Despite 25 years of dismissal and mockery, Johnny Mnemonic remains a visionary forecast of the networked society. No pre-millennium Hollywood production captured the anxieties and exhaustion of living online so well, despite studio butchery that deprived audiences of writer William Gibson and director Robert Longo’s ambitious vision. Now Longo triumphantly returns to the film that began and ended his career in Hollywood by unveiling a black-and-white version that effectively defaces the original release’s expensive veneer. Without altering a line of dialogue or shot sequence, Longo reconfigures the tone of the film, dialing up Gibson’s cyberpunk paranoia and violating the sacred principle that every dollar spent must be lavishly displayed on screen. The Tribeca and Rockaway Film Festivals co-present the new cut’s premiere this Friday at a sold out outdoor screening. Earlier this week Screen Slate, which last year included Johnny Mnemonic in its screening series and publication 1995: The Year the Internet Broke, talked with Longo about his relationship to the much-maligned film and its ongoing “redemption.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

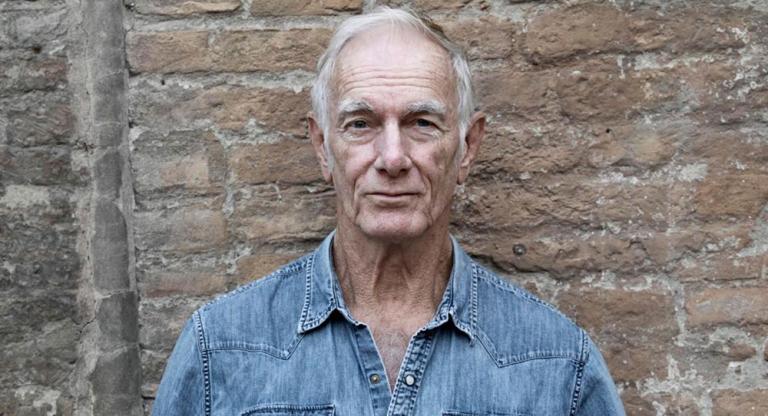

Patrick Dahl: I watched the black-and-white cut last night. It's really fantastic and I'm excited for other people to see it. What led you to consider doing this now?

Robert Longo: Well, I always had this fantasy that on the 25th anniversary I would try to get some redemption in relation to this film, because making it was really difficult. And I, at one point, thought about re-editing, but then I realized if I just turned it black-and-white that would be the best, easiest thing to do, and the most radical way of kind of imprinting how I really wanted it, because I wanted to make it in black-and-white originally. I wanted it to be like a contemporary version of Alphaville or something like that. Anyway, the movie, by dealing with Hollywood, had gotten out of control. Keanu had just blown up with Speed. Tristar wanted it to be their summer movie. It was kind of crazy. For me, for William, and for Keanu, this is a bit of redemption. They really love this new black-and-white conversion. And it looks like a shitty, million-dollar movie. It has a bit of a grunge to it and an attitude to it, which I think is really great.

Completely. The black-and-white knocks several million dollars off of the price tag.

Yes, it does, in a good way.

When I first heard about the black-and-white version, I thought about the color, which was one of the things that I really liked about the original. But when I saw the black-and-white version, I was like, "Oh, this feels so right." Because it has this kind of a dreamy, 16mm feel to it. It reminds me of Tetsuo and Eraserhead, and all these great, kind of dreamy, black-and-white movies.

Yeah, exactly. And I love all the video graphic stuff in black-and-white, it seems so great. In hindsight, the color graphics now look all pretty retro, but in black-and-white, it has its own quality to it for sure.

Without a doubt. It's a complete other world.

I think the three computer graphic sections become quite coherent in black-and-white as well, so I am very happy with it.

Is this the end of the line for Johnny Mnemonic? You mentioned redemption... are you still interested in re-cutting—

No. I have a day job. Originally, making this movie was a torturous experience. Dealing with the Hollywood people was difficult. First of all, they couldn't say “mnemonic.” They wanted to change the title to Johnny Gets His Gun, or some shit like that. And then, when Keanu blew up with Speed, they got really excited about it. And meanwhile, their summer movie that was supposed to be released, which was called Mary Reilly, was in a disastrous state and they couldn't release it. So, they thought, "Well, let's make Johnny the summer release."

