Over the weekend of March 10–12, 1972, as many as 10,000 people convened in Gary, Indiana, for the first National Black Political Convention. In a high school gymnasium, under the pennants of the West Side Cougars, a who's who of Black leadership took the stage. Betty Shabazz introduced Jesse Jackson. Jackson introduced Bobby Seale. Queen Mother Moore made the case for reparations in the corridor between sessions. Amiri Baraka, one of three convention co-chairs, acted as the moderator for the plenary. (Notably absent was Shirley Chishholm, who foresaw that her presidential candidacy would fail to secure the support of the male leadership at the convention.)

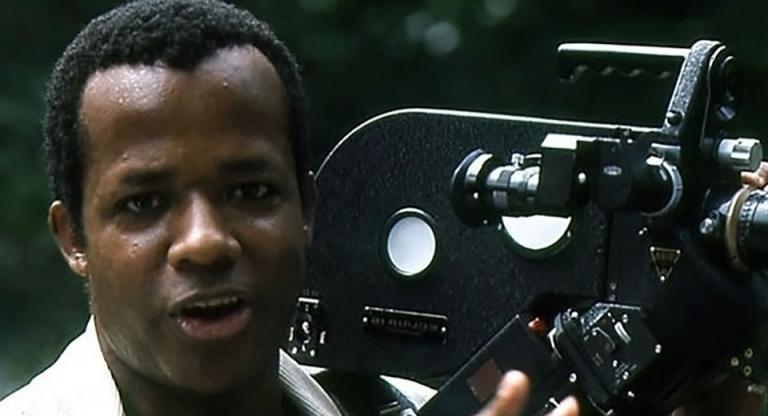

It was Baraka who had thought to invite William Greaves to document the event. Greaves is now best known for Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968), his triply-nested meta-documentary masterwork. That film went largely unrecognized until 2006, when it finally received distribution. In 1972, Greaves was coming off an award-winning tenure as the producer of WNET's Black Journal, teaching at the Lee Strasberg Institute, and making documentaries independently and on commission. He arrived in Gary with a small crew, enamored as anyone in attendance with the convention's historic potential. Throughout the film, Sidney Poitier reads Greaves's narration and Harry Belafonte recites Baraka's poetry, both articulating the profound ambitions attached to this moment.

Nationtime finds the Black liberation movement at a crossroads. Seven years had passed since Malcolm X's assassination, four since King's, three since Hampton's. One year prior, activists had burgled an FBI office in Media, PA, turning up the first concrete evidence of COINTELPRO's infiltration and sabotage of Black and New Left organizations. The passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts had formally conferred the full benefits of citizenship onto Black people, but for many the material conditions of life had not improved. As Johnson’s War on Poverty programs dried up under Nixon’s policy of “benign neglect,” they may even have been growing worse. As Jesse Jackson puts it, “We find ourselves with the right to move in any neighborhood in America, and we can’t pay the note.” His speech to the assembly is presented in full, and the film takes its title from his call-and-response refrain ("What time is it?"), which was borrowed in turn from Baraka.

Greaves's film is said to have been "too militant for television broadcast," and only a much-reduced 58-minute version has ever been in circulation. In 2018, the original cut was discovered in a Pittsburgh warehouse and restored under the supervision of Louise Greaves, the late director's widow and creative partner. Besides a significant improvement in image quality, the restoration includes 22 minutes of material that had been thought lost. A musical intermission includes a performance by Isaac Hayes. The comments of Dick Gregory, thin from his anti-war hunger strike, are given more screen time. Somewhat more of the actual business of the convention is featured, as well, giving insight as to the determination necessary in creating and maintaining consensus.

Perhaps what had been "too militant" for the censors were the remarks of Bobby Seale, of which only a brief excerpt appears in the previous edit. He attempts to make common cause with less radical members of the audience, proffering an expansive definition of the revolutionary and analogizing the vote to a loaded gun. After a split with Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther Party was in the process of shrinking its national operation and concentrating its efforts in the East Bay. Two weeks after the convention, the Panthers held a Black Community Survival Conference, where they distributed groceries, provided testing for sickle cell anemia, and registered thousands to vote.

