Though perhaps best known for his decades ahead-of-its-time docufiction hybrid Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (1968/2005), William Greaves's career as a filmmaker is much more expansive than that one work, stretching across six decades and encompassing over a hundred films that explored society, politics, and the Black experience in America. Like so many documentarians whose work screened largely in non-theatrical spaces, Greaves has a vast but largely inaccessible filmography, with only Symbio ever having been available on home video. Despite that lack of commercial visibility, Greaves's importance as a director and cultural figure cannot be overstated: through his films on African-American culture, his production of the groundbreaking WNET newsmagazine "Black Journal," and his mentorship and encouragement of directors like St. Claire Bourne, Horace Jenkins, Madeline Anderson, and Stanley Nelson (whose Firelight Media recently launched a fund in Greaves's name), it's arguable that Greaves did more than any other filmmaker to birth and develop a Black voice in film and television in midcentury America. Fortunately, three of his key early works can be found online, and taken together, they form a fascinating narrative about an artist seeking his calling and finding his voice both through and despite the structures available to him at the time.

Born and raised in Harlem, Greaves began his professional career as an actor in the mid-‘40s, appearing on stage with the American Negro Theater, studying at the Actor’s Studio, and starring in some of the last “race films” to be produced, as well as 1949’s passing drama Lost Boundaries, whose producer Louis de Rochemont (creator of the March of Time) let Greaves sit in on the editing process. Keen to move behind the camera, Greaves took filmmaking courses at City College and was deeply influenced by John Grierson’s view of documentary as a tool for education and political change, which aligned with his growing desire to explore Black life and history onscreen. Finding all doors shut to him in the U.S., Greaves – nearly a decade before Melvin Van Peebles went to Paris for the same reason – moved to Canada and pursued a gig with the Grierson-founded National Film Board, working his way up from negative cutter to a key player in the NFB’s documentary-focused Unit B.

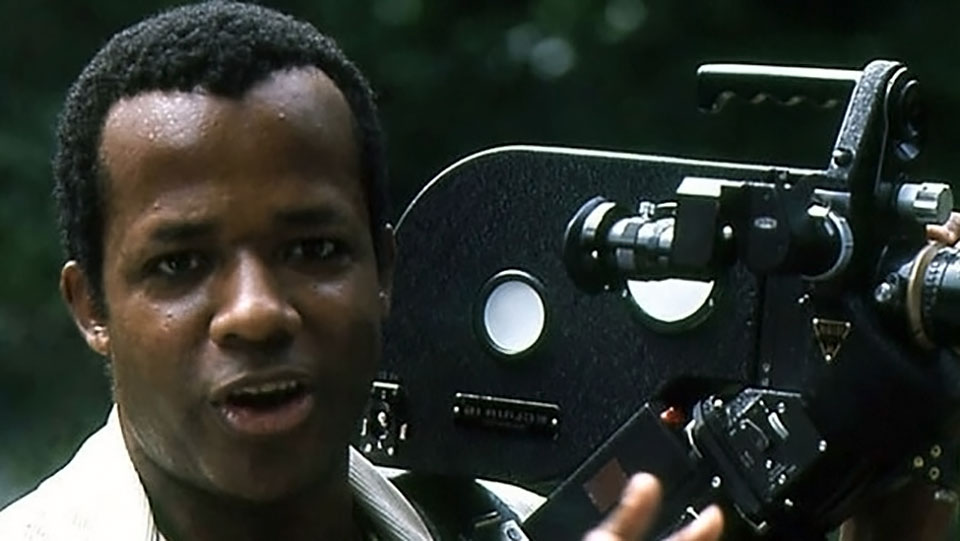

Made in 1958, Greaves's first NFB effort Emergency Ward is a fascinating work that reflects the transition in documentary from didacticism to Direct Cinema and its director’s clear glee at finally having a full toolbox. A half-hour portrait of the emergency ward at Montreal General Hospital, the film is driven by several tensions: between a calm narrator who reassures us of the staff’s “expert knowledge” and Greaves's urgent, off-camera voice asking them blunt questions about “mistakes”; between static shots of dull routine and handheld shots of frantic chaos; and between the faith in institutions urged by the film and the suffering and loneliness it depicts. Beautifully shot by Wolf Koenig and kinetically edited by Greaves, the film is an explosion of technique that boasts several unforgettable images and announces Greaves's arrival as a filmmaker – he even appears on camera at one point, leaning against a window while listening to an orderly’s rambling anecdotes. Nevertheless, one gets the sense that Greaves is itching for a freer form or more expansive subject, honing his craft while waiting to make the films he wanted to make.

