Tomorrow, November 18, marks the 30th anniversary of the performance that was subsequently broadcast and posthumously packaged as Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged in New York. Anyone who has so much as typed “Nir–” into a search engine this calendar year was probably inundated with promotional material regarding the 30th anniversary reissue of the band’s final studio album, In Utero, last September. We have about four months until the 30th anniversary of Cobain’s suicide, but before that we can enjoy the 30th anniversary of his 27th birthday on February 20. Nevermind turns 33 next September. We’re only nine years shy of Bleach’s 43rd. Mark your calendars.

Sneering at harmless numerological fun in a miserly world feels like an unforgivably grinchy pose, but the bar has fallen hopelessly low for the sort of commemorative cultural nostalgia cooked up by web editors and record labels who can’t believe their good fortunate that round numbers are sufficient reason for the public to buy the same shit again and again. Writing about Cobain for Rolling Stone’s dubious “Artist of the Decade” issue in 1999, Greil Marcus quoted Kurt fave Flipper’s encapsulation of the 10-year memorial cycle: “Life is pretty cheap / It’s sold a decade at a time.” The tendency has far more to do with the ouroboros of mass media spectacle than with any sober reflection on time’s passage and the lessons learned.

Numbers—anniversaries, album sales, t-shirts SKUs, tickets, licensing figures, TV ratings, copycat suicides—have their place in the analysis of any cultural happening, but mostly they’re deployed as escape hatches for people eager to weigh in without having anything to say. Reiterating how much is quicker work than describing how, which requires some personal risk from a commentator tasked with sifting through collective experience in search of illumination. Big numbers feel objectively meaningful until you get around to considering the chart history of something like “Dance Monkey.” It’s not uninteresting that a punk band sold more records than Celine Dion (though far fewer than Shania Twain). But if that’s the crux of this story, we’ve lost the thread of what continues to draw us to this music and its surrounding dramas thirty years later.

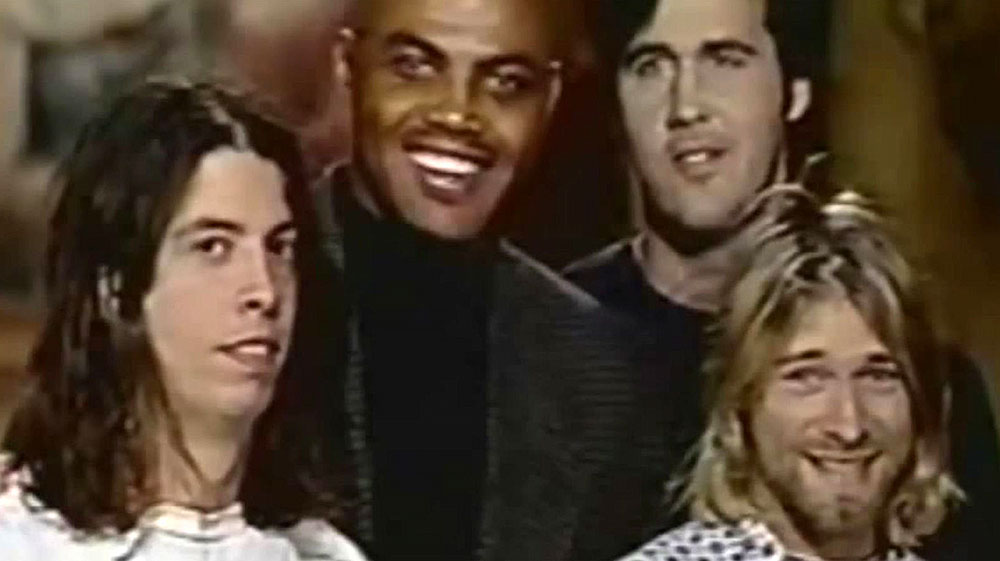

The how of Nirvana and Cobain is beautifully captured in Greg Eggebeen and Benjamin Shapiro’s illicit archival documentary I Hate Myself and I Want to Die (2012–2023). Pulling from contemporary news broadcasts, live performances, Guitar Hero clips, interviews, home videos, and Unsolved Mysteries segments, the duo let the risible, backfooted feeding frenzy of mass culture speak for itself in largely interrupted blocks of anti-soundbites. What’s so refreshing for anyone who’s tried to digest the band’s story previously is the wealth of context on display. This is the closest any document has yet come to capturing how it all happened, which is to say how the media event that was Nirvana unfolded before the public: with Michael Richards in full Kramer getup announcing another VMA victory, with the band competing alongside British electronic duo Altern 8 for chart dominance, with an Australian muppet sullenly nodding alongside his human cohost while getting the news that Cobain was dead, with Robert Stack gravely considering Kurt-was-murdered conspiracies, and with the band playing music that was brilliant and life-affirming.

I Hate Myself and I Want to Die screens at Spectacle tonight, the premiere of a new version of the film.