True to its namesake, Lutz Dammbeck’s The Net (2003) excels at the hyperlink-style essay film format in which pulling the threads of seemingly disparate modern phenomena—avant-garde art, technology, armed conflict—reveals a single tight-knit system. It’s the documentary equivalent of Googling the Unabomber and falling into a virtual K-hole that bottoms out with a dozen browser tabs on Nam June Paik, animal husbandry, and MKULTRA.

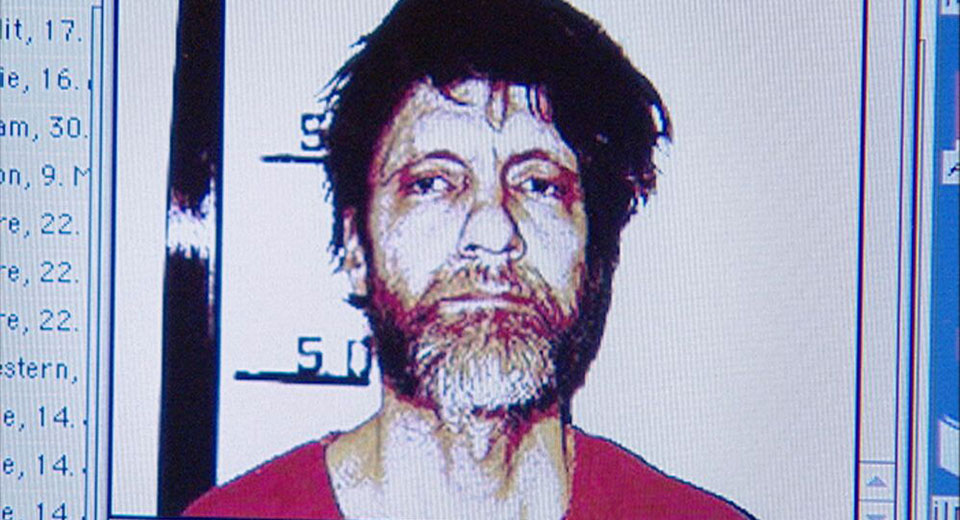

Doing a web search on the Unabomber is, effectively, the movie's point of departure. As Dammbeck becomes fascinated with Ted Kaczynski, he begins to dig deeper into his Neo-Luddite ideology and victims in academia and technology. His search brings him into contact with figures including Stewart Brand, editor of the self-sufficiency countercultural publication Whole Earth Catalog, and science/art literary agent John Brockman, who draws connections between Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics and avant-garde figures including John Cage, Jonas Mekas, and USCO. Gradually the narration begins to pull in Dammbeck’s own correspondence with the incarcerated Kaczynski.

The Net expertly sheds light on the social and personal networks underpinning our increasingly digitally mediated lives. Pitched at the turn of the millennium, with news of George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq playing out in real time in Dammbeck’s hotel room, it’s not merely a diagram of the lines and nodes that form a secret history of the newly departed 20th century, but a compelling and often unsettling examination of the morality of the architects of contemporary society. That Brockman has recently been widely publicized as the “intellectual enabler” and “superconnector” at the center of Jeffrey Epstein’s social climb adds a whole new dimension—and unsettling legitimacy—to Dammbeck’s probe into the power of networks.

The Net screens Saturday, May 11, presented by Other Cinema at Artists' Television Access.

Previously:

The Net screens September 7, 24, 27, and 30 in Spectacle's series The Spy Who Dosed Me