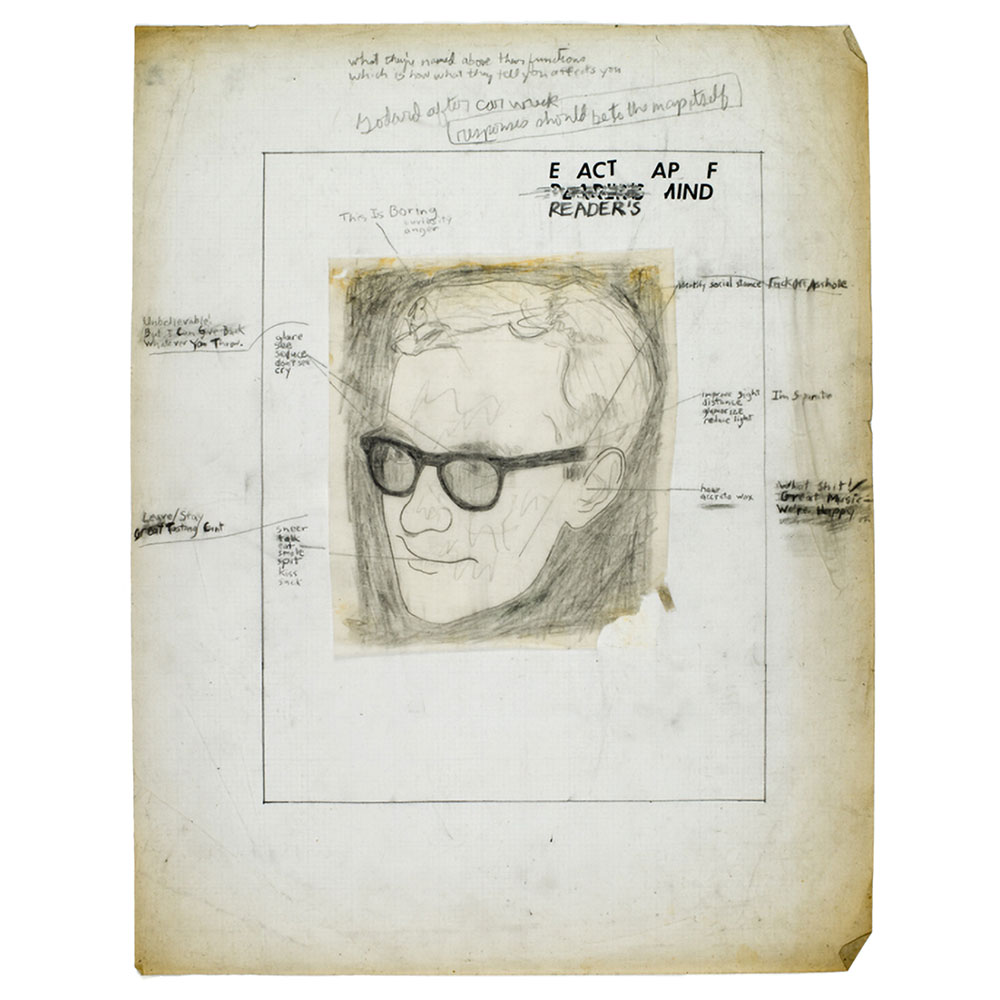

Sketch by the author circa 1977-78.

First, I’m sad about his death. It feels like the death of a parent. And one whose every move I craved to know, and loved, though he was 91. He was still the one to learn from.

That’s what I’m going to try to write about: what I feel I’ve learned from him.

The first thing I remember gleaning was that it was possible to make glamorous art that was intellectual. Godard, of course, was the most glamorous of filmmakers, as well as the most intellectual, the one most prone to study, to analyze, and to allude to his sources. So, are you maybe skeptical of my use of glamorous as an attribute of interesting art? How about charismatic? What are those two words really about? Glamour is an “early 18th century (originally Scots in the sense ‘enchantment, magic’): alteration of grammar. Although grammar itself was not used in this sense, the Latin word grammatica (from which it derives) was often used in the Middle Ages to mean ‘scholarship, learning,’ including the occult practices popularly associated with learning.” (Oxford English Dictionary) So, glamour and intellectuality are actually the same thing, and they are magical. In America, the model of the artist is more the noble savage type, suspicious of “book learning,” and this is what I grew up on—that an artist should be a cowboy (Jackson Pollock, Bob Dylan, even Andy Warhol). It was liberating to see a great artist who was proud to think. Charisma is grace. It is a quality that has no explanation except that it is divine. Charis (Greek: grace) was one of the names recorded for an attendant, one of the three, to Aphrodite, goddess of beauty. In the 17th century, charismatic came to mean possessing a gift of healing and for teaching. Are you really bored now, reader? Blame it on Jean-Luc.

