For the first fifteen-odd minutes of Ashish Avikunthak's Katho Upanishad (2011), the camera sneakily tracks a man navigating a mysterious forest in search of someone or something. Not a word is uttered, and the only sound is the ambience of myriad buzzing species. The almost one-hour-long second act is again a single shot that sees Avikunthak imaginatively adapting the eponymous 2,500-year-old Sanskrit treatise, in which Yama, the god of death, instructs the man, Nachiketa, about the path towards enlightenment. This indulgence in long takes accentuates the temporality and spatiality of Avikunthak’s film.

In a twenty-five-year long career, the maverick film artist (who doesn't like being called a filmmaker) has been operating in a silo, far away from the mainstream marketplace and separate even from the fringe of parallel cinema in India. Avikunthak’s stylized experimentation with form, combined with abstract narratives, render his films challenging to even most experimental cinema lovers, leaving very few takers for his truly unique idiom. Until this year, Avikunthak's films could be accessed legally mostly through screenings at film festivals, museums, and art galleries. Now, eleven of his films are streaming on MUBI in a retrospective titled An Idiom Unto Itself.

Engagement, and not comprehension, is what Avikunthak primarily seeks from his audience. A provocation accompanies this retrospective: “The answer to the riddle is not important. The riddle itself is the answer. The mystery itself is the code. Is it possible to look at my films in this way?” While this might be the most effective way to engage with his radical short films, his features are fairly easy on the eye and the mind.

Where the aforementioned Katho Upanishad evokes mysticism and tranquility through the terse philosophical discourse between Nachiketa and Yama, the verbose Rati Chakravyuh (2013) creates an atmosphere of dread as six newlywed couples and a priestess sit in a circle discussing life, death, and the politics of violence. Avikunthak and his cinematographer Basab Mullick (who also filmed Katho Upanishad) used a circular dolly to revolve around the characters throughout the film's 102-minute runtime, creating a spiral effect and another unbroken shot. Even his debut feature, Shadows Formless (2007), features a daring formal experiment. Avikunthak interprets, in Bengali, the Malayalam-language novella Pandavapuram (1995), by Sethu, to critique structural violence against women. Here, the unreliable narration echoes the whimsical frames, which change between black and white, sepia, and polychrome, even within the same sequence.

Avikunthak's motifs of religiosity, mythology, and philosophy, and the socio-political undercurrents that pervade his oeuvre, amalgamate yet again in his fourth feature, The Churning of Kalki (2015). Inspired by Samuel Beckett's existentialist play, Waiting for Godot (1953), the film follows two men who arrive at the Maha Kumbh of Allahabad—the largest congregation of humans in the world, which occurs once every twelve years—in search of Kalki, the tenth and final avatar of Lord Vishnu. Unlike in their previous two feature films together, Avikunthak and Basab play around quite a bit with cinematography in this one, getting away from their long takes. Not only do the visuals toggle between grayscale and color, but even the medium varies between 16mm (daylight shots) and digital (night shots). The synthesis of grainy, high-ASA stock and crisp digital images appears seamless as the granular texture permeates almost every frame to lend the film a uniform look, an effect that took Avikunthak a lot of time to create in post-production.

To witness Avikunthak at his rebellious best, one needs to watch his early short films. They exploit the possibilities of cinematography and editing to create complex visuals, interspersing slow and fast motion, step-printing, motion blur, and circular shots. Avikunthak toys with exposure as and when he pleases, especially in End Note (2005), where he brazenly intercuts between underexposed and overexposed images. In Avikunthak’s wildly imaginative world, hybridization isn't just restricted to cinematic form but also to the art of his collaborators. The 2002 short Dancing Othello sees the auteur capturing the inventive performance of Arjun Raina—an artist who fuses the Indian classical dance form of Kathakali with Shakespearean drama.

Preferring to shoot on analog over digital, Avikunthak is fascinated with retaining grain, noise, and scratches in the finished images. The archaic look of his shorts corresponds well with their thematic reminiscence of the past, be it a contemplation of India's colonial history through a dilapidated crematorium in Performing Death (2001), an age-old religious tradition in Kalighat Fetish (1999), or the juxtaposition of an archaeological excavation with amateur 8mm found footage in Rummaging for Pasts (2001). These films interweave shots of commoners at beaches, flea markets, and festivals, connecting the present with the remnants of the past. Correspondingly, the soundscape combines ancient mantras, hypnotic music, and the rawness of ambient noise.

The two shorts that stand out in Avikunthak's filmography are the ones that indulge heavily in his preoccupation with life, death, and beyond (if at all there is!). His debut, El Cetera (1997), is a tetralogy of four separate films made between 1995 and 1997. They seek to examine the various levels at which human existence functions and whether or not it can be transcended. Through the four films—renunciation, soliloquy, circumcision, and the walk—Avikunthak hints at a total surrender of the self and the soul’s subsequent liberation.

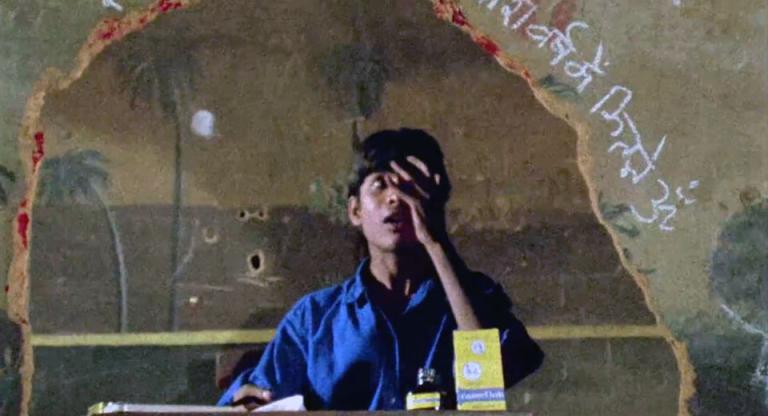

In 1997, Avikunthak also filmed a sequence of a friend immersing an idol of Lord Ganesha at a beach on the last day of the Ganapati festival. A year later, that friend committed suicide. Over the next twelve years, Avikunthak shaved his head off three times and shot an inventive collage as a requiem to his friend. This poignant short, Vakratunda Swaha (2010, pictured at top), seeks to question the meaning of existence and the possibility of freeing oneself from the cycle of life and death.

In the Hindu religion, getting one's head shaved after the death of a loved one symbolizes the dissolution of the ego, marking the beginning of a new consciousness that is pristine and non-divisive. Vakratunda Swaha explores the notion of rebirth and the fluidity of identity as the two protagonists (one played by Avikunthak himself) engage in role-reversals. Avikunthak also scrutinizes the significance of God in our modernized world, where sinister-looking gas masks with long pipes resemble the elephant face of Lord Ganesha. In this deeply personal film, using old unexposed film stock procured from eBay and a vintage French 16mm camera which could shoot in reverse, Avikunthak delves into the tragedy of bereavement and the magical reconstruction of the past.

The similar climactic scenes of Vakratunda Swaha and Katho Upanishad might offer a sense of Avikunthak’s mystical aspirations. The protagonists in both films are seen walking in the middle of a highway toward the camera, whereas the vehicles on both lanes are mysteriously moving in the reverse direction. Is the viewer supposed to infer from this bizarre act the individual's transcendence of the illusory material world onto the path of enlightenment? I think Ashish Avikunthak would prefer this mystery to remain unsolved.

“An Idiom Unto Itself: An Ashish Avikunthak Retrospective” is now streaming on MUBI.