That opportunity was not forthcoming at the NFB, and Greaves eventually returned to the U.S. to take a job as a director with the U.S. Information Agency’s Motion Picture and Television Service, whose head George Stevens, Jr. had seen Emergency Ward and was eager to diversify the department’s ranks. Working again under the auspices of a state-sponsored institution, Greaves made his first U.S.I.A. film, Wealth of a Nation , in 1964. Ostensibly a look at freedom in America, the film is an appropriately wild twenty-minute essay that encompasses profiles of sculptor Lee Bontecou and architects William Katavalos and Paolo Soleri, a live performance by trumpeter and composer Bill Dixon (who also did the film’s brilliant free jazz score), and an excerpt from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, all within a framework that presents the self-expression of everyday Americans as necessary to the health of the nation. A frantically edited work with a ponderous voiceover whose quick cuts of freeways, fighting children, and frugging at times suggest the future shock collages of Greaves's NFB colleague Arthur Lipsett, Wealth of Nation got Greaves closer to his goal of exploring Blackness on screen, but he wasn’t there yet.

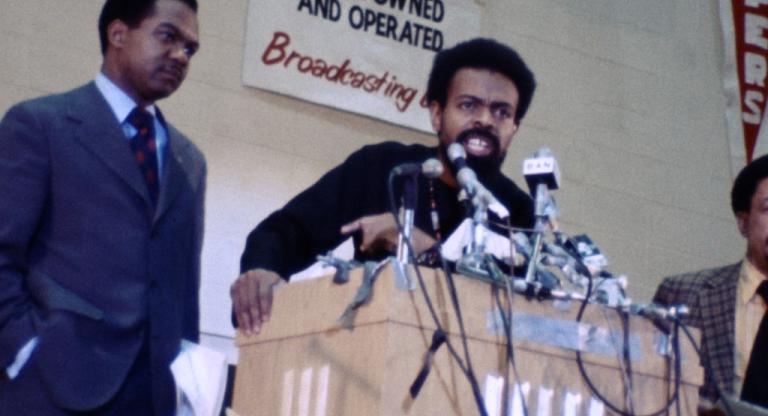

To get there, he had to go abroad yet again: to Dakar, where he was sent by the U.S.I.A. in 1966 to shoot footage of the World Festival of Negro Arts, a 24-day event organized by Léopold Senghor, the poet-philosopher and first president of Senegal who had led the country to independence in 1960. Senghor – whose formulation of Négritude in Paris in the 1930s had emphasized an affirmation of African culture and tradition, and whose work as a statesman embraced international exchange – worked with UNESCO to build a Pan-Africanist conference that gathered together artists, writers, musicians, and dancers from over 45 countries in the context of a continent rapidly achieving autonomy. Assigned to gather a few minutes of silent footage, Greaves realized the magnitude of what he was witnessing and improvised, imploring Stevens to send more stock, enlisting his driver to record audio, and piggybacking on lighting rigs set up by a Russian film crew. The end result, The First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966), was a landmark for Greaves, a paean to the richness of Black culture that that elides its production restrictions through skillful editing and complex aural montage. Gone is the voice-of-God narration of the previous films, replaced instead by a poetic, Langston Hughes-inspired voiceover that expresses a multitudinous identity; gone too are the attempts at explicit argumentation, in a film given over to awe at the art, sculpture, dance, and performance that it presents. And in choosing what art to highlight, the U.S.-backed Greaves shows no chauvinism, including Hughes, Ellington, and Ailey but focusing largely on representatives from the other countries in attendance: dance troupes from Liberia, Gabon, Mali; musicians from Trinidad, Togo, Brazil; the motorcade of Emperor Haile Selassie; a colloquium featuring Senghor and Aimé Césaire. Though like the festival, Greaves's documentary privileges cultural expression over political discussion, African independence and its implications for the American Civil Rights movement is implicit throughout the film, and its success enabled the filmmaker to directly address the political and cultural revolutions affecting Black America in his subsequent work, from 1968’s Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class to the recently restored Nationtime – Gary, a document of the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana. “The first opportunity I had to make films that expressed a Black perspective on reality,” The First World Festival of Negro Arts was Greaves's true breakthrough, and a work that paved the way for the triumphs to come.