What stands out almost immediately about Julie Dash’s 34-minute film Illusions (1982) is that it is completely sincere in its conflicting modes of loving Hollywood cinema and still detesting everything that the industry stands for. That’s not to say the movie doesn’t have a sense of humor, because it definitely does — a very dry one — but it also doesn’t cloak its criticisms of the film industry in a guileful, layered sense of irony the way that Altman’s The Player does. Dash can’t afford to do this, because her message is one that is much more personal and intimate and not abstractly structural.

The central character of Illusions, Mignon Dupree, a Black studio executive who passes for white, has the same grand visions and sentimental disposition towards movies and stardom as anyone who dreams of making a living in ‘the biz.’ But these illusions deteriorate amid the hidden conservative design of this magical industry, and it becomes hard to maneuver the web unless you are the spider. As a light-skinned woman, Dupree is a cipher for the racial conflict of Hollywood’s version of progressivism – a progressivism that serves to fancy the self-congratulatory nature of the white liberal elite. This was a prescient foreshadowing of the 90s rise of Will Smith and Denzel Washington, who were considered by studio heads to be appealing enough to white 20-somethings that they could be trusted to lead major star-vehicles like Independence Day and Crimson Tide.

Dupree, like Will and Denzel, is Black, but non-threatening to the white studio establishment, and Lonnette McKee’s performance nails the conflict inherent in this racial dynamic. She serves quite literally in the narrative as the go-between in the communication of her white traditionalist boss and a young rising Black singer named Esther Jeeter (Rosanne Katon) who is hired to sing voice-over for young white actresses. In a meeting between them, Dupree sees Esther as someone who is treading the same path she once did, but without the benefits of having a disposition that fits in the acceptable mold of white liberals. After the meeting, the secretary – an older white woman – tells Dupree, “darling, you certainly are good with them. I hardly know what to say to ‘em.”

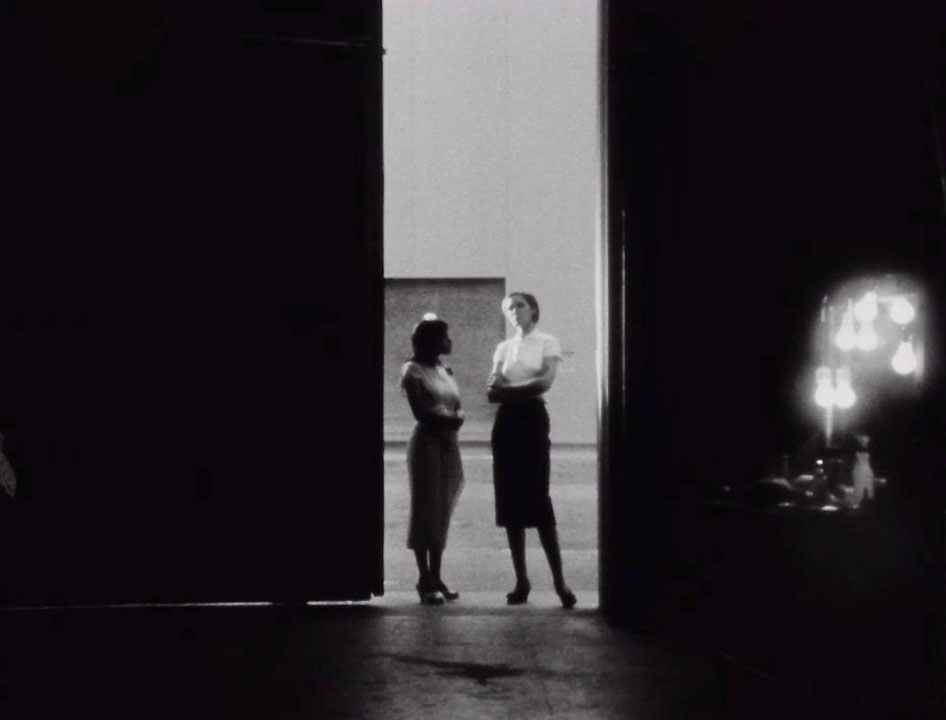

Dash consciously punctuates the film’s racial dichotomies with brilliant visual communications of the hierarchical structures. A static shot at the doorway of a studio set, Esther – darker and smaller – looks up at Dupree who has been successfully assimilated into Hollywood culture, both in the way she looks and the way she acts. Another sequence, more visually surreal, shows the recording studio with the disjointed visages of Esther, the sound designer, and a screen displaying the movie being voiced over. These are the simple ingredients of the Hollywood illusion – the devious hiding of Black talent behind the presentation of white stardom through the mechanisms of sounds and edits.

Dash’s movie is a masterpiece which perfectly blends a clear understanding of Hollywood’s political line-treading with a keen artist’s eye for how visuals intimately work with narrative to create a profound effect. One would consider a movie like this to be a bare minimum inclusion in the curriculum of USC’s or NYU’s prestigious pipeline film production schools, but even today it may seem a bit too radical and real in its bare-faced honesty about Hollywood liberalism. Why sour the rose-tinted eyes of the next crop of moths to the Hollywood flame?

Illusions is available to watch on Kanopy.