There is a touch of eeriness in all of Sandra Lahire's films, an allure rising and falling like a tide, often lingering long after the watching is over. Water might have been her element, although not always in a liquid state—rather as shapeshifting matter that infiltrates her filmic compositions and morphs into different sensorial spheres, like a pulse becoming waves in a seashell. Channeling both benign and sinister feelings, water-related landscapes connect the many formal and conceptual layers that make up Lahire's small yet significant body of work. The British filmmaker made ten short-length films (nine under 30 minutes) from 1984 until her death in 2001, eight of which are now the subject of a month-long online retrospective on Another Screen. Shot in 16mm and bearing a strong component of materiality, the chosen shorts should ideally be projected in a cinema. Yet to stream them in chronological order does not diminish Lahire's vision, and indeed reaffirms the present-day relevance of her concerns while outlining the role each piece played in shaping the arc of her career.

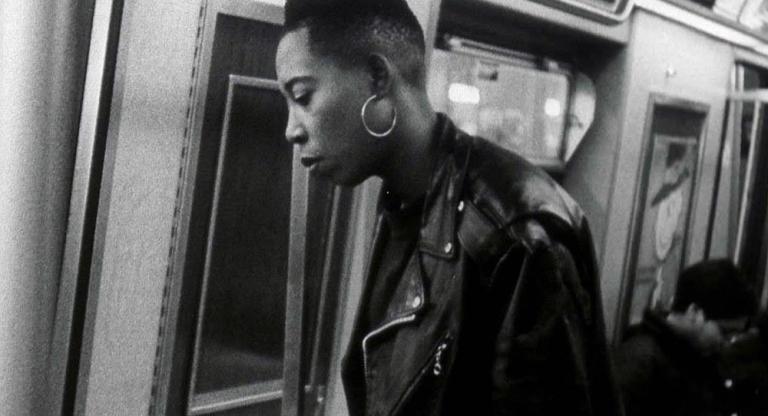

Born in 1950, Lahire was a principal figure in London's experimental film scene in the 1980s and 1990s. She studied film and environmental media at St. Martins and the Royal College of Art with Malcolm Le Grice, Lis Rhodes, and Tina Keane, and went on to work at the legendary London Film-Makers’ Co-operative alongside such filmmakers as Jean Matthee and Anna Thew. Benefiting from, and helping to inspire, the artistic fervor of that era, her work offers a crucial contribution to feminist cinema for the unique and sometimes literal ways it overlays formal experimentation, the filmmaker's subjectivity, and sociopolitical critique. Lesbian, Jewish, a militant feminist, and a Sylvia Plath scholar, Sandra Lahire worked to construct a film practice as a skin, the point of exposure between the artist's body and society at large. Her aesthetic manipulation of the filmic material paralleled the environmental transformations propelled by techno-patriarchal culture.

Alongside the various images of water (often shown in foamy, stormy, or otherwise tumultuous states, and heard in soundscapes, dripping or cracking as ice), birds are a recurring presence in Lahire's oeuvre. Owls, seagulls, ordinary city birds—all draw a continuous line between the eco-feminist core of her filmmaking (explored by Terminals in 1986 and by the subsequent “radiation trilogy”) and the theme of anorexia (Lahire's lifelong struggle that caused her premature death). In her first film, Arrows (1984), birds are seen displaying their structural frailty, or caged, flapping strenuously to break free. At times the filmmaker enters the frame, introducing the intercutting self-portraiture that will recur in later works, revealing her naked body, often in front of a mirror and holding a camera. In Arrows, which includes live-action as well as animated scenes, she is seen moving her elbows up and down, mimicking the birds' wing movement, but without the same vigor. Sylvia Plath interjects in voiceover, reading her poem “The Thin People,” which envisions figures “Meager of dimension as the gray people / On a movie-screen. They / Are unreal, we say.” Not only an elegy to the victims of the Holocaust, the speech also establishes an indirect dialogue with the viewers as they observe the filmmaker's body captured on screen.