That’s another lesson: that it’s OK to be boring. Do not fear to bore. A filmmaker like Tarantino fears to bore, which is one reason why he’ll never be as interesting as Godard, whose film title Bande à part he (QT) borrowed for his first production company (A Band Apart). (Which isn’t to say I can, or want to, resist Tarantino’s movies.) Artists’ boring sides are sometimes their most characteristic and indispensable. (One of the seven books of In Search of Lost Time is 500 excruciatingly boring pages of obsessive jealousy, but Proust is Proust and you can’t have it any other way. Moby-Dick spends endless paragraphs on conjectures that are now painfully worthless, about the science of whales. Andy Warhol.) But this is a digression. Godard is willing to do something in a movie just to see what happens if he tries it. He can be boring in the exercise of his full freedom, but you can’t have one without the other, and I want them like nothing else.

Which is another of JLG’s achievements and lessons: the revelation of the inextricability of opposites, of dualities. Richard Brody’s mostly adoring biography of Godard convincingly describes a near-invisibly pale shadow of antisemitism in the filmmaker—basically the capacity to revert under pressure to some language of stereotypes—except that to a conscientious biographer nothing is negligible, and I respect that (a little). In a way, the definition of film is the image that results, in the viewer’s mind, from the clash of two images, or in the space between them. This magical result is the reconciliation, or transcendence, of opposed or separate realities. One of my favorite and one of the seemingly most heartfelt of Godard’s movies is his late Notre Musique (2004), which is perhaps the fullest flowering of his dialectical mentality, and which is about Jews and the problem of Israel oppressing Palestine, or about filmmaking, whatever you want to call it.

Is Israel the opposite of Palestine? They are so similar! That’s not exactly what the movie is about, though. It’s about hell and heaven, and especially about the huge space between them, known as purgatory. The film has three sections: ten minutes of hell at the beginning, ten of heaven at the end, and 59 minutes of complex, emotional, beautiful, horrifying, and intelligent purgatory in between. That’s the structure Godard created, with a nod to Dante, to try to examine the situation in the Middle East, or the possibility of holding opposing stances at the same time. Set in the ruins of Sarajevo. Massacres upon massacres, in wrenching confusion and searching investigation, approaching reality.

Yes, there’s not much that’s light-hearted in that film—though Godard maintains wit and slapstick too almost everywhere he goes, or at least that embracing of opposites. In fact, the opening hell section of Notre Musique, with its relentless montage of documentary war footage mixed with the violence perpetrated in commercial westerns and war films, had the curious effect, for me, of being almost soothing in its rapid, graceful motion and continuous efflorescence, almost as if it could be time-lapse photography of flowers blooming: seductive, even invigorating, in a kind of dreamy, stoical way. It felt good to consider from the vantage of a movie audience the moving, lyrical, continuous, and boundless viciousness of people towards each other. And Godard provoked these thoughts in a viewer by means of his neutral juxtaposition of imagery. He didn’t state or suggest any of these reactions I describe—he just showed images. He made you consider what humans are, how they are constructed and behave. The movie is about the mutual dependence of certain dualities (which is “our music,” the music of the human state): death/life, darkness/light, negative/positive, documentary/fiction, criminal/victim, shot/reverse shot. Those are the things he considers in the movie and incidentally reveals as separate faces of the truth. You do not find this kind of revelation stimulated by very many films.

But maybe the most important thing I’ve gotten from Godard was a widening of my understanding of what in the artist’s life and consciousness is suitable for use in his or her work. This is another aspect of him that is unmatched by other filmmakers, but that he shares with the greatest artists throughout history—in fiction, for instance: Cervantes, Sterne, Melville, Woolf. They all introduced in their work personal and intellectual considerations and impulses that prior to them were not thought appropriate to the medium (if the medium existed; in a sense, each invented his or her medium anew). Godard is the king of this in film. The only thing consistent about what goes on in his movies is that the phenomena originated in his life and thought. This is a wonderful thing to learn from an artist in one’s own time: that the object is to reflect and consider life, and the only access you have is your own being and perceptions, so if you want truth, don’t exclude anything. That’s how it felt to me, anyway. Goodbye to language.

Richard Hell’s Destiny Street Complete double CD, along with LP versions of Destiny Street Remixed and Destiny Street Demos were released in 2021. His pamphlet “Chronicle" also came out last year, and will be included along with an essay and about 40 new poems in What Just Happened due in the spring of 2023.