Originally, it was supposed to be a February release. Instead, Johnny Mnemonic opened the same month as Die Hard [with a Vengeance] and Batman [Forever], but it did pretty well in the beginning. It was number four for a while. And then it got trashed by the critics, and I completely understand it, because the Hollywood people just messed with it so much. They tried to pump more money into it because they were making it their summer movie, and they were complete idiots. It was a difficult time, because the guy that was editing the film with me was Ron Sanders, Cronenberg's editor. It had a very different pace to it. And then the studio brought in another editor, and he didn't get it at all. It was a difficult situation. I mean, I'd say half the movie is what I want.

The DP that wanted to shoot the movie for me was a guy named Michael Chapman, who was Scorsese's DP. But the problem was that I couldn't have him do the movie because he wasn't Canadian, because we're shooting the movie in Canada. So, all of a sudden, our DP went from Michael Chapman to some Canadian DP. And the Canadian pool of DPs was quite weak. The one guy I really wanted to do it couldn't do it, and the guy I ended up with was a French guy who at least knew who Godard was. But, I mean, his major film credit was Weekend at Bernie's, so it was really difficult.

When you were making it, did you think about potential connections to the fine art world? Or, did you see it as compartmentalized from your work there?

One of the reactions in the movie world was, "How dare an artist try to make a movie." And then, in the art world it was, "How dare an artist try to make a commercial movie." So, I got fucked either way, in that sense. There was already a prejudice against it. Originally, my art emerged from a generation that was involved in appropriation. And I always thought it'd be really great to make a movie and steal my own images. That was one of the ideas. There's a lot of “stolen” art in the film. The dolphin is a reference to Damien Hirst, the big tower of TVs is a reference to Nam June Paik. I mean, there's a lot of art shit that I stole in it, for sure.

After it came out, was the art world any kinder, or did they remain skeptical?

I basically got thrown into the garbage heap for a while. My career tanked after that, for sure. Basically, I had to redo the 90s. I kind of missed the 90s in a weird way. It was a difficult period of time for me, for sure. I don't want to blame it on the movie, but the movie set me back quite a way. My wife at the time, Barbara Sukowa, who plays Anna Kalmann, said, "Why don't you just go back to the studio and draw?" I went back to the studio. I had no more assistants. I was kind of broke. And, also, my youngest son was born the first night of shooting in Toronto. After the film, I made a drawing a day for — it was a leap year, so 366 days — a project called “Magellan,” which turned out to become my lexicon of everything I've done since then. The hardest thing as an artist, as you get older, is to figure out how to stay relevant. I think I'm doing okay with my job right now. I consider making my drawings and sculpture in my studio to be comparable to making one gigantic film.

Oh, interesting. Would you mind elaborating?

The way I make my work is almost like a director making a film. I have different people working on different things. It’s very much like a film set in my studio. When [my friend, artist] Rashid Johnson was getting ready to make his film Native Son, he came to me asking for advice, and the best piece of advice I could give him is that you should shoot the most important part of each scene first, and get that done. And then you can get all the great visual stuff later on. I always wanted to make all these visual decisions, but I never had time. For the overhead scene in the bathroom, for example, I had to fight tooth-and-nail to get that scene done. It was tough in Hollywood. You have to remember: to them, ‘art’ is a boy's name, and they’re terrified of it. They're terrified of it, because they don't understand it at all.

You said, and I think you've said this consistently in the past, that you conceived the film in black-and-white. How long did that dream last? I imagine the studio wasn't even going to consider it.

Yeah. Well, there you go. You said it yourself. The evolution of the movie went through so many people. They had already planned in the very beginning to take me off the movie. I mean, the second unit director was promised the movie after the first week of the movie.

Oh, that's ugly.