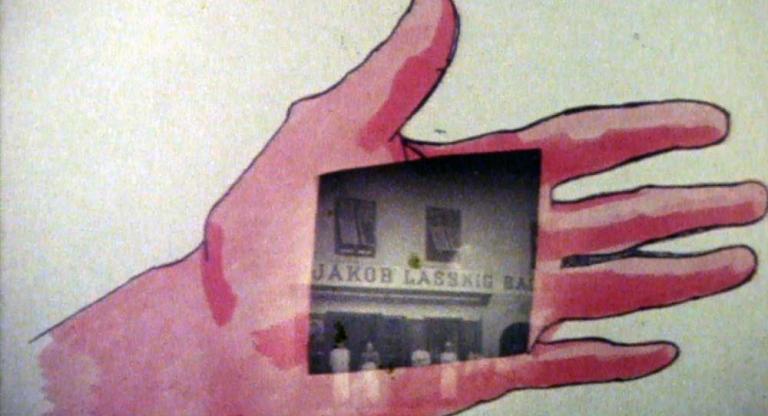

Plath's legacy is at the center of Lahire's second and final trilogy, Living on Air, and was also the subject of the doctoral research she started in 1999 under the supervision of feminist scholar Jacqueline Rose. While the last installment of this triptych (Night Dances, 1995) unfolds as an open investigation of Lahire's Jewish origins, this quest is anticipated by the apparition of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg in Lady Lazarus (1991), the first film Lahire explicitly devoted to Plath. A biopic in the style of artists’ moving image—somewhat along the lines of Isaac Julien's Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1995), but on a lower budget—Lady Lazarus stages episodes of Plath's life as told by a number of her texts. Using tableaux as narrative pivots (e.g., a Ouija board to summon the dead poet's memories, a snow-globe to introduce her first trip to New York, a pink Cadillac as an emblem of suburban lifestyle, etc.), the film intersperses photographs of Plath with the filmic layering peculiar to Lahire's formal experimentation. In the first scenes, the poet's handwriting and the printed text of the poems “Axes” and “The Sap” appear superimposed like wounds or scars on the filmic surface.

“I couldn't help wondering what it would be like, being burned alive all along your nerves.” Lady Lazarus quotes a passage from The Bell Jar about the 1953 electrocution of the Rosenbergs. This sentence sticks out like a knot in Lahire's historical view: if the Shoah and fascism shook human existence in the past, the present is threatened by the exploitation of the landscape, specifically by nuclear power. Terminals (1986) and the radiation trilogy—Plutonium Blond (1987), Uranium Hex (1988), and Serpent River (1989)—explore the philosophical and social implications of exposing living beings to radioactive matter. Shooting in Ontario, between Elliot Lake and Serpent River, Lahire interviewed exclusively female laborers employed as uranium miners or nuclear power station operators. The women's dry summaries of their working conditions (by which they were exposed to the risk of lung cancer, miscarriage, and neurological impairments) and of the environmental damage around them is contrasted by time-lapsed impressions of crisis situations and control, a throbbing visual commentary of glowing electronic interfaces, helicopters, and cyclone fences. Footage of male miners descending into the depths or drilling into the rocks flashes by in syncopated edits and colorized sequences, as if the radiation had exposed the celluloid itself. In Serpent River, the black-and-white X-ray scans of a potentially sick laborer’s chest are paired with images of Lahire's naked back as it bends and twists, with bright red marks highlighting the protrusion of her bones. Haunting yet empathetic, the symbiosis enacted by the artist looks like an act of both compassion and self-destruction.

Writing in 1985 about lesbian representation in media education, Lahire observes that “for women filming women, what we need now is to restore the integrity of the whole body.” By employing her corporeal presence in the same register as the filmic matter itself, Lahire presents her personal experience as a crucial point in the dialectic between abstract artistic vision and the society challenging such vision. “In the case of women dealing with autobiographical material and self-perception, turning the camera on herself is necessary,” she writes. “She [the woman] opposes externally imposed images of her sexuality by building a dialogue with aspects of herself.” Seen from within the queer perspective that frames this realization, Lahire's cinema is far from a solipsistic exercise, and instead argues for a “self-reflection essential for self-determination and political change” that remains a key lesson for how to look at the world.

“A Moving X-Ray: Seven Films by Sandra Lahire” streams through June 15 on Another Screen.