The convention took up Baraka's calls for "unity without uniformity," bringing together integrationists and separatists, proponents of nonviolence and those participating in armed resistance, grassroots organizers and elected officials – including members of the recently-formed Congressional Black Caucus. The goal was to democratically draft and ratify a Black Political Agenda, a checklist of policy positions by which politicians could be held accountable to the Black people whose support they sought. Gary's mayor, Richard G. Hatcher, also a co-chair, threatened in his keynote address the possibility of violence and the creation of a new party if the convention's resolutions were not heeded: “Those of us already disenchanted with the political system could conceivably turn to other tactics, shattering the quiet routine of daily life in this country."

The Gary Declaration, as it was framed by the heads of each state delegation, decries “the twin foundations of white racism and white capitalism.” Demands for the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam and "the eradication of heroin in the ghetto" were met with thunderous approval from the outset. On the third day, the fault lines of the coalition began to show. As the full platform came up for a vote, a large part of the Michigan delegation walked off the floor. The episode is captured in the film, but its contours are mostly left blurry. Their objection was to two resolutions in particular. The first was in opposition to school busing. The second was a condemnation of Israel's "expansionist policy" and "forceful occupation" of Palestine. Later, there was some speculation that the Michigan walkout was the product of a directive from UAW, which may have sought to protect the union's relationship to the Democratic Party in that state.

Within weeks, hopes of a unified Black political program were sunk by moderate backlash. The NAACP withdrew its support of the National Black Agenda over the resolutions to which Michigan had objected, both of which had been retroactively softened since their ratification. This controversy occupied the interests of the press, often to the exclusion of much attention to the central planks of the agenda. These concerned such issues as nationalized healthcare, a guaranteed minimum income, free higher education, and Black community ownership of media networks. Soon the Congressional Black Caucus put aside the Agenda altogether and presented a far more mild "Black Bill of Rights" in its place.

In November, Nixon won reelection in a landslide. The following year, Seale lost his bid for Oakland’s mayoralty, and the Party soon began its ignominious descent in earnest. The National Black Political Convention was reiterated in Little Rock in 1974 and in Cincinnati in 1976, but attendance and enthusiasm fell off precipitously. Jackson ran for the Democratic presidential nomination twice, losing only narrowly in 1988. Baraka's avowed Black nationalism eventually became a call for socialist revolution.

Perhaps by some metrics, the turn to electoralism and reform yielded acceptable results. By 1980, the number of Black elected officials in the US had quadrupled. In 2008, the country finally elected its first Black president. But had representation come at the cost of deep concessions to the political establishment at a time when revolution seemed real and near?

Tellingly, the first scene of the film takes place in a side room where the press has been gathered. A spokesperson expresses concern that the large number of reporters in attendance not interfere with the convention, “particularly since there is so much media to witness how we take care of our business.” There is an awareness that the success of the convention will lie as much in the telling as the doing, and that some of its professional spectators may be obstacles.

The film itself refuses to accept the narrative of the convention as a failure. A new on-screen prologue maintains that while it "adjourned without reaching consensus," the event was "a turning point in the struggle for self-determination and equal rights." Here and elsewhere, the tragedy of what might have been is no more palpable than the promise of what might still come to be. This past August, in the midst of the largest protest movement in the nation’s history, the Movement for Black Lives hosted the 2020 Black National Convention, at which a new political agenda was ratified, including demands for reparations and prison abolition.

Nationtime is an essential document, charged with portent and embellished by Greaves's restless camera. Again and again, the frame is filled with indelible images of the occasion: Jackson biting his fingernail as he waits to speak; Seales's comrades replacing the leather jacket around his shoulders; Betty Shabazz and Coretta Scott King sharing a private word on the dais, their eyes full of loss and life.

Nationtime is streaming on the Criterion Channel or available to purchase/rent from Kino Now.