It was a pretty fucking ugly thing. So, the second unit guy who was supposed to shoot all the action and shit, did a really shitty job. In the beginning, we were trying to raise a couple million dollars, and then I couldn't raise it. I couldn't get it together. And, in hindsight, I probably should have used my own money. I mean, that's one of the most brilliant things that Schnabel did with Basquiat. I was living in Paris at the time, and I met this guy in a bar who was an American art collector who was also a film producer, Staffan Ahrenberg. He wanted to work with me and now we’re very close. He and Peter Hoffman were executive producers. Staffan was the good guy, trying to help me make the movie I wanted to make. Peter was the bad guy, who tried to steer the movie in a completely cliché direction.

I'm assuming you try to limit contact with the studio nowadays, but do you have any sense of how they feel about the black-and-white cut?

Originally, when I decided to make this black-and-white conversion, I ripped a Blu-ray and turned it black-and-white. I contacted one of the film’s original producers who was also a good guy, Don Carmody. I said to him, "I'm doing this, and I'm going to dump it on the 25th anniversary. I'm going to dump it on YouTube,” or something like that. And he said, "Wait, let me see it." So, I sent it to him, and he got really excited. "This is really great. We should show this to Sony." I hesitated to get Sony involved at first, but the problem with the Blu-ray version is that the quality would not be good enough to project it in a theater. So, Sony gave us the footage to work from, and they may release this new version on Blu-ray There's never been a director's cut. Ironically, there is a version that some people misunderstand to be a “director's cut,” the Japanese version of it, but it's not a director's cut. It's basically got more Takeshi Kitano in it. That's basically what it is.

So, I got the hi-res footage from the studio, and we graded it into black-and-white. I worked with Cyrus Stowe, who was the colorist on this version. Basically, we went through it scene-by-scene, and he was really great. He's really a very talented guy.

Was that feeling of redemption there, throughout the process?

When I saw the first version of the black-and-white film, I was just so happy. It was so much closer to what I imagined it to be, for sure. I knew turning it black-and-white would get it closer to where I imagined it from the very beginning. In my work, I take inspiration from films like Alphaville, La Jetée, things like that. A lot of black-and-white movies are not really black-and-white. They're kind of gray. The contrast is really pumped up now [in this cut] so it’s very black-and-white.

In a lot of the interiors of the color version, there's kind of a smoke machine effect. It's a very hazy movie. And I think the black-and-white sharpens certain visual elements of it, while also giving it this dreamy vibe, which is really neat. Do you see a future in filmmaking at this scale?

Well, I've made a bunch of small arty films that I'm very happy with. I showed one in my gallery last year called Icarus Rising. Making a narrative film is really tough because you have to have a really great script. The problem with our script for Johnny Mnemonic was, the script was fucked with so much. The first couple of drafts were so great, but it was just so fucked-with. And here are these people telling Gibson how to write.

One of my greatest experiences on the film, and one of the production’s greatest outcomes was Johnny’s tirade on the mound under the bridge. William, Keanu, and I became really close friends. Keanu was basically the godfather of my youngest son because he was there when the baby was born, and we're still very close. Anyway, as I’ve explained, we were getting so frustrated with this whole movie. So I decided that the protagonist of the film should be really fucking frustrated. We're shooting in Montreal, underneath this bridge. And I said, "I got this great idea. I want to build a mound like it's the curve of the Earth. We can see the city in the background. And I want Johnny to flip out. I want him to flip out and say, “What the fuck is going on?” William wrote it that night and we gave it to Keanu, and it was my favorite scene in the whole movie, when he screams about how he wants room service. It was so great.

Yeah. That is my favorite scene as well. I have many scenes that I love dearly in the movie, but that is, by far, my favorite and —

That was never in the script.

When people talk about Johnny Mnemonic as a bad movie, they always point to that scene. And it just makes no sense to me. It’s a perfect encapsulation of that kind of frustration in a late capitalist society, and all its needs and desires, it's very post-apocalyptic, and it's so well-written... I don't know. It's a head-scratcher, but I feel the tide is turning on people's appraisal of the movie. So, I hope that continues.

Well, it's been pretty wild. William's been talking about it, too. It's kind of great that people are starting to see the movie that was in the movie. Do you know what I mean? It took a pandemic to change people's minds. It took a crazy-ass president. It was all sorts of things.

Special thanks to Alex Baye