To think on the Middle Ages is to summon the unreal. As Western Europe fell into economic and cultural ruin following the collapse of the Roman Empire, its tenebrous afterglow would be defined by soaring myths. Unicorns. Dragons. Catholicism. Chivalry. Divine Mandates. The Knights of the Round Table. These larger-than-life creatures and causes all summon supreme composure in the face of the unknown. Considering this fantastical fugue in the history of Western civilization, the filmmakers Seth Price and Robert Bresson conceived of two wildly inventive interrogations of the weight conferred upon the legends of the Dark Ages.

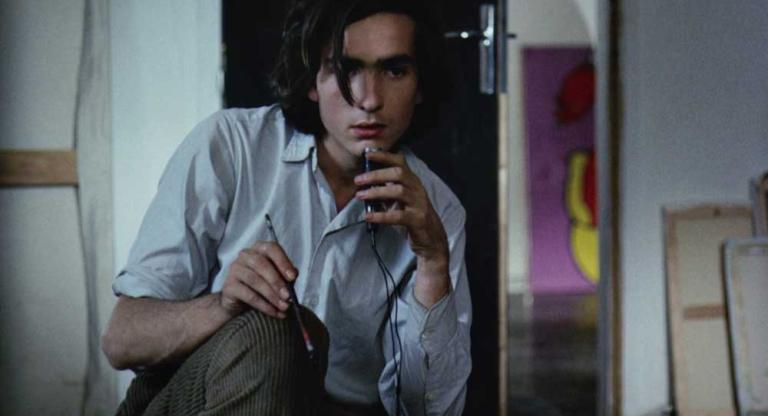

Paired in a double billing at Light Industry, Price’s Romance (2003) and Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac (1974) wield their anomalous formalism to question the inanity behind troubadour Chrétien de Troyes’s Arthurian Romances. The former, a thirty-minute stream of slime-green text, tracks Price’s progress through the proto-Zork computer game Adventure. Lacking images and sound, Price’s ascetic video-game walkthrough presents a tortuous quest littered with dead ends, his silent communion with his computer somewhat far from the epic promised by the game’s title. Not only does the rudimentary computer programming on display mark Price with death for each of his grammatically incorrect commands, but his repeated encounters with fantastic creatures—an axe-throwing dwarf, a serpent guarding a passageway—are set in a world of frustration, wherein higher powers submit an individual to a life with many ends.

Such is the setting of Bresson’s disemboweled Medieval tale. In it, Lancelot is neither cowardly or courageous; rather, he conveniently swings between both extremes. He murders in cold blood but also kills for love. All of the knights do; it’s the nature of their trade. According to Bresson, their downfall is not the moral treachery of their adulterous leader Lancelot—as legend so often has it—but an insidious corruption among the holy soldiers. “You were all relentless. You killed, plundered, burned. Then you turned on each other, like mad men, without realizing it,” Queen Guinevere says. In his condemnation of chivalry Bresson communicates a deep distrust of Western civilization’s ancient codes of honor, a misgiving that would evolve into a cynical critique of the world’s damned state in his last two films: The Devil Probably (1977) and L’Argent (1983). Far from romance, stripped of fancy, Lancelot du Lac is a solemn film disclosing a broken world, which turns to myth as a palliative from its constant misery.

Lancelot du Lac and Romance screen tonight at Light Industry.