the modern world through a patient and measured film language. Through minutes-long shots of characters sleeping or walking through vacant marketplaces, Tsai’s imposed austerity generates a palpable sense of melancholy and longing. By the time something like a spiritual awakening comes, granting the characters their sorely needed emotional connection, it carries all the rapturous sublimity that comes in the leap-of-faith resurrection in Dreyer’s Ordet (1955) or even Spielberg’s E.T. (1982).

Yet to call The Hole durational would be to do it a disservice, conjuring an idea of a patience-wearing slowness that neglects how elated and spontaneously fun it can be. Tsai’s first musical, the film uses the songs of 1950’s Hong Kong pop star Grace Chang in vibrant song-and-dance routines that adapt the emotional and generic logic of the Hollywood musical with an art-house fixation on proletarian reality. The numbers begin suddenly and unexpectedly, taking unstated emotions and launching into wild reveries of romantic engagement.

These numbers both compound and dispel the characters’ sense of detachment, giving vent to buried emotions but keeping them buried inside a pop-fantasy that exists parallel to their lives. This gets close to the heart of moviegoing itself, in which we seek out fantasy to compensate for a lackluster reality, though we often find ourselves alienated by these very escape mechanisms. The alienation of the moviegoer would become its own overt theme in Tsai’s subsequent films; in The Hole, it is enough to enfold our own complicated experiences as spectators into its worldview. In accommodating both our fantasies and our disappointments, the film evinces a belief in genuine human connection in a world where it seems all but